- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ukraine Revisited

- Article Subtitle: What steppe to take

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dmytro Chub, in his introduction to On the Fence: Ukrainian Prose in Australia, observes that ‘Although there are some fine novels set in Ukraine’s historical past and under Soviet rule, the period spent in Displaced Persons camps in Germany and the emigré experience in Australia has given birth to no more than a few short stories. While older writers sentimentalise about a lost past, younger writers do not wish to stir up the sensitive issues in the community.’ This is the problem of the anthology. While it may be admirable to translate into English Ukrainian writing, the act of doing so exposes the weaknesses of translator and writer. As long as the prose or fiction remains within the language context of the group, it gains from the common memory of things past, shared pain, shared loyalty, shared guilt. To the printed word is added associated experience. Set it into a new language, a different social context, and the word has to work much harder in getting things right.

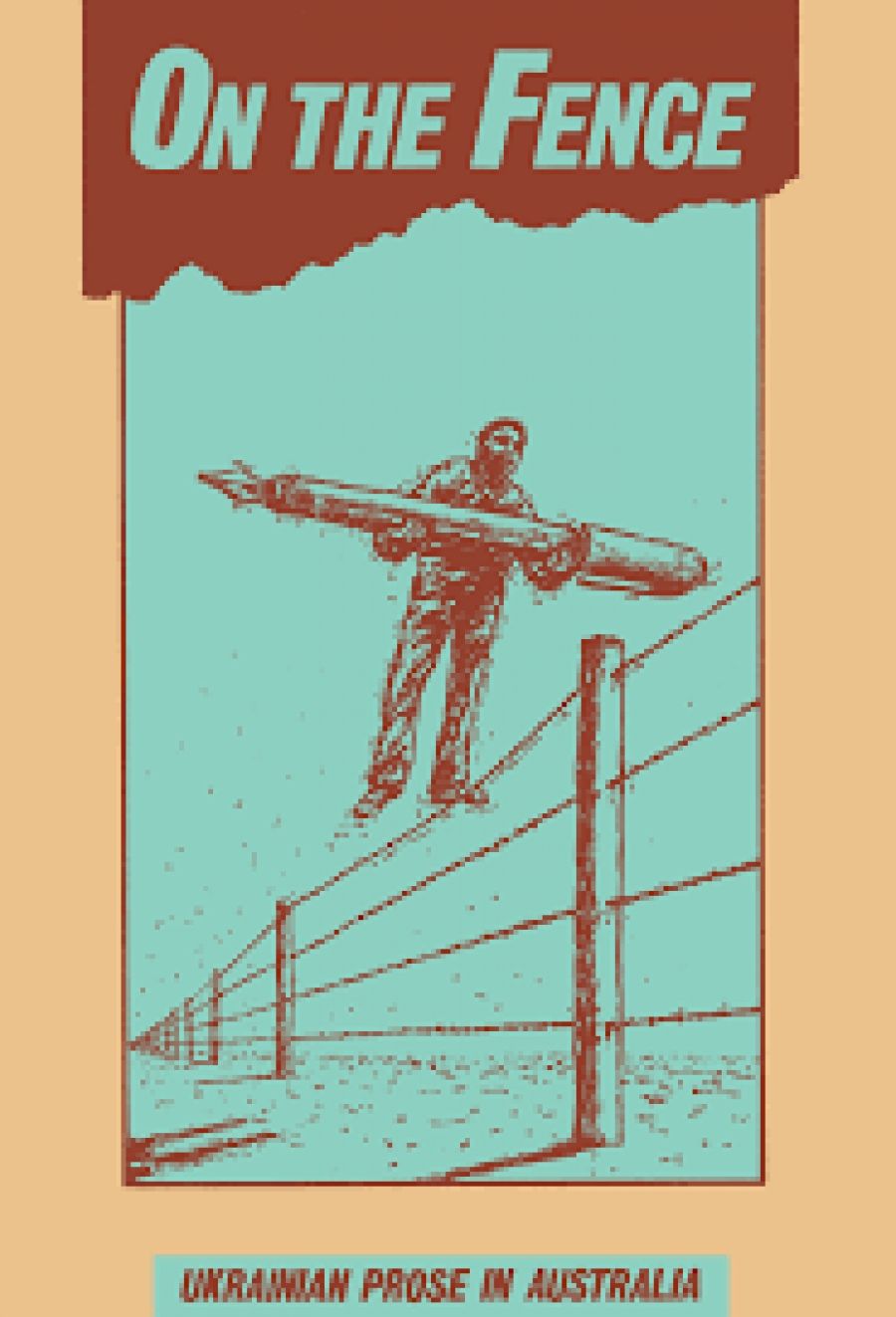

- Book 1 Title: On the Fence

- Book 1 Biblio: Lastivka Press. $6.95 pb, 152pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

One of the best pieces, ‘The Power of Beauty’, while relying strongly on the sense of a speaking voice, imaginatively parallels two moments of epiphany. The first is a painting by a Russian in which two Soviet soldiers are caught by the beauty of Raphael’s painting of the Madonna. ‘One of the soldiers is holding his helmet, removed as if out of respect; the other, wounded, seems frozen in mid-movement.’

Many see this as ‘“A typical made-toorder Soviet socialist painting! ... A blatant piece of propoganda!”’’. The protagonist then recounts his experience of the ‘ridiculous evacuation of Kiev’ and shows an actual moment of epiphany which he experienced. Amid the chaos, death and blasphemy there is a moment of illumination. ‘On the far side of the ditch, on a small mound, stood a naked young woman. … She was wringing the brassiere and panties she had removed, sending a stream of muddy water to the ground. She stood there unmoving, indifferent to her surroundings and the dozens of male eyes fixed on her. Facing the marsh, with tightly pursed lips, she stared with wide-open eyes in the direction of Kiev.’ I would have preferred the story to end without the over-explicit moral that even Russian soldiers are people. Yet, I’ve been taught to read symbolically, others haven’t had the privilege of my education or the benefit of cultural exposure which included symbolic interpretation.

Some of the stories are reworked folk-tales, others are reminiscences of personal history; painful to read because the horror, the confusion and hurt are so ineptly told. There are many stories which remain untold because guilt, fear, and total inability to confront what was done and to whom, prevent the emigré from telling. To have power over language to recount the heart of darkness, is something to wait for in Ukrainian writing in English.

Comments powered by CComment