- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The history of Australia at war has tended to focus on the exploits of the Australian army to the neglect of the other two services. It is usually forgotten, for example, that the most famous of Australia’s military actions, that at Gallipoli, was part of a combined operation, in which the failure to land the troops at the designated spot virtually condemned the attack from the outset. In both world wars, command of the sea was the prerequisite for Australia’s military participation and for her own security. Far removed from the main theatres in World War I, Australian forces had to be transported thousands of miles by sea to the Middle East, Gallipoli and the western front. Allied sea power made that possible.

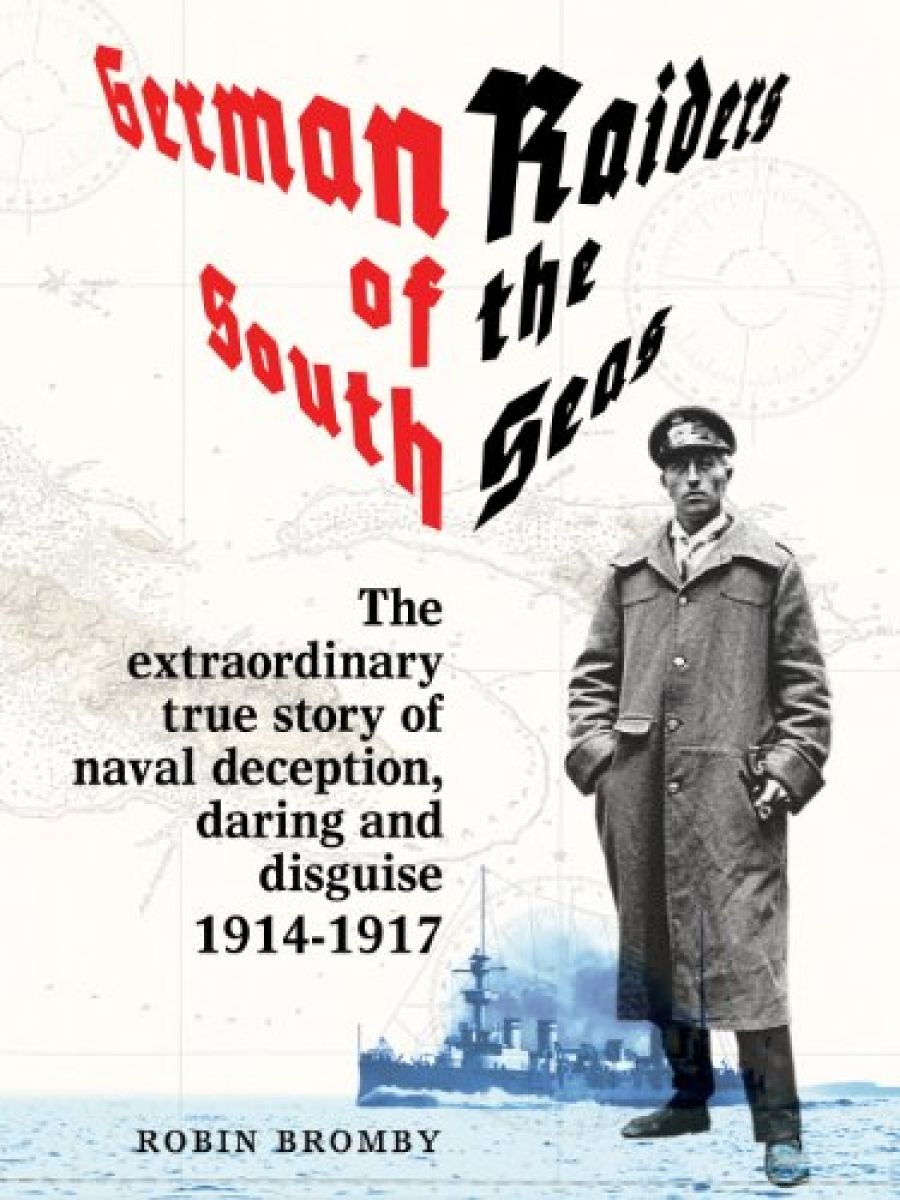

- Book 1 Title: German Raiders of the South Seas

- Book 1 Biblio: Doubleday, 208pp, $19.95pb

- Book 2 Title: Royal Australian Navy 1942–1945

- Book 2 Biblio: William Collins/Australian War Memorial, 758pp, $35.00hb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Apr_2021/1332086837.0.l.jpg

In World War II, Australian forces again had to cross the Indian Ocean to fight in the Middle East, while the outbreak of war in the Pacific at the end of 1941 confronted Australia with the first real and direct military threat in her history. In his war memoirs, Winston Churchill wrote of how naked and exposed he felt on hearing in December 1941 of the loss of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse, Britain’s only capital ships in Far Eastern waters. How much stronger was that feeling in Australia, now that the Singapore strategy was crumbling and the fragility of the British and dominions’ position plain for all to see.

Naval thinking before World War I generally emphasised the ‘big battle’ approach. As long as the enemy fleet was destroyed or at least contained, Britain would have command of the sea and would thereby be able to protect its own movements while denying the same to the enemy. Accordingly, Britain would maintain a huge battle fleet concentrated in the strategic area, ready to seek out the enemy and bring it to battle. Paralleling this control from the centre was the understanding that the dominions would provide for their own coastal defence against minor incursions. The Trafalgar complex blinded the Admiralty to the dangers of what late nineteenth-century French naval strategists had emphasised, guerre de course, privateering or commerce raiding. It was confidently argued by almost all observers that twentieth century industrial economies could not withstand the pressures of a protracted war, and that any future conflict would be short and decisive. In those circumstances, the slowly-felt effects of commerce raiding – or on a wider, more organised scale, economic blockade – would be irrelevant, as well as a distraction from the primary task of bringing the enemy fleet to the decisive battle. It was partly for these reasons that the Admiralty stoutly resisted the introduction of the armed convoy system, arguing that escort duty was an improper use of naval power. By early 1917, therefore, Britain was within weeks of starvation.

Australia never found itself in that dire position, but it did face serious threats from German commerce raiders which interfered with her shipping links with the rest of the world, including the vital route to Britain. Robin Bromby tells the story of these raiders with skill and insight. The lingering sense of chivalry at sea (notwithstanding the final actions of the Sydney’s captain against the Emden), the exotic settings, and the small casualties might add up to a Boys’ Own adventure, but there is a more sober side to the account. Luck played a considerable part in the outcome of the Australian and New Zealand encounters with the raiders, and had it favoured the Germans more often, their ships could have wrought far greater havoc on the dominions’ maritime communications. As it was the Emden terrorised the Indian Ocean for months before being destroyed by the Sydney off the Cocos Islands in November 1914. Bromby has combed the secondary literature thoroughly, and he writes well. Handsomely illustrated, the book is a pleasure to read.

As part of its programme to keep the official histories in print, the Australian War Memorial has combined with Collins to republish World War II volumes over the next several years. This is a worthy exercise, for with all their shortcomings, and despite the suspicions that still attach in some circles to the very notion of ‘official history’, these series remain the most solid achievement in the writing of Australia’s military history. The text, maps and illustrations are unchanged from the original edition, with only a short introduction by a contemporary historian to mark the new edition. Recent scholarship has questioned some of the judgements in the official histories, but overall, they stand up to the passage of time remarkably well. While a volume such as G. Hermon Gill’s Royal Australian Navy 1942–1945 will never be recreational reading, it will continue to be a mine of information on the exploits of the R.A.N. in the latter part of the war. It is good to see these volumes available again.

Comments powered by CComment