- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Great Photographs

- Article Subtitle: Pity about the speech

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Donald Thomson was an altogether extraordinary man. We are fortunate that at last some of his great legacy to us is being published. It was my recent fascinated delight to read his Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land (Currey O’Neil, 1983) and now, only a few weeks later, to find this equally fascinating book on my plate for a short review. I knew him, although not well, when he and an assistant and his collections were housed at the University of Melbourne in various parts of that jumble of old buildings on the comer of Tin Alley and Swanston Street which also held Trikojus’s Biochemistry Department. Where he kept his Aboriginal canoes later became our departmental tearoom and what had been his office later became our Professor’s office.

- Book 1 Title: Donald Thompson's Mammals and Fishes of Northern Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Thomas Nelson, $35, 210 pp

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Few of us had the perception, wit or courage to get to know him well. He was formidable, remote, eccentric, and utterly devoted to understanding the whole relationship of the people of Northern Australia to their land, plants and animals. His experience of these people and their environment of course quite transcended anything that his biochemical colleagues in proximity had experienced. But he was there, there were many stories about him, and some of us wondered just who and what he was.

Gradually the real story is emerging. He was a hero, dedicated and quite magnificent, and now, twenty-five years after his death, with his eccentricities properly faded, the real achievements are emerging. When I knew him he was soon to mount his expeditions to the Bindibu people of the Western desert and some of us were lucky enough to hear him talk and see him show his superb pictures of these journeys. I have a ridiculous memory of one night when a distinguished professor of the University chaired a meeting at which Thomson was to speak of his discoveries amongst these remote tribal people. The professor in question had been a staunch protagonist of Thomson’s in those interminable years when Thomson staggered from grant to grant (at one stage he was a research fellow in Anthropology to the Chancellor!) and that evening the professor certainly drew on the resources flowing from that protagonism. To the best of my memory his introduction lasted almost 45 minutes. When finally he called on the speaker to give his address, Thomson, who had been looking daggers at the chairman for a long time, simply said ‘Well, Professor X has said all I had to say, so I’ll just show you the pictures’ – which he did with the minimum of words and we all went home. You should certainly read as well Thomson’s Bindibu Country (Nelson, 1975).

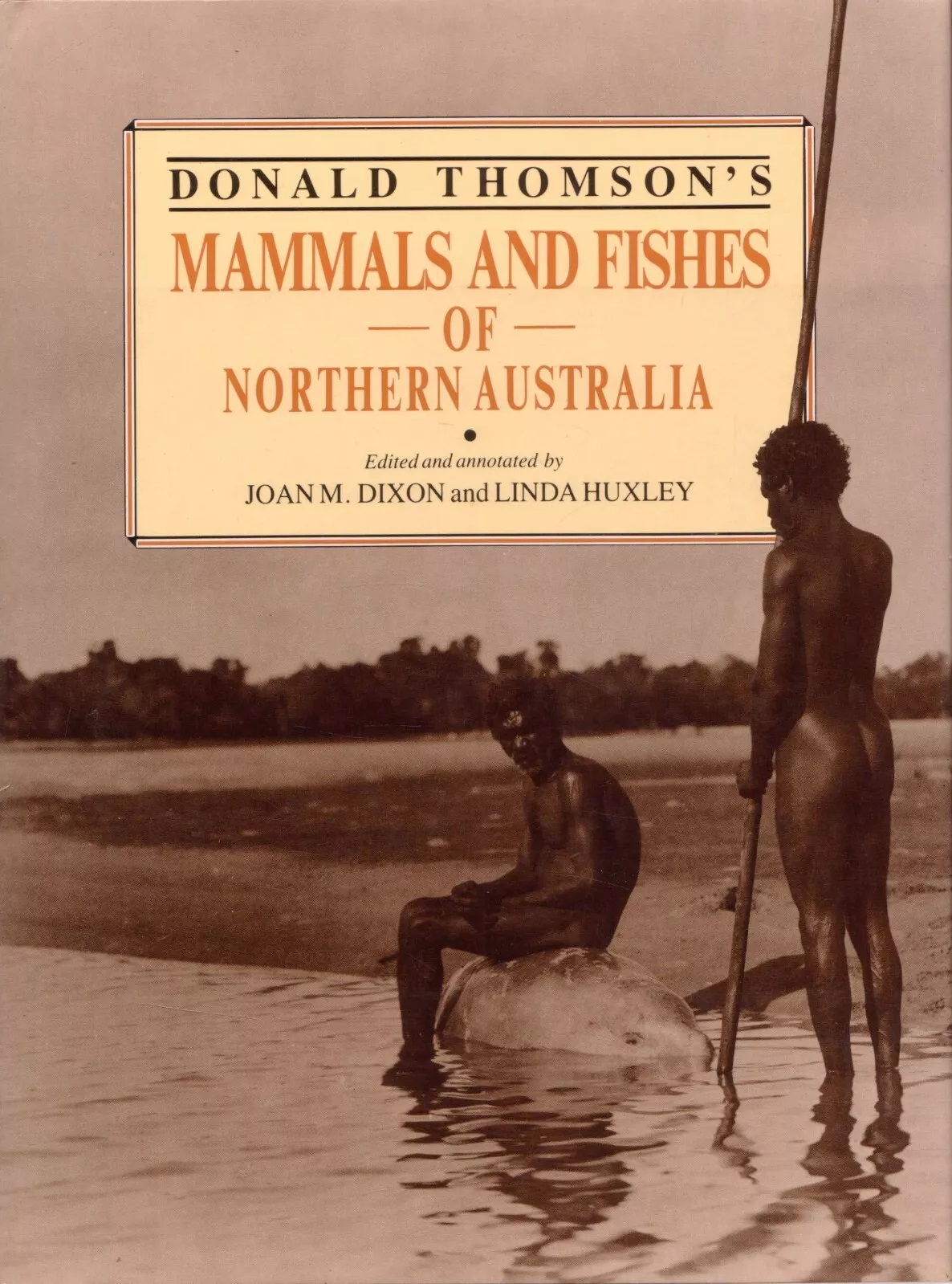

His great collections of anthropological, zoological and botanical materials belong to the University of Melbourne and are largely housed at the Museum of Victoria along with thousands of photographs and manuscript notes. They are a treasure which is bit by bit being revealed to us and this book is the latest instalment. It is a scholarly but easily readable book which also contains nearly 100 of his arresting black and white photographs. There is some evidence that his photography was inspired by Scott’s great photographer, Herbert Ponting, and it has something of the same quality. One of the great tragedies of Australian anthropology is that the cinematographic records of his travels in Arnhem land in the mid to late thirties were lost to fire whilst they were stored in a government warehouse. This goes a long way towards explaining why he thereafter kept everything he had collected close to him.

But now his treasures are being opened up to us and we should honour him and pleasure ourselves by buying the books – seek out this one and the other two I have mentioned. In order to spur you on, let me finally tell you of an odd experience I had relating to Donald Thomson. About 1948, I was secretary of the Science Club at Melbourne University. It fell to my privileged lot to approach the great ethnologist Leonhard Adam, author of Primitive Art (Pelican Books, 1940), and ask him to speak to our student club. This he charmingly consented to do and then showed me some of the notable works of primitive art he possessed and which my university in turn now possesses. Impulsively I told him that I worked in the next room to Donald Thomson. As I remember it he said, looking over the top of his halfmoon spectacles, ‘I have never had the pleasure of making Dr. Thomson’s acquaintance.’ I most vividly remember then offering to effect an introduction. On reflection, I think that my error of taste at the age of twenty was much less than his error of scholarly communication at the age of fifty-seven. I urge you not to repeat Leonhard Adam’s error.

Comments powered by CComment