- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nameless Journeys

- Article Subtitle: Choices and Chances

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

These two first novels join the rapidly increasing library of fine and varied fiction being written by Australian women. Pairing them in this review is entirely fortuitous, and it is always possible to construct a comparison between any two books with a little ingenuity. I would want to stress the contrasting ways in which these authors explore very different aspects of female experience. However, at this juncture I am also particularly conscious of the doubtful position a male reviewer takes when he wishes to praise women’s fiction in this way. It is one thing for men imbued with a dash of new consciousness to recognise the positive examination of women’s lives in fiction; it is quite another for them to hold it up to (masculine) judgement. Despite the passage of virtually a generation, I’m uncomfortably aware, as I write this, of some remarks made by Mary Ellmann in Thinking about Women:

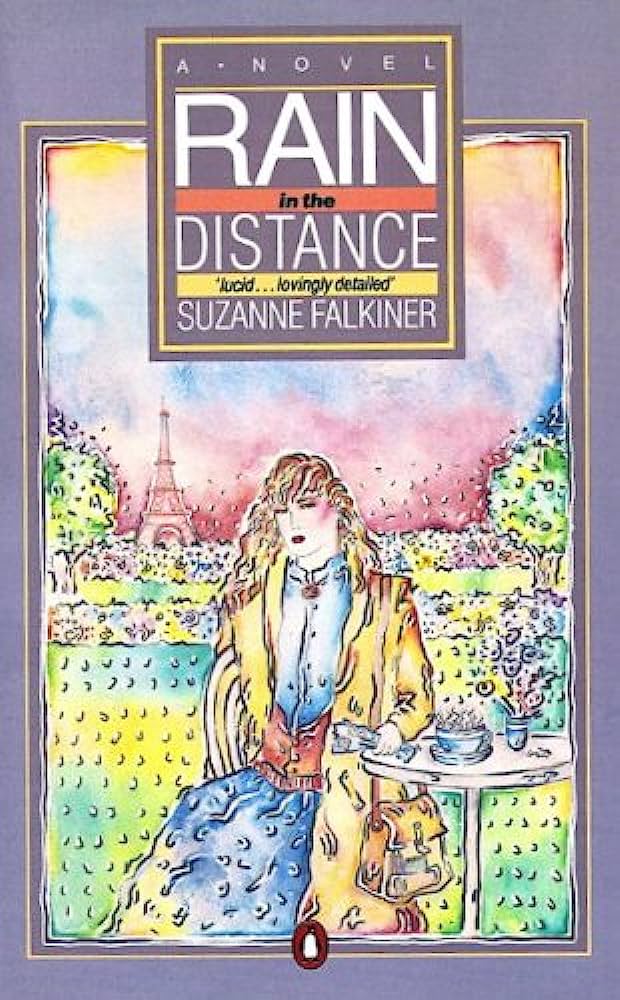

- Book 1 Title: Rain in the Distance

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $7.95 pb, 162 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

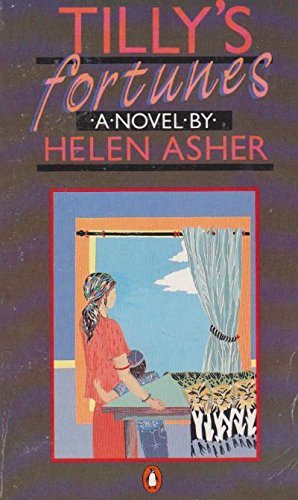

- Book 2 Title: Tilly’s Fortunes

- Book 2 Biblio: Penguin Books, $6.95 pb, 149 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

With a kind of inverted fidelity, the discussion will arrive punctually at the point of preoccupation, which is the fact of femininity. Books by women are treated as though they themselves were women, and criticism embarks, at its happiest, upon an intellectual measuring of busts and hips.

Of course Ellmann was satirising an overt literary chauvinism, but I take her warning to heart while trying to maintain a very different stance from the one she deflated so successfully. In fact, male complacency in its many manifestations is implicitly undermined by both these novelists. Tilly’s Fortunes is a black fable about internalising the traditional female role, which leads to the solitude that is foregrounded in Rain in the Distance, a novel centred on a more ‘contemporary’ heroine.

In Tilly’s Fortunes Helen Asher skilfully presents the first-person narrative of a woman who appears, at first, as half-mythical. She recalls her own birth in great detail. She is the girl with golden eyes. In the course of the narrative she moves towards a fairy-tale fulfillment, where she will compensate for the loss of her mother through the repetitive rhythm of bearing her own children. Throughout the novel, as Tilly grows from child to woman, the naive, reductive narrative style mirrors her responses:

It is the future I am really concerned about. To bear children will be my purpose and the content of my life. This, of course, came about with Carter’s consent. We haven’t set a limit to the number of children. The reason for wanting them is that it is natural.

The fairy-tale quality of the novel is enhanced by its settings: nameless countries, towns and cities. Tilly ends up living with her husband Carter in the satellite city called Golden Grove. When the girl with the golden eyes settles in Golden Grove and has five children we enter the realm of John and Betty. Carter, a computer engineer, takes a trip to Africa and returns with a changed view about the self-indulgence of producing children: Given the epigraph, a quotation from Jo Vallentine, the novel could at times be read as a didactic fable about fertility and responsibility, but that would be to oversimplify its tone. Carter in fact becomes an avenging force linked to what Tilly has repressed in order to live her contented life. We are reminded, if we dismiss Tilly too easily, of a much earlier conversation with her uncle:

‘You’re not like your mother,’ he said and took the ladle out of my hand. ‘You shouldn’t always be so smart.’

‘Why,’ I said, focusing on his bushy eyebrows. ‘Would you prefer me to be dumb?’

The violence at the end of the novel spirals back through its atmosphere of fantasy, highlighting, for example, Tilly’s experiences in factories as one of an army of female workers who have completely absorbed the values of the assembly-line: ‘Most women are proud to be fast workers’.

The unnamed narrator of Rain in the Distance pits herself against the assumptions that enslave Tilly. Born in 1952, she takes the escape route of the 1970s for Australians in her situation: travel. But as the narrative keeps returning to her childhood on a New South Wales sheep station, she recognises her affinity with her rebellious mother: ‘At parties she laughed with the men. Not surprisingly, I found out later, most women do not like her.’

The novel takes the perhaps rather cliched form of recounting a geographical journey that is really a psychological, inward journey. The problem of tone that often besets this kind of first-person narrative seems to me to mar the central part of the novel. It is impossible to detect any distance from the narrator’s hackneyed reflections on the need to leave Australia, or from the very 1970s romance of foreign cities, lovers, aimlessness. But in general the intricately woven structure saves the narrative from becoming too self-indulgent. The powerfully written epilogue finds new reverberations stemming from the narrator’s solitude, as her account of her life gathers up the last shreds of the past. The childhood impression of Mrs Frampton, a widowed neighbour (‘Why is it that women living alone take on the imagery of monsters?’) is transformed into the narrator’s consciously created independence: ‘After a while I became aware of the necessity of establishing a country of my own’.

The complex interweaving of the narrative is the pattern that the narrator, in the midst of her journeys, cannot find:

Here in my room. in the silence, I look at the last entry in this battered exercise book. I am looking for a pattern. But no pattern emerges, no structure. There seems to be so little to catch hold of, only the things that happen.

The life that the narrator is able to carve out for herself points to the sense of possibilities felt by a different generation from Tilly’s. But an early remark made by Tilly underlines the power both these novels exert on the reader: ‘In books people reveal their secrets and unfold from mysteries, and some are funny’.

Comments powered by CComment