- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

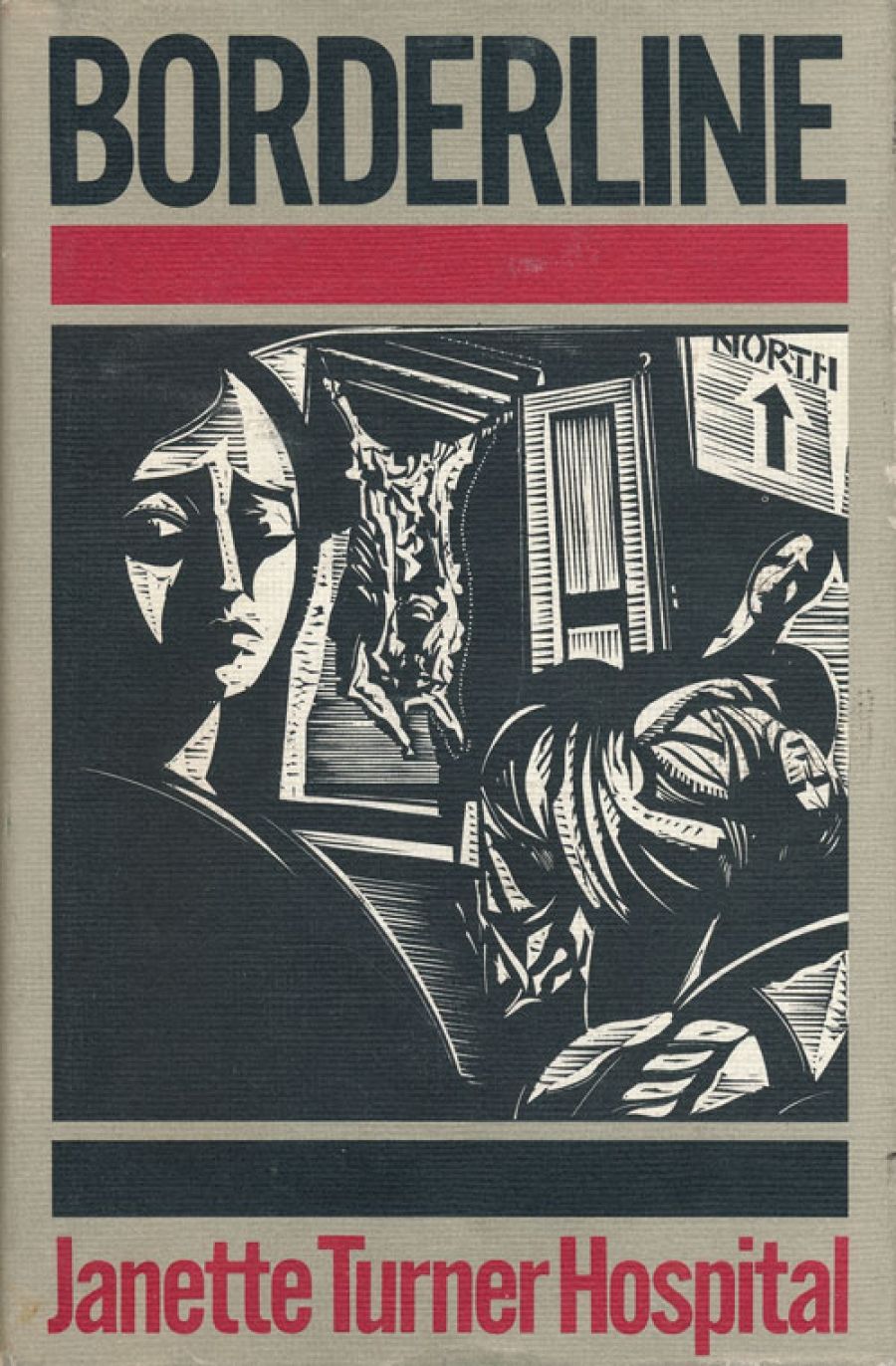

Janette Turner Hospital was born in Melbourne, but has lived and travelled abroad in recent years. Borderline, her third novel, is set for the most part in Boston and Montreal. It is a mystery story which contains many of the conventional ingredients of the genre: disappearances, murder and violence, mysterious messages. However, these things are subsidiary to its dominating theme which is an exploration of the nature of reality. In this it achieves mixed results, but on the whole favourable ones.

- Book 1 Title: Borderline

- Book 1 Biblio: Hodder & Stoughton, 287p., $19.95hb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/RzDN2

Jean-Marc Seymour is the estranged son of a temperamental, eccentric and successful painter. JeanMarc is a piano tuner and a keen observer of the world about him. To both occupations he applies the same practical skills: ‘It is the minute adjustments that count. I work with what I have, I untangle the out-of-tune world. Note by note. It’s something’. The narrative voice in Borderline is that of Jean-Marc (unfortunately, though, it is not always clear that this is so), and he purports to be writing history. But as he says halfway through his story ‘the past … is a capricious and discontinuous narrative, and the present an infinite number of fictions.’

In other words, reality has no clearly defined borders. The point is made consistently, and sometimes clumsily, throughout the book in which many kinds of borders are explored. There are geographically defined borders between countries; there are borders, perhaps barriers, people mark. out between themselves; there are shadowy borders between the spiritual, the temporal and the physical; and most important in this book there are difficult borders between reality and art.

Jean-Marc tells his half-sister, Felicity, that ‘one art historian, one gallery curator, can save a painter or two from oblivion. One well-tuned piano is worth a roomful of concert performers’. Felicity herself, the model for many of Seymour’s paintings, questions her own reality. Frequently she feels trapped: inside the paintings: ‘Perhaps it’s true’, she tells Seymour, ‘what you’re always saying in interviews. That I’m a figment of your imagination.’

That she may actually be so is one of the mysteries which confronts the reader. According to Jean-Marc, Felicity has disappeared. So too has Gus, a blundering Canadian with whom Felicity became entangled at a Canadian-United States border crossing. Also caught up in the entanglement is a refugee from El Salvador who bears a vivid resemblance to a painting of St Mary Magdalene by Perugino. The lives of all three are immediately redirected and threatened by dark forces they do not understand. The story shifts quickly between Boston and Montreal. Seymour, the painter, is outside it yet a part of it as he works obsessively on a new series of canvases in his studio. It is Jean-Marc who follows the events through occasional meetings but more frequent telephone conversations with Felicity and Gus. And then the border trio disappear.

Jean-Marc records the past events as a capricious and discontinuous narrative. In a final chapter he writes about the present, but the mysteries are unresolved, the fictions remain open to the choice of the reader.

Borderline is an intriguing novel. Hospital is a talented and colourful writer, although occasionally a little too clever at the risk of obscurity. Some of her aphorisms and metaphors are delightful: ‘Be careful. Your wish may come true’; ‘I’m right in the middle of the end of an affair’; ‘the light came at them like a tiger’; ‘yesterday was a hypothesis existing purely by the grace of today’; ‘any sane person would surely agree that it is quite irrational to feel guilt’.

Comments powered by CComment