- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: It’s All in the Title: Some have it

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It was a comparatively easy task for Anna Murdoch to have In Her Own Image published. After all, as the critics vied with each other to point out – Rupert does own forty-two per cent of Collins. A cynical observation is that she had considerable difficulty in having it seriously reviewed – when one considers how many critics Mr Murdoch has at his disposal! Everyone wrote about it of course – after all, the Murdochs make good copy. Through her many interviews, we learn a good deal about Anna Murdoch and pick up a few pointers about Rupert the family man – but relatively little about the novel itself.

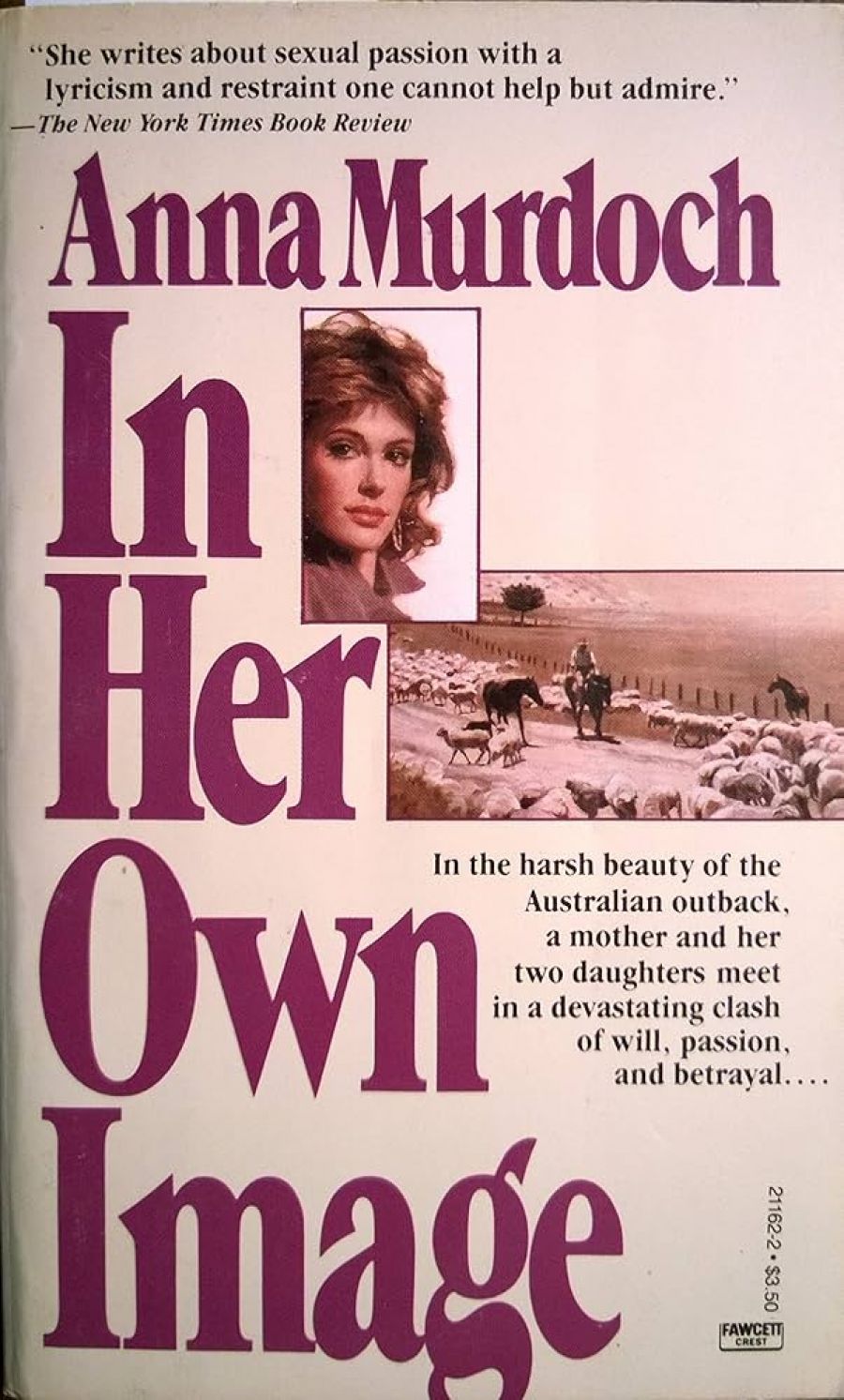

- Book 1 Title: In Her Own Image

- Book 1 Biblio: Collins, $17.95 hb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The Sunday Times, for instance, a forum for critical reviews, devoted 288 column lines to discussing Mrs Murdoch’s problems and vicissitudes as budding writer, mainly in the light of her marriage to Rupert. Of these, five lines spelled out the plot: five lines pronounce judgment. Predictably, these were both favourable and vague. Phillip Oakes wrote, ‘it is in fact a highly accomplished novel – shrewd about family relationships, haunting in its evocation of time and place’. It’s a pity he didn’t feel he had sufficient space to support his claims. Henry Stanhope in the Times evades the issue by devoting thirty-five of his forty lines to the story concluding from scant evidence, ‘this is a promising first’, and the Yorkshire Post even more timorously, in quite a lengthy article, skirts the issue altogether: the Times review of the book called it a promising first. Tempting as it is to say, well they would wouldn’t they, you have to agree it is ‘a good read’. The critic for the Observer doesn’t appear to have read the book at all! ‘The publishers have assured me the book is very good indeed.’ The Guardian simply enjoys a good dig at Mr Stanhope: ‘Treachy yes. But very diplomatic.’ The Sunday Express in fact managed two articles. The first, (191 lines), makes no reference to the novel at all, only to the fact of its publication and the second, one feels, would have made the obviously intelligent Mrs Murdoch cringe: ‘A good one for the girls’, it proclaims, adding that while most men would be bored, ‘Mrs. Murdoch can write … many women will read it with pleasure.’ The Daily Mail allows, ‘the dust and flies, the sweat, the scorching heat sizzle off the pages’, while the plot left the reviewer ‘cold’ and the Daily Express writes titillatingly of ‘hot passions on an Australian sheep farm’ adding somewhat curiously that ‘it is accomplished if too solemn’. The Financial Times’ critic in a masterly display of vague understatement writes, ‘The writing, the insights, the way it deals with its not uninteresting theme – none of these are noticeably good or, for that matter, noticeably bad, though the setting is unusual.’ It was left to the to Daily Telegraph to make any honest, if minor, attempt to square with the novel. Its small review is at least fair to the novel’s concerns and concludes, ‘Anna Murdoch is a good descriptive writer and makes telling use of Australia’s stifling heat and dry barren country, although the portentous narrative voice grows monotonous some while before the end.’ There is just the feeling here that the critic has read beyond the dust jacket!

Mrs Murdoch, it’s sad to point out, fared no better in Australia – at least, in the articles at this reviewer’s disposal. They were full of the same concerns: Mrs Murdoch’s charm and beauty: her nervousness about breaking in on Rupert’s territory and continual cynical references to her husband’s holdings. Louise Carbine’s writing for the Age, was most eloquent when writing about the explicit sex scenes in the novel. ‘It made David McNicol rattle the ice cubes in his orange juice,’ she says. Apart front a thirteen-line quote from a major love scene, she failed to evaluate the book at all – leaving it as the Observer critic did – up the publisher. Anna was, she tells us, ‘thanking her publisher who, full of nervous conviction described In Her Own Image as an exciting first novel, a compellingly readable book’. The Weekend Australian escapes with few generalities and then goes on at length to try to place Mrs Murdoch in the women’s movement and the National Times in a full-page coverage adroitly avoids criticising the novel at all. Even the Herald, another Murdoch stronghold, fails to pay Mrs. Murdoch the compliment of a serious review: ‘It leaps up and startles people who know Anna Murdoch’ explaining this statement in an aside later on ‘it makes the passions in The Thorn Birds look like Postman’s Knock.’ It’s hard to accept that telling us the characters are ‘vicious’ and the drama ‘searing’ constitutes a serious evaluation of the novel!

So many words, well over two thousand column lines in fact, yet so little criticism. It’s a curious situation when we learn the novel is to be published in America, South Africa, Italy, Finland and Sweden. Perhaps Mrs. Murdoch is being a trifle naive when she claims the book wouldn’t be published if it weren’t any good but the lack of serious evaluation indicates a remarkable cautiousness, to put it tactfully, on the part of its critics.

It is indeed’ a ‘promising first’, if flawed novel. When evoking the Australian landscape Mrs Murdoch is masterly, as many critics indeed point out. ‘The river snaked lazily around the property creating a globular peninsula in which the houses. and the stables, the yards and the shearing sheds, were scattered with no apparent design. The trees in the bend of the river shimmered silver in the stillness and beyond the trees, the hills of the Murrumbidgee country lay gently and endlessly blue.’ Yet in writing about people Murdoch exhibits little of the same control. She clearly finds people more tricky. Liz and Josie, inherently interesting and commanding characters are at times reduced to the worst kind of romantic toshy heroines. B.B. the mother figure, who dominates the story, while convincing as a senile old woman is over-played as the sinister wicked witch of the wood. The male figures fare worse. The plot itself: a family Christmas reunion on a sheep station provides a nicely organised stage or her unfolding drama. Murdoch is quite realistic on this point. ‘I wasn’t sure I could handle anything longer than that’ (The Yorkshire Post). But this novel is more than story of ‘hot passions on a sheep station’. Murdoch tells us in an interview, ‘I’m very conscious of being a mother and of the influence on my children’ (The Herald) and this concern forms a central theme to the novel. Conscious herself of ‘giving her daughters ambiguous messages’ (The Weekend Australian), the writer has intended to explore the machinations of female behaviour locked into stereotype roles white trying to assert their individuality. The idea is interesting but in the main unsuccessful.

Liz and Harry Barton run Tiddalik, a property in Northern South Wales, with the help of it seems a permanently drunk farm manager, Jim, and his mistress, an aborigine home help, Cynthia. With them live Liz’s aging and pernicious mother B.B. While the ‘too damned good looking’ Harry occupies himself with sheep breeding experiments his childless wife ‘engulfed in her barrenness’ and embittered by a loveless childhood stands emotionally frozen in her: world of self-imposed order, desperately hoping to hold fast her two loves, Harry and Tiddalik. Her rigid controls are shattered by the arrival of her sister Josie from New York. Josie has returned to Tiddalik to ‘face up to the truth … her true feelings for Harry … the most real thing she knew.’ In tow is Josie’s son, a gentle and intelligent boy of twelve. Supposedly the son of Michael, Josie’s Jewish husband, we learn he is in fact the result of a passionate liaison between Josie and Harry prior to their respective marriages. Harry unaware of his paternity is informed of this fact by the evil B.B. – over the family’s Christmas lunch. And so unfolds the drama! In the ensuing chaos Liz and Harry spit out the butt-ends of their personal conflicts: a torrential storm blackens the sky and cuts the power: Alex, Josie’s son, runs away in horror and confusion: Cynthia gives birth and B.B. is burned to death in her cottage with no-one being seriously inclined to save her.

A grossly negligent and uncaring mother: a much married floosie: a ‘saxophone playing barmaid’, come dressmaker, B.B. is the viper in the hearts of the protagonists. Liz has been scarred and embittered into adulthood. Josie reared by Liz, has never grown up. Their father had died a disappointed and broke man. Jim, the farm manager, has murdered on B.B.’s behalf and Alex is grievously hurt by her. While she lives ‘under sufferance’ at Tiddalik, it seems no-one is free of her invidious power. It is only when ‘the old bitch’ is gone that everyone appears to be able to take control of their lives.

Whilst accepting that B.B. is a destructive mother – the scatty and irresponsible old woman we meet at Tiddalik seems to wield unreasonable power over her adult daughters. Josie is instantly frightened of being enmeshed in her power again and Liz spends her days battling with her for supremacy. Her blatant cruelty in betraying Josie’s secret in fact comes out of her need to get even with the sharp-tongued Liz! Apart from this horrendous act the most convincing descriptions of B.B.’s state of mind are told us by Liz.

Anna Murdoch writes best about those people she understands, Liz and Josie and the boy Alex. The Yorkshire Post quotes her as saying, ‘It’s not autobiographical but the two sisters do show both sides of (my) own character.’ The sisters are not uninteresting, but the constant teetering between sensitive feminine insights and melodramatic romanticism inevitably devalue the work.

But at the end of the day, are we really interested in the fate of any of the characters in the novel? We are invited to believe that B.B. alone is responsible for the family’s failure to take command over their lives. And this is a real problem with the novel. Anna Murdoch wants us to see her women as victims, but their assertions of individuality seem rather juvenile. Liz for instance, makes a deal with God for a baby by giving up her painting. Josie finds nothing untoward in returning to claim her sister’s husband after a one-night stand twelve years previously. What they learn is cliched. Liz learns she is just another ‘failed floored human’, Josie recognises that she has quite a good bit of the old B.B. in her, and Alex learns to be a man. But what one does remember from this novel is Anna Murdoch’s powerful evocation of the Australian bush. Her small observations of everyday life on a sheep station are beautifully written and caught, and it is here that we feel the potential for further writing. The Financial Times summed it up as ‘an undemanding read’, and The Dust Jacket argues it’s ‘compulsively readable’. Well, it isn’t either.

Comments powered by CComment