- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Subtle-tasting experience, dating back more than ten years, has made me suspicious of ideologues who take pen to comment on Their Own. Whether they’re, say, reviewing the fiction or writing the history of Their Own, the continuing good of the Cause tends to be a primary consideration. So my sceptical heart sank when I heard that the biography of James Duhig, Catholic Archbishop in Brisbane from 1912 to 1965, was being written by Father T.P. Boland, a priest of that diocese.

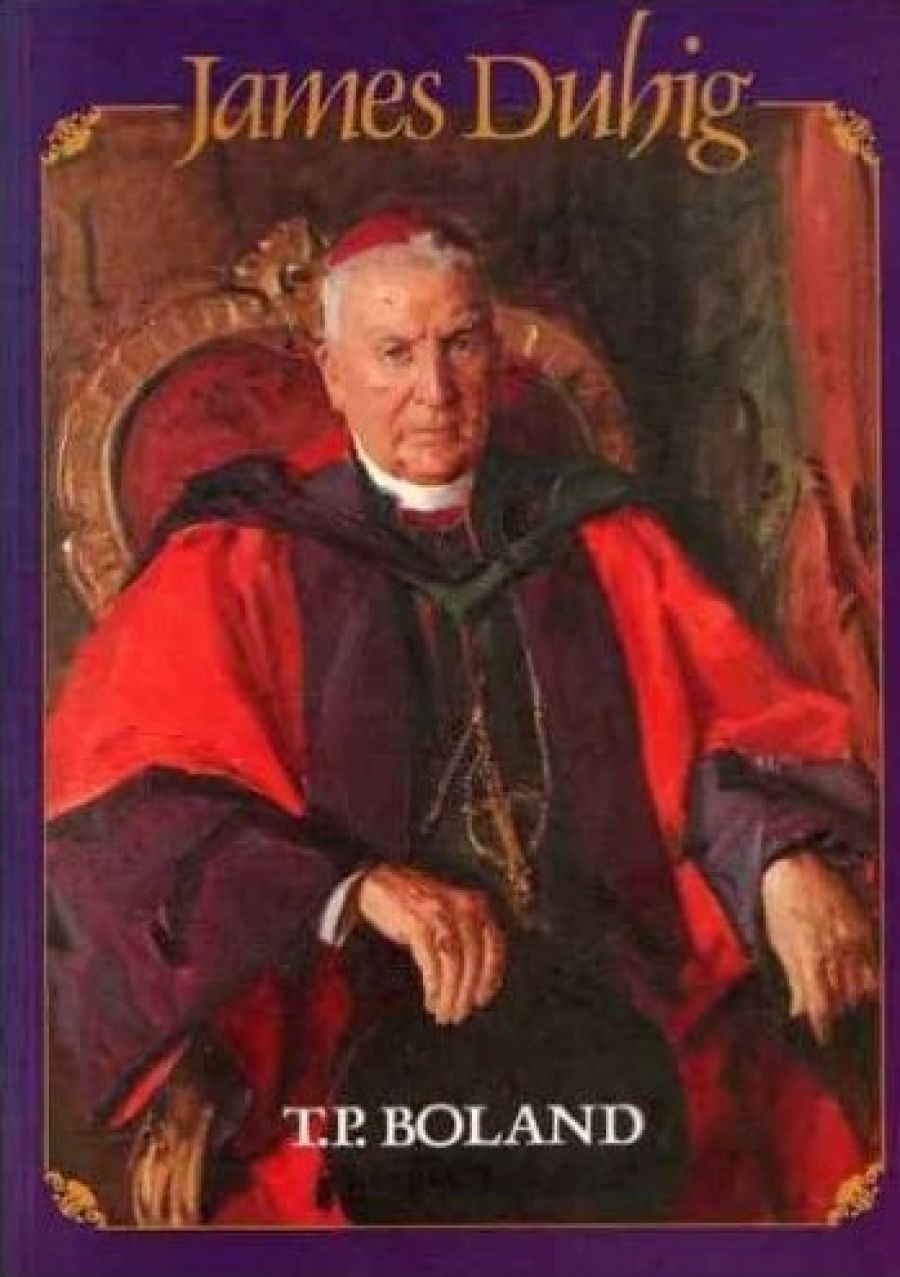

- Book 1 Title: James Duhig

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 435 pp, $40 hb

My first bite of the finished book realised all these fears. Pages four to eight are the worst few paragraphs I have run my eye over in years. The problem is that hoary one of Ireland; substitute myth for fact, then use the myth as an explanation for, in this case, James Duhig’s adult proclivities. After a generation of superb modern Irish historiography, Fr Boland can still quote the Jesuit W.J. Lockington’s The Soul of Ireland (1919), one of the silliest, most vapid contributions ever to a romanticised image of Ireland. In keeping with this outlook, Boland can write, ‘the Irish peasant knew how to act and react in any circumstances in which he was likely to find himself’. This statement of psychological stability hardly squares with Jonathan Swift’s ‘a house for fools and mad’, nor with the incidence of asylums in Ireland, nor with modern scholarship on insanity and psychological disorders among the Irish. And no book that is a treatment of a religious subject and starts with nineteenth-century Ireland should ignore S.J. Connolly’s ground-breaking Priests and People in Pre-Famine Ireland 1780–1845. And, crowning horror, delendum est the statement, re Duhig’s father and the Great Famine: ‘Not many nine years olds lived through it.’ This nonsense is worse than a legion of pigs grunting begorrah.

Then, lo, James Duhig leaves Ireland and comes to Brisbane in 1885 at the age of thirteen, Fr Boland moves into an empirical gear, and the book is transformed. It has 1,667 footnotes. The factual meticulousness is exemplary. For the common reader, the acid test of a biography of Duhig must be its treatment of the subject’s financial dealings, particularly over Roma Oil and the Holy Name Cathedral. On these issues, I would dare to say, Fr Boland has spoken definitively. His herculean progress through the Augean mire of correspondence, accounts, invoices, geological reports, architects’ specifications etc. etc. should qualify him for instant election to the Society of Chartered Accountants. His conclusion is that when it came to these and other financial dealings, Duhig was occasionally unwise, but nothing worse. The man’s abiding passion was real estate but his ability to finance was not on a par. Boland’s most consistent use of a fine, dry wit is used to underscore this failing. He comments that Duhig’s primary teacher taught him firm, clear writing, and adds ‘nobody ever taught him to count’. Elsewhere he comments on the detailed expenses ledgers of Duhig’s episcopal predecessor, and Duhig’s insouciance about such items; ‘Duhig’s business specialty was spending, not accounting for what he spent’.

Duhig chalked up a good score of peccadilloes – amusing to his friends and to this book’s readers – but not usually desirable in a good Catholic prelate. He played fast and loose with instructions from Rome. Church Law for example forbade sales of land over £1,200 without Roman approval. Duhig’s entrepreneurship wasn’t going to be stifled by this, and he simply told himself Australian circumstances were different and Rome’s rulings didn’t apply. Boland is as frank and apparently amused by this as anybody, and he is equally honest about ‘doctrinal howlers and downright imbecilities’ in Duhig’s preaching which produced marvels like ‘[Mary] is the child of Heaven, a child of the Immaculate Conception’.

Yet Boland believes that in spite of these foibles Duhig was a towering personality in Australian history, and his most constant manner of making this point is a stylistic one. It goes thus: ‘He [Archbishop Dunne] watched James under his fig tree, another Nathanael in whom, at that stage, there was no guile’, and ‘Leichhardt Street was their [Duhig and his architect Hennessey’s] special stamping ground, along which they laughed like giants to run their course’, and ‘only that [a big mining strike] could wipe out his debts and allow him to build on it his house of gold and gate of heaven’. In Australia the classic example of this use of biblical and liturgical reference to build an epic quality has been an abuse of it; Manning Clark’s imagination-stunting reiteration of a few phrases and rhythms. Boland’s range is wider and never predictable, but his technique is over-elaborate and must frequently be opaque to the increasing majority of people who couldn’t tell Moses from the Mark of the Beast when it comes to the Bible.

In a way, such fruitiness is appropriate to Duhig, but there is a deeper problem here. Boland’s ideological sympathy with Duhig allows him to question aspects of the man’s personality, but he never questions the supposed raison d’être of the man’s career, his religious faith. One hardly takes exception to that. But to portray the life in such vivid biblical terms is problematic. Is that exactly how Duhig saw himself? Or is his biographer creating him thus? I suspect the latter, for in spite of the Boland imagery, this reader at least is not sure that Duhig’s career was specifically or integrally a Christian one. We are certainly never shown the spiritual man inside. There is no account of what would be called Duhig’s interior life – the devotions he had, his habits of prayer, his attitude to God. Countless letters from him are referred to, but not one that betrays any personal spirituality: they are all politics, gossip and business. Duhig was immensely likeable, and his life a great force for good, but this biography doesn’t show that he was what is called ‘a man of God’.

There are other less important omissions, which seem to be due to reticence. Is it true, for example, that the large inheritance which Fr Ignatius Bossence – Duhig’s thorn – found his way to obtaining for himself was actually from immoral earnings? (And in the group photo Fr Bossence is not the fat man, but the small thin man beside him. I have this on the authority of my father who, as a small boy, was taken by Fr Bossence, a great chook fancier, to the Brisbane Exhibition. They spent the entire day casting professional eyes over the chooks. My father remembers Fr Bossence well.)

In a way, perhaps the book is too empirical; if it’s not in the letters or the files, it’s ignored. And facts become an end in themselves; the accounts of death and funeral are undramatic to the point of bathos. But wider questions demand to be asked. Duhig’s practice of cronyism put him in world class. Did he shape Queensland or vice versa? How enmeshed in one another’s toils did he make Church and State in Queensland?

And even too many close-ups are ignored. What about the daily habits of the man? Boland’s irony too often ebbs away, and we are left with a one-dimensional picture. For example, he details how Duhig got, on the cheap, the contents of the Roman palazzo of an impecunious Colonna, and made his own splendid baroque Gold Room in Wynberg, his Brisbane home. But he says nothing of how this splendour degenerated until in Duhig’s later years one could hardly enter the Gold Room for the piles of old newspapers filling every inch of Colonna table, chairs and floor. Who, if any, were Duhig’s friends? Did he drink much? My father recalls that frequently on a Saturday night, after hearing confessions in the Cathedral, Duhig called at my grandparents’. My grandmother sent one or other of the boys to the kitchen to get what was called His Grace’s ‘hot milk with a stick in it’. The boys took delight in modifying the recipe until it became one part milk and nine parts whiskey.

And did the Arch himself, the source of so many other people’s laughs, have any sense of humour? Fr Boland says nothing. My father says he didn’t, but his favourite Duhig story has a neat openness about it. One day my grandfather was giving Duhig a consultation in the vestibule just inside the open front door of Wynberg. Bandages were being unwrapped from the archiepiscopal ankles. A man came to the door. His Grace welcomed him in, and trailing bandages shuffled off to a parlour. Sometime later they re-emerged, the visitor stuffing a wad of notes into his back pocket. ‘Poor fellow,’ said Duhig when the visitor had disappeared, ‘just out of Boggo Road again, and needing something to go on with. Always in and out. Fraud. I asked him why he couldn’t pull himself together. ‘Well, Your Grace,’ he said, ‘it’s like this. The trouble is that whenever I meet a mug I just can’t help taking him down.’

Comments powered by CComment