- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ally is fifty-four when her husband leaves her. Her best friend and her daughter – neither of whom she has ever really talked to before – are each thousands of miles away. She descends rapidly into an undignified breakdown. Retreating from everyone and everything, she grows increasingly fat and fearful. Ally has never been terribly confident in her own identity (‘People tend to look past her, rather than at her. Shop assistants tend to give her bored glazed looks and a sharp “What?”’) and now, unloved and unneeded, she is threatened with disintegration. The woman in the mirror is a stranger, she imagines herself as a white grub that she can make vanish by closing her eyes.

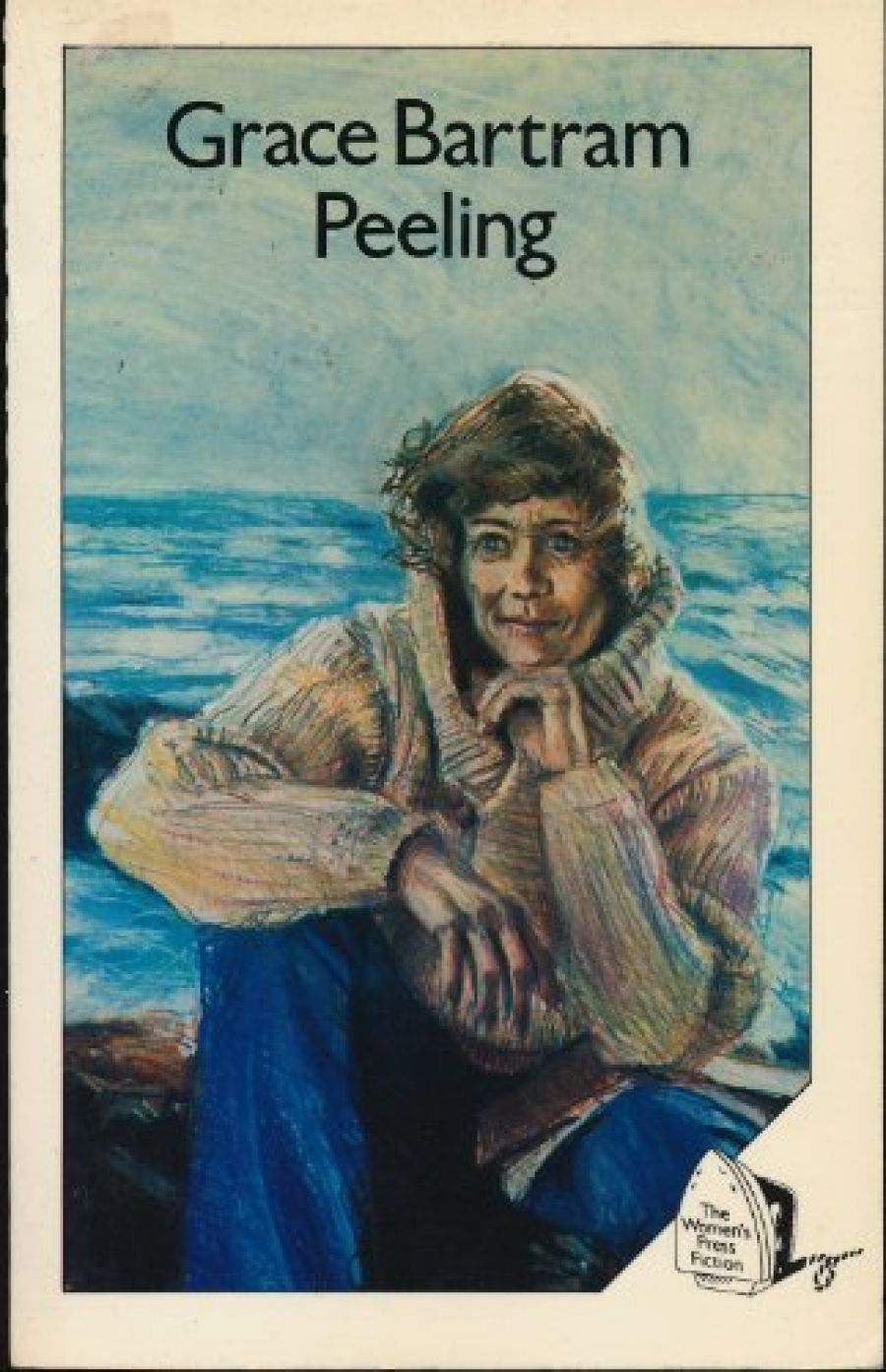

- Book 1 Title: Peeling

- Book 1 Biblio: The Women’s Press, 133 pp, $12.95 pb, $29.95 hb

But not for long. Ally resists, she loses weight and pulls herself together. The real turning point comes, however, when she responds to an advertisement in the local paper and becomes a volunteer worker at a women’s refuge.

Here she learns that she is not alone, that every woman has a similar story. As one of her co-workers explains, ‘it’s a two-way exchange … when you’re talking to women in crisis. A lot of what they say, what they’ve experienced, keys into your own life.’

Described on the back cover as a novel ‘that explores one woman’s voyage of self-discovery’, the book struck me as having much in common with the narrative structure of soap opera: a compelling layering of stories that never really penetrate to the core of anything. Endless conflict, endless baring of scars over endless cups of tea. A series of case histories where the roles of counsellor and client, listener and teller are defined but interchangeable. Class and cultural differences are levelled, even sex differences: everyone has their problems, a life of equal value and equal vulnerability. Power is an illusion, a struggle for survival in a competitive world.

Significantly, in a novel where femininity is defined as caring and supportive –nurturant – all the female characters seem to be social workers of some kind, and everyone is a case for a social worker. Unfortunately, Ally’s ‘self-discovery’ goes no further than this: a discovery of a supposed female essence, a maternalness that she has in common with other women, a means of strength and fulfilment if constructively channelled.

So Ally begins the novel as wife and ends it as mother – not such a long journey.

The main problem seems to be that Ally elevates a counselling strategy into a philosophy of life. The essential qualification to work at the refuge, she is told, ‘is to care about other women, to the point where you don’t judge them or lay your own standards on them and you don’t categorise them or patronise them.’

So Ally deals with the world at large as she is taught to deal with people at the refuge: mopping up, caring, mothering. She sees things always in personal terms – in terms of one human being relating to another, one person telling a story and another listening.

Caught up in the day-to-day demands and drama of the refuge she has little time and, it seems, little inclination to analyse her own privileged social position or the workings of a society in which male violence against women is so endemic yet so hidden – so domesticated. She is content merely to listen and pour cups of tea, to bandage horrifying injuries and cuddle bruised and frightened children, to provide shelter for those who ask.

Ally is unable to identify the profound alienation she feels as a product of a particular social system. Lacking the means by which to cast blame on anything larger than a fellow human being, and having only so recently stopped blaming herself, she takes refuge in a refusal to blame anyone. She struggles constantly to keep feelings of anger and bitterness at bay, associating anger with violence and violence with misery. (For one moment, in fact, she even mothers her attacker – having been saved by her dog, and no longer afraid, she tells the man: ‘You’d better get up … That grass is wet, you bloody fool.’

The refuge where Ally works is located in place (‘Parktown’, a Melbourne suburb) but not time. There is no sense of political climate; no mention of unemployment, welfare policies. or housing shortages – as if these things had little or no effect on the lives of women. There is no context in which women’s refuges can be seen as a political intervention, an evolving strategy. The need for shelter and support is, in Ally’s eyes, a timeless one, a human need: ‘ … men need refuges, too,’ she says, ‘only they don’t care about each other as we do, not yet, anyway.’

Refusing to engage with politics, Ally’s feminism is by default conservative, even reactionary. There is a strong sense in which her concept of the refuge is a direct successor to the nineteenth century concept of the home itself – not a place to escape from the confinement of the home, but a place to recreate the home as it should be: a woman’s space, a shelter where sisterhood provides strength. A place where women rule supreme and womanly values of caring and sharing dominate. A home when the home has been violated; is breaking down. A companionable space but nevertheless an enclosed space, another prison. Ally finds a feeling of self-worth because she finds a way to participate in patriarchy: as keeper of this space her role is more bearable. Beyond this, nothing much is changed.

Peeling is a brave attempt because it argues the equal worth of each person’s life and each woman’s story. But it ignores the unequal conditions under which people live and under which stories are produced, authenticated, authorised, and circulated.

The novel fails to acknowledge Ally’s privileged position – in relation to the women at the refuge whose stories she relates, and in relation to the stories interspersed throughout her own (her daughter Jane’s, for example). It is in fact this appropriation of other women’s stories which enables Ally’s own story to attain a kind of transcendence, an authority it would otherwise lack. By emphasising the shared nature of women’s experiences and downplaying class differences and antagonisms, the stories become merged. In the guise of the omniscient author, one voice emerges – a voice very close to Ally’s own. The perceptions and preoccupations of one woman are thus subtly universalised as applicable to all women. (In Jane’s conversations with her lover Marjorie, for instance, one suspects that it is Ally’s own doubts about lesbianism that are being expressed.)

It could be that the novel thus acts, inadvertently, to silence further those it seeks to give voice to.

As Ally herself points out, Paternalism and Maternalism are not necessarily all that different. In many ways they are merely two sides of the one coin.

Comments powered by CComment