- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

About a year ago, when The Woodpecker Toy Fact and Other Stories was just a gleam in its author’s eye, I chanced to hear this very fancifully dressed woman read a story about childhood perception, semantic confusion, and small-town gossip. It was one of those welcome breaks at an academic conference, when we turned our attention from the analysis of art to the thing itself. And it was perhaps the context, along with the exceptional performance of the reader, which made this particular story stand out so vividly. For while it satisfied, they (by then quite desperate) desire to be enthralled by something fictive, it also played up cleverly to the critic in us all.

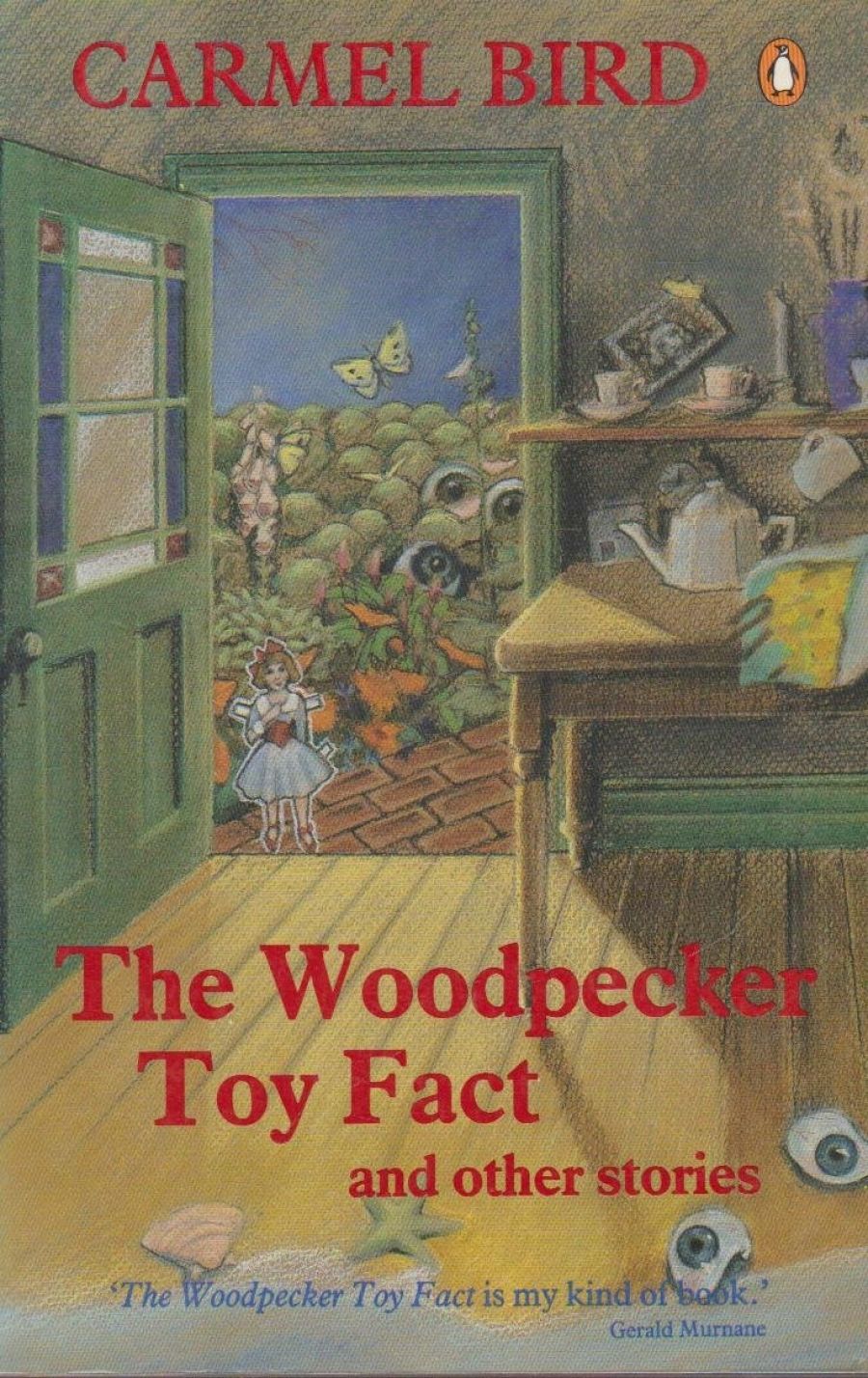

- Book 1 Title: The Woodpecker Toy Fact and Other Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: McPhee Gribble Penguin, 143 pp, $7.95

‘One of the most hypnotic habits of the maggers was the constant µse of the possessive pronouns and parentheses. They constructed sentences which could go on all day in dizzy convolutions as one relative clause after another was added,’ says the narrator, launching into a breath-taking rendition of a very special kind of natural speech:

Edna and Joe (his brother was Colin who married Betty Trethewey who later divorced him which was when he had his breakdown over the Kelly girl so that it was no wonder the business went downhill) were having their twenty-fifth anniversary which was just before Easter which was early that year, and Pam (she’s the daughter, you realize) was there with her fiancé who was Bruce French (his father had the hardware next to the Royal Park) when it turned out that Joe was electrocuted in the cellar which was where he kept the wine (they drank a terrible lot of wine in those days) and it wasn’t long after that that Edna turned round and married Bruce and …

This is Carmel Bird at her best, in her characterisation of certain types of people, bored housewives, little kids, lonely optometrists, small town beauty queens, maggers, barristers, and the like. Their misperceptions, dreams and aspirations are all recognisable, sensitively drawn and entertaining, as are the author’s witticisms. ‘There was a need, in Valerie’s life, for an adjective to go with every noun. She had luxurious towels, elegant armchairs, colonial dressers.’

Unfortunately, however, overshadowing all of this is the dreadful problem of the fairy floss. Before The Woodpecker Toy Fact was a vanity press novel called Cherry Ripe, which Carmel Bird was assiduously flogging with advertising aids in the form of little candy bars at this conference. You can open Cherry Ripe virtually at random and find something like this:

She was sailing through a billowing white night where fog swirled, and palest blood was streaked across the sky. A foaming tide rocked her and washed her out, out into the deep where the tails of giant mermaids slid across her legs, green as emeralds in the sunlight, blue as the night-time sapphire. Beneath her on the ocean floor, rolled a million, million pearls.

The general consensus about Cherry Ripe was that it needed a good editor. Not to stop Carmel Bird from sounding like Carmel Bird, but to stop her from sounding like a parody of herself. And it looks as though The Woodpecker Toy Fact has been treated about half as savagely from an editorial point of view as it ought to have been, though this is already a significant improvement. At worst we now have, ‘Crying pigeons with broken hearts from the glinting green of caverns hollow under sea behind the tormented dark of the blackberry bushes.’ At least it’s shorter.

What’s most bizarre about the writing of Carmel Bird is this unevenness. It is hard to see how the writer of ‘My sisters are married, and all the girls I went to school with, and just about everyone from college, except for a few over-brainy ones and some who were so incredibly stupid and ugly they have probably been put in a home for the incurably grotesque’ can be the same as the writer of this sticky, sentimental froth. It’s as though she’s aesthetically schizophrenic.

It is part of Carmel Bird’s project to deal with the unconscious, to fuse dreams with reality and to integrate the fantasy life, particularly of children, with the waking life of average folk. As epigraphs to the new collection, she quotes both André Breton and Carl Jung. But the problem is that, for her, the imagination or the dream life consists of a certain set of predictable symbols, fairies, blood, the sea, the moon, lace, dolls it’s the imaginative world of a teenage girl who’s plastered her room with unicorns and rainbows. The appearance of the dream world in the stories is signalled both by the introduction of these images and by the sudden disintegration of the prose style.

The real world, on the other’ hand, is signified by any number of things, all kinds of things, the frosted glass window of the optometrist’s shop, the chiffon head scarves, Kentucky Fried. It was the great genius of the surrealists to use those kinds of symbols, the everyday things, in disarray to indicate the dream world, rather than identifying a certain set of ‘unconscious’ images. This, is seemed, was more truthful to experience than is her strict division of real and unreal signifiers or her insistence on a particular ‘dream-rhythm’ and ‘dream-mood’ in language.

Infinitely sophisticated in her perception and description of midlife crises, sexual dilemmas, or daily boredom, Carmel Bird is naïve in her imagining of the unconscious and clumsy in her attempt to portray it.

This is the kind of book that makes you want to wring the author’s neck. It makes you want to invite her to tea, give her advice and cover her manuscript with red pen. I suspect that Carmel Bird, like a lot of us, is in love with that aspect of her own writing that no one else can tolerate. And that the cruel truth which has not quite yet been brought home to her is that you always have to surrender that which you love most. If she only knew how good the rest was.

Comments powered by CComment