- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

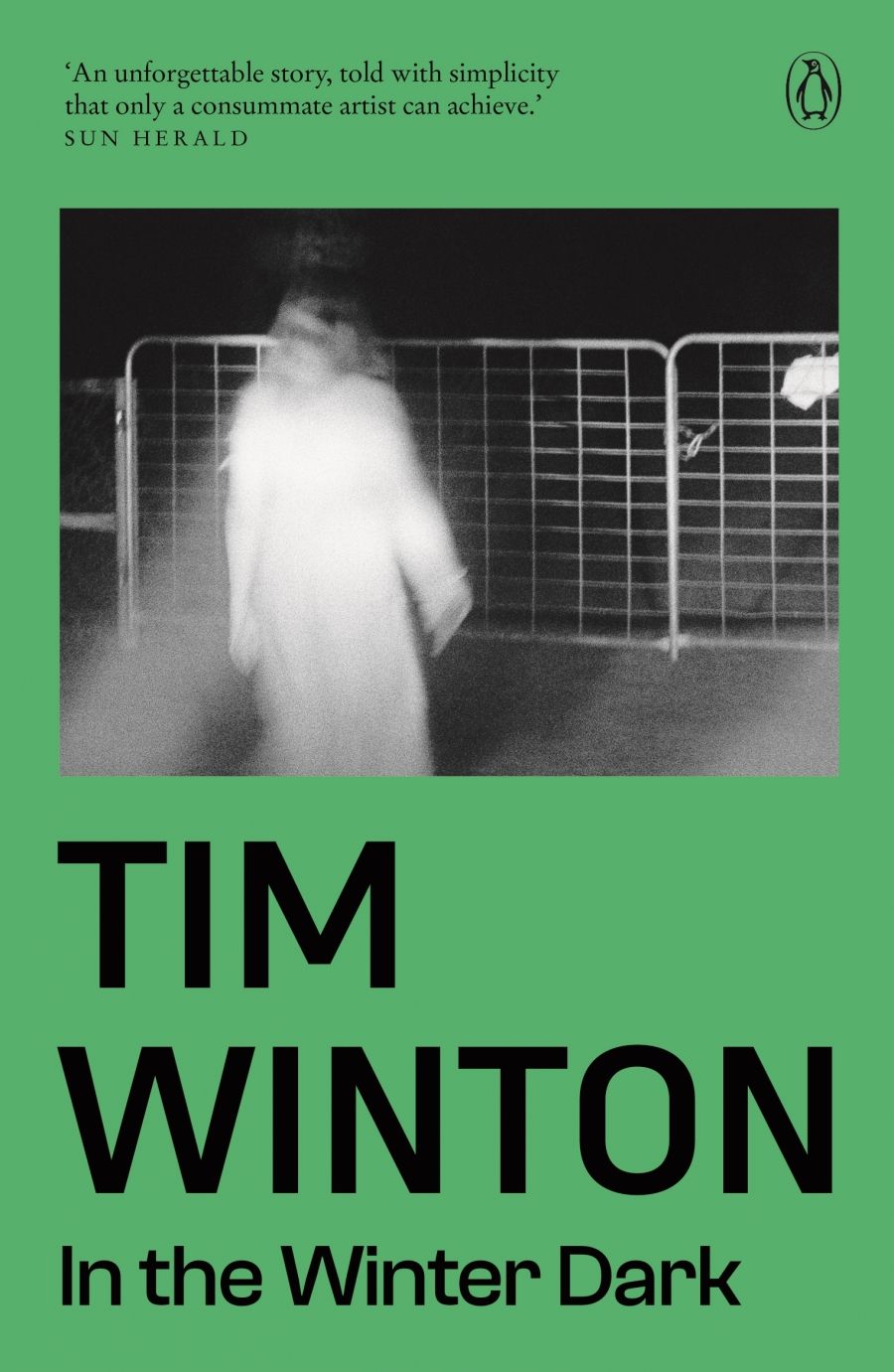

- Custom Article Title: Delys Bird reviews 'In the Winter Dark' by Tim Winton

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Not for the morally faint-hearted

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Place and the specifics of place are supremely significant in Tim Winton’s writing. It has established the South-west corner of Western Australia as its region, and the elements of that area, sea, sky, and forest, recur in his stories, images of an ultimate if unknowable meaning in the world. The people of Winton’s fiction live outside cities, immersed in their natural environment, from which the best of them learn as they struggle to make sense of their lives. Physical and metaphysical frontiers give Winton’s work its special flavour. Placed as they are, closer to nature than culture, his characters and the events of their stories develop beyond the boundaries of what we ordinarily know of ourselves and how we understand the world around us.

- Book 1 Title: In the Winter Dark

- Book 1 Biblio: McPhee Gribble, $24.95 hb, 132 pp

Secrets, guilts, and fears, memories and myth are the pressure of darkness. They create the dreams and generate the events that impel Maurice’s narrative. Three neglected farms lie in the cul-de-sac that is the valley. Its inhabitants don’t interact closely and are separated from one another in different ways, yet they are drawn, or forced together by those pressures. Maurice and his wife Ida live in the house he was born in and farm their property. Murray Jacob lives in the big, whitewashed stone house on the hill, to which he came twenty-five years before when he left the city, fed up with mowing suburban lawns, to watch the grass grow. In an old soldier settlement shack down the valley is Ronnie, a young yuppie dropout, pregnant and abandoned by her boyfriend for whom the valley did not fulfil his shabby romantic yearnings. She has Muscovy ducks, a cow, and a goat.

In the cold darkness of one winter’s night, the valley becomes a fearful trap and the forest a focus of horror for these people. Sanity and reality shift and waver and are distorted into madness and death. The idyll of life in nature becomes the terror of Life in the wilderness. Outside pressures on the valley – the imminent threat of bauxite mining and the interests of real-estate developers – are matched by pressures from within it. Human evil, from the past and in the present, connects these very ordinary people and produces the chain of events that destroy life in the valley. An atavistic, unseen presence (the book is partially and affectionately dedicated to ‘the Nannup tiger wherever you are’), lurks behind it all.

If this all sounds pretty predictable and rather symbolically crude, Winton gets away with it. In the way the narrative moves between the minds of the different characters, weaving into its structure the notion of shared myth, memory, culpability, and suppressed desire; in the mounting claustrophobia of the deliberately hidden life of the valley and the momentum of actions veering out of control, it’s reminiscent in some senses of Faulkner’s techniques and concerns. This is a truly chilling, realistic horror story, rare in Australian writing. Who else does it? Baynton, by using grotesque; Jolley perhaps, certainly in The Well, with macabre elements. But the impact of In The Winter Dark comes from the juxtaposition of its flat, realist prose and the imminence of annihilation.

While the beast that wreaks havoc among the animal life in the valley remains hidden and nameless, it figures as a projection of the fears, inadequacies, and capacity for destruction of those in the valley, types of us all. In the end, only the men are left, sharing new secrets, their ‘terrible truths’, as they wait for discovery or death. Maurice dreams and Jacob drinks and they keep their vow of silence.

Tim Winton’s a young writer in a hurry. Not yet thirty, he’s published three short novels, An Open Swimmer, Shallows, and That Eye, The Sky, and two collections of stories, Scission and Minimum of Two. All have been well received. He’s a superb storyteller and his writing has left behind its early, occasionally obvious self-consciousness. Increasingly, it achieves the disarming adeptness and apparent simplicity of Hemingway, whose influence Winton acknowledges. Immensely readable, this fiction, like Robert Drewe’s gains its force from the tension between the spare prose surface with its deliberate understatement and the fullness of meaning within it. A typically sensitive McPhee Gribble publication reproduces this tension, leaving nearly a page blank before the few lines of type that begin each chapter, and that spatial tension recurs within chapters in the small gaps between sections.

Read In The Winter Dark at a sitting, preferably alone, with the darkness outside. It calls up night terrors and doesn’t dispel them. As irresistible as an overheard confession, this novel has that nostalgia for a lost innocence so typical of Winton’s earlier writing. Taking some comfort in the ‘fact of the sunrise’, Maurice recognizes why. ‘People used to take it as a sign that everything was under control’. Now, however, this is no longer possible, and this narrative doesn’t fall back into comfortable compromise. Now, Darkness is all.

Comments powered by CComment