- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

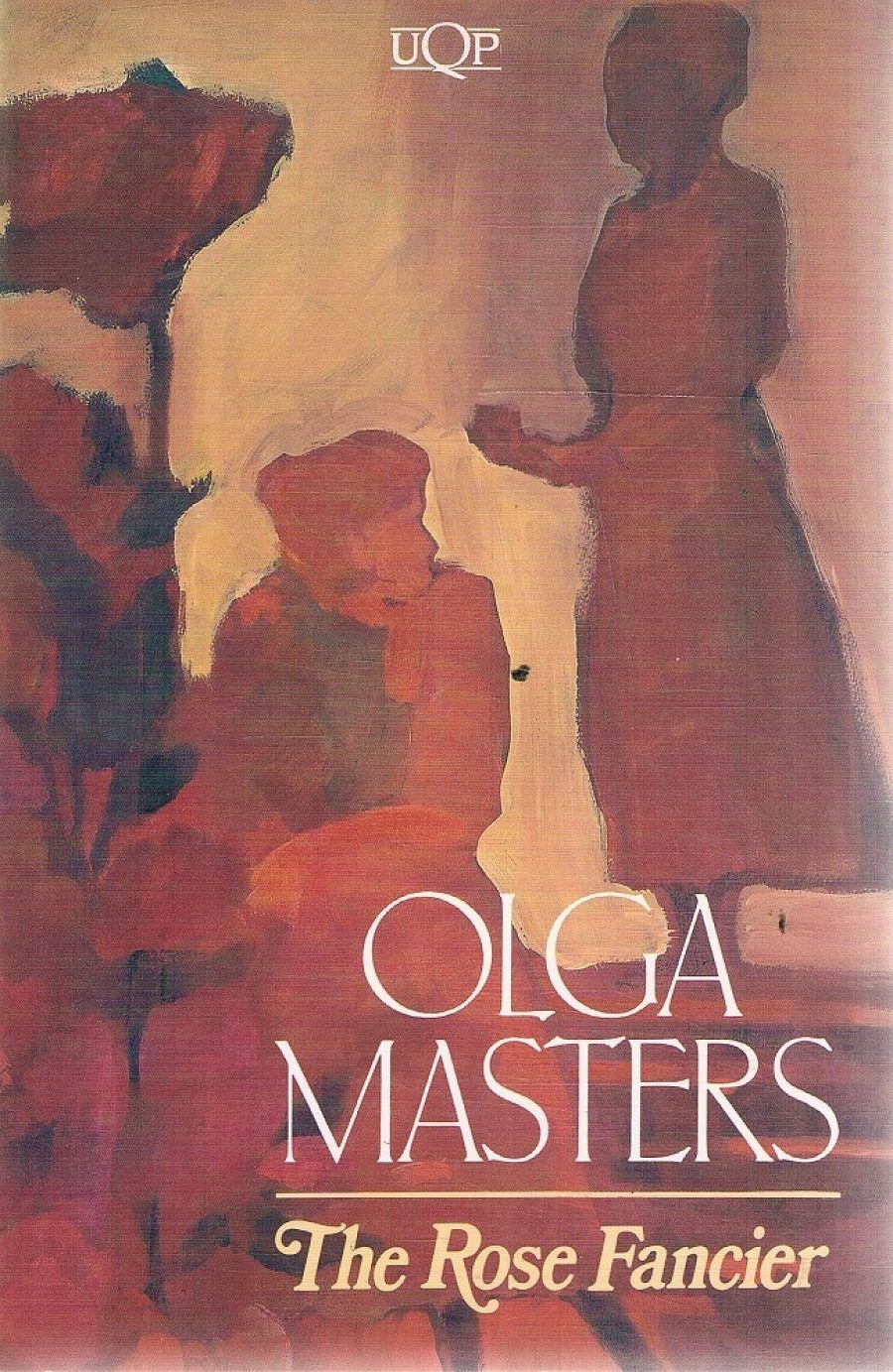

- Custom Article Title: Don Anderson reviews 'The Rose Fancier' by Olga Masters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fine brushwork on a small canvas

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I first made the acquaintance of Olga Masters’s writing some years back when a judge of the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, for which her collection of stories The Home Girls had been submitted. I was immensely impressed by the control, passion, and implicit violence of the stories, and was of the impression that the book should win. But another judge, of considerable seniority, carried the day with the opinion that all the stories in the book were ‘at the same pitch’. It seemed to me at the time, and still does, that her objection could equally be levelled at, say, Flannery O’Connor or Dubliners, but that’s water under the bridge.

- Book 1 Title: The Rose Fancier

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $19.95 hb, 144 pp

Olga Masters, who began her career as a fiction writer very late, died in 1986. This collection of seventeen stories is a posthumous testimony to her power. At the time of her death, her publishers tell us, she had chosen the book’s title, outlined the sequence of stories, and prepared final drafts of eight stories. Nine more were still in draft form. Editorial alterations to the nine early drafts were restricted, as much as possible, to the kinds of corrections Masters herself had approved in the editing of previous books. Some scenes were clarified, but little was deleted and nothing added. Such a practice gives a whole new meaning to such currently fashionable notions as the ‘death of the author’ and the ‘myth of presence’.

That appalling Englishman, Howard Jacobson, who might best be described – had Suzanne Kiernan not immortalized him as ‘the kind of writer who gives smut a bad name’ – as a cuckoo that, having been rudely ejected from the nest it has invaded and fouled, returns periodically for another gluttonous gulp at its foster-siblings’ food, took the liberty of passing summary judgement on Olga Masters in the Times Literary Supplement. He opined, of her novel Amy’s Children:

All human heart drama played out on a flat board by characters whose very names defy you to be interested in them … and written in the prose style of a town map.

Amy’s parents are Gus and May Scrivener. What did Jacobson want them to be called? Paul? Ursula? Howard? Olga? Bartleby? Perhaps he would have done better to consult a register of births in Australia in the earlier decades of this century than a town map, if indeed he consulted the latter. (And one cannot imagine that he did, given his denigration of Gerald Murnane). Jacobson should consider himself lucky that one of Masters’s sons did not come round and drop a scrum on him, or that another didn’t do a job on him on Four Corners.

Masters was not unaware of the small canvas on which she was working, a small canvas that might be said to be the choice made by short story writers. She told Jennifer Ellison:

I learned a lot about human nature, and human behaviour, as a journalist. I worked on small papers, and you’d go out for a story and it wouldn’t be much of a story but you’d make it into a story. The lesson there was that there is more in life, more in situations, than meets the eye. The deeper you dig, the more you find.

Again:

If you write about life, you write about life, and it was a dull little corner of the world [where she conceived Loving Daughters), and there is no changing it. You can’t make drama where drama does not belong … They are sleepy villages but still there are human beings in those villages and they’re entitled to their story.

If you recall Patrick White’s injunction to discover the extraordinary within the ordinary you will perceive the justice of Masters’s choice. She is concerned to render the small dramas, the ‘small moral decisions’ (Eric Rohmer on his films) that are crucial to otherwise uneventful lives. She renders crises in the lives of the forgotten of the earth, their ‘bones from insult to project. ‘She writes about bush families, dying towns, isolated children, aged couples, single parent families, inter-generational incomprehension. She writes, in short, about the lives of girls and women.

To return to that parenthesis about Eric Rohmer, that master of the short story as a cinematic genre. Gene Hackman is given a great if cheap line in Francis Coppola’s film The Conversation: ‘I once saw an Eric Rohmer film. It was like watching paint dry.’ There is sense in which reading a fine, rigorously disciplined, subtly rendered, and scrupulously edited short s tory is like watching paint dry – on a small canvas. But that is to be taken as a compliment.

Masters’s story ‘Inseparable’, about a mother and daughter and the intrusion of a man into that inseparableness, manifests all her strengths. It has all the qualities itemised in the last paragraph, in addition to which it resonates, long after one has read it. It resembles nothing so much as an oriental paper flower which, dropped into the pond of one’s consciousness, expands and expands. It is a story the structure and drama of which Flannery O’Connor would have appreciated, though she would have given it an eschatological dimension (all her stories, she said, were about the action of Divine Grace). Masters is resolutely secular. Again, while Masters hardly shares O’Connor’s gothic intensities, there are times – in the title story, for example – when she trembles on a Southern edge (there are Faulknerian echoes in this story).

Like many women writers, Masters (who shocked younger women authors by revealing that she washes her husband’s and sons’ football gear after her own day’s work) has a fine eye for domestic detail. Her tabulations of the minutiae of daily life are not merely important social history, but crucial to the rendering of the lives of her ‘sleepy little villages’.

The last of the potato was being scraped off the plate and piled on thick slices of bread to be eaten with green tomato pickle, very tart because sugar was a precious commodity used sparingly even for jam and forbidden in tea.

It is to Olga Masters’ great credit as a realist of the emotions, as a realist of the sleepy little villages, that she never tries to suggest that her characters are ‘village-Hampdens, … with dauntless breasts’. Her refusal to extrapolate from the local, to strain after wider significance, to allegorise, is her, and the short story genre’s, central strength.

Howard Jacobson, in calling at the end of his TLS conspectus for a moratorium on the Australian short story, displays not merely his inability to read (Olga Masters and, more egregiously, Helen Garner) but his ignorance of Australian literary culture and of the nature and achievements of the short story as a form. This is not surprising in a cultural cuckoo, in a Leavisite (or is he now a post-Leavisite?) who would be obliged, like the Master (Frank Raymond, not Henry) to valorise the upper-case Novel over all other literary modes, or in one who writes the kind of (distinctly lower case) novels Jacobson writes. It’s just that we shouldn’t pay any heed to him, not even if he is given the institutional endorsement of the TLS (pardon me, Stephen Knight).

Comments powered by CComment