- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Staining the Wattle is the fourth volume of a series edited by Verity Burgmann and Jenny Lee collectively entitled A People’s History of Australia since 1788. People’s history, as understood by Burgmann and Lee, is not popular history, that is to say history written to be of interest to the general reader. This book actually makes very dull reading. Nor is it exactly, at least to judge by this volume, social history, that is to say history dealing with the lives of ordinary people. This book is about politics. People’s history, as understood by Burgmann and Lee, seems, rather, to be ideologically useful history; history as a weapon of social change, as a means for the unmasking of the forces of oppression which have shapes, and for the glorification of the forces of progress which have struggled to reshape, Australian history.

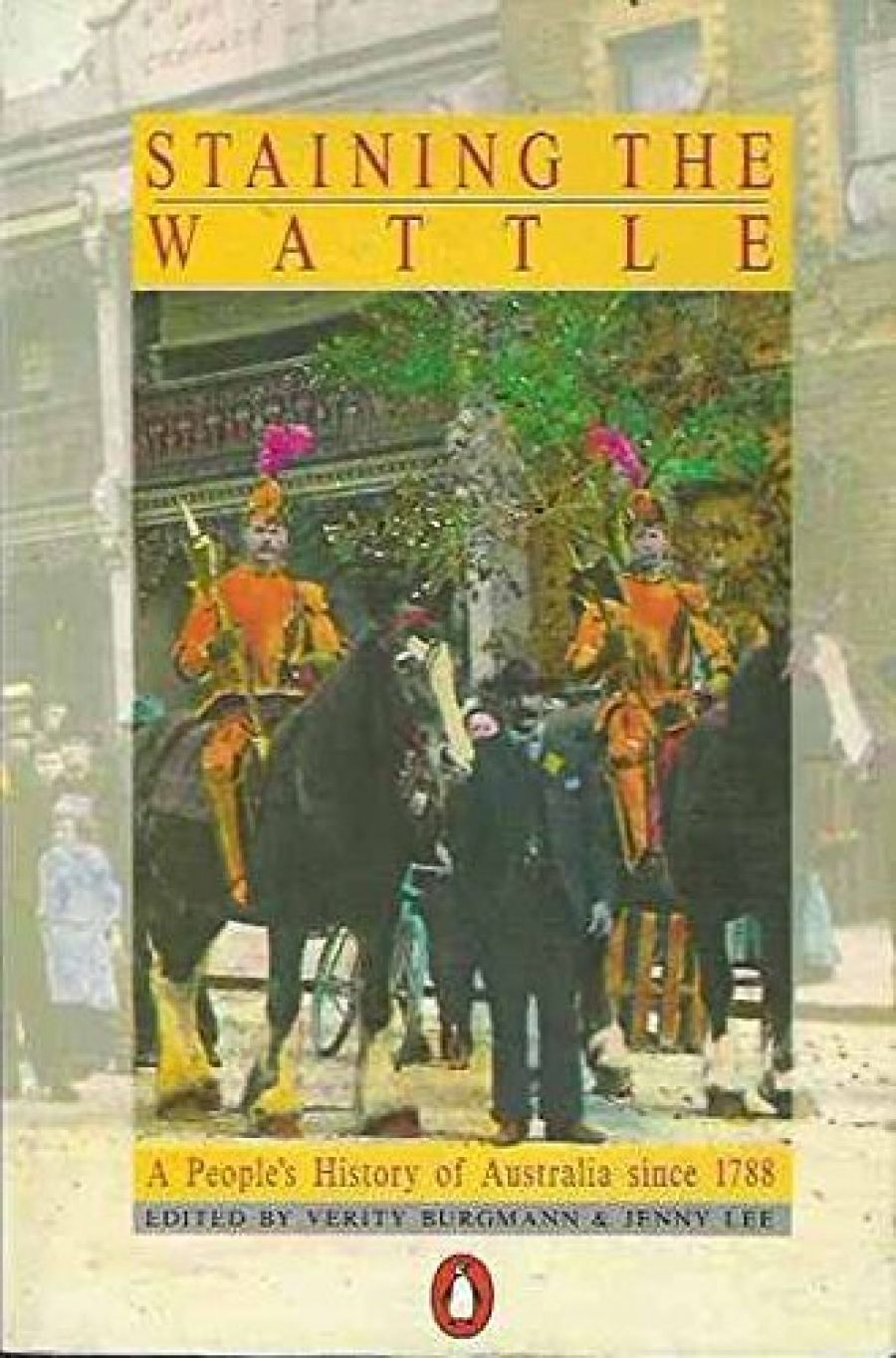

- Book 1 Title: Staining the Wattle

- Book 1 Subtitle: A people’s history of Australia since 1788

- Book 1 Biblio: McPhee Gribble/Penguin, 308 pp, $16.95 pb

The collective view of Australia presented in this volume is exceedingly bleak. We are told that Australia was ‘the first police state’; and here ‘state terror could be practised without the faintest suggestion of impropriety’; and that ‘what has happened in this country since the arrival of the First Fleet is one of the greatest crimes ever committed in the history of humanity’. The editors of The People’s History themselves describe the two hundred years of white settlement as a ‘brief, nasty interlude’. One essay quotes a trade unionist who, in 1891, spoke of Australia as a ‘tolerably complete working model of hell’. This is, roughly speaking, the vision of Australian history conveyed in this volume.

If there is a .general ideological thrust to The People’s History – which comprises many short essays, of uneven quality and style, on disparate themes – it is crude Marxism. For the past two hundred years, we are told on a number of occasions, a monolithic but cunning entity, sometimes called the state and sometimes the ruling class, has devoted its energies to oppressing the working people.

One contributor writes:

Over the years,

Robert Manne

Verity Burgmann and Jenny Lee (eds)

Staining the Wattle: A people’s history of Australia since 1788

the Australian ruling class used a variety of tactics against potential threats. They have defended their position and privileges by the use of force ... They have won over influential people from within the labour movement and fostered division among workers; and, when they had no other choice, they have made strategic concessions to working class demands.

Against this exploitation, small bands of brave souls – revolutionary socialists, feminists, peace activists, environmentalists, gay liberationists – have waged an unequal struggle. These groups form the collective hero of the volume. Those who did not struggle against ‘the system’ and were not oppressed by it – the farmers, businessmen, architects, soldiers, scientists, public servants, judges, and politicians – are collectively dismissed as the servants of capitalism and privilege. The contributors to this – volume are, of course, aware that extreme radical groups have at best played a marginal role in our history. Accordingly, a melancholic mood of defeat pervades the whole enterprise, which is captured in the chapter headings: ‘Only the Chains Have Changed’; ‘Divided We Fell’; ‘The Beat of Weary Feet’; ‘A Hundred Flowers Faded’.

The ordinary working people are by no means the heroes of this volume of The People’s History. If the truth be told, the people here seem altogether too passive, conservative and gullible, only too willing to be duped into fulfilling the role of the oppressed assigned to them by the masters of capitalism and the Labor political leaders who have, time and again, betrayed them. When Alastair Davidson tells us that the constitution of 1901 has kept ‘the population beavering away in an orderly manner, oblivious to the possibility that there might be other ways of using their time and space’, he speaks with that accent of condescension characteristic both of this volume and of the socialist intelligentsia in general. This collection glorifies The People; it is rather dissatisfied with the people.

The contributions to The People’s History are not only ideological (which limits the persuasiveness of even the interesting empirical essays, like Heather Goodall on land rights and Patricia Grimshaw on feminism) but also provincial. The world of experience outside Australia hardly exists. In the chapter on the anti-war movement in Australia, Chris Healey, for example, claims that Germany by 1939 had invaded Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland. Hungary? How can an author writing about the issues of war and peace in our century be so ignorant of the basic facts of international history? In the chapter on the labour movement, Verity Burgmann and Stuart Macintyre praise the ‘internationalist’ currents of the Left in the 1930s – by which they clearly mean the Communists – and contrast these with the ‘sorry record of bigotry’ of the Labor ‘nationalist’ mainstream. They do not seem concerned that they are praising precisely those Australian Leftists who worshipped Stalin, a mass murderer whose crimes equalled those of Hitler. Do they really not know that the ‘internationalism’ of the Comintern was Russian nationalism at one remove and that the internationalists they praise gave support to the Nazi-Soviet Pact?

Barry York – to come closer to our own age – provides an enthusiastic evaluation of the movement in Australia against involvement in the Vietnam War. He does not seem to be alert, even at the edge of his consciousness, to the moral complexities of his subject. The antiwar movement in the West was critical to the victory of the communist forces in 1975. Since their victory the Vietnamese people have suffered terribly, with the re-education camps and one million boat refugees. Is all this of no significance to the historian of the ‘anti-Vietnam’ movement? Or again, Andrew Moore is hopeful that the experience of the Hawke government ‘will finally lay to rest the illusion that there can be a parliamentary road to socialism’. Has he really not noticed that in the contemporary world the quest for liberation from dictatorships of the right and left – from Chile to Poland – has inevitably taken the form of a struggle to establish a parliamentary form of rule? How can he so lightheadedly look forward to the overthrow of parliamentary government in Australia? Perhaps he is merely pretending.

Herein lies a clue. Apart from one or two non-academic contributors to this volume (and, in particular, in the piece by the black activist, Gary Foley, where the ideological anger is genuine), the tone of this volume is bland, the revolutionism comfortable. Even the title of this collection, Staining the Wattle rings false. Since Henry Lawson made his prophecy, political blood has not stained the wattle in Australia. As the son of parents who fled from Nazi Europe, I am incapable of seeing this as a matter for regret.

Comments powered by CComment