- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It seems strange to describe Diamond Jim McClelland as, really, rather an old-fashioned man. Few septuagenarians have anything like his energy, his forthrightness, his optimism, or, most of all, his receptivity to new ideas. But if there is a continuous thread in his extraordinarily full and complex life, it can probably be best summed up as a very untrendy, passionate commitment to morality. The catch is that his ideas of what constitutes morality – or at least what is the best way of achieving it – have gone from here to there and back again.

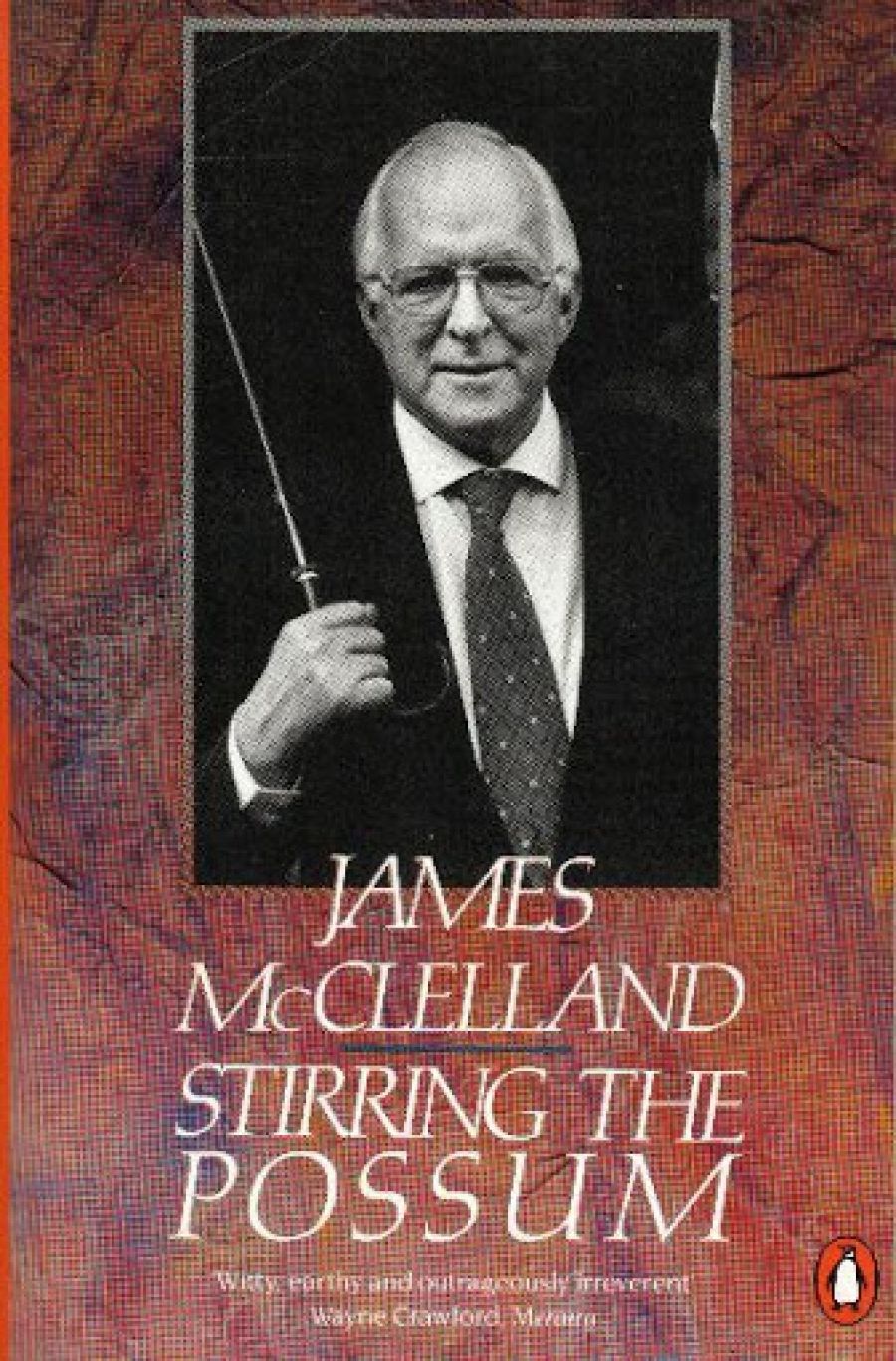

- Book 1 Title: Stirring the Possum

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, 261 pp, $29.99 hb

An unkind critic would say that Diamond Jim had had more ‘isms’ than most of us have had hot breakfasts, and that a number of them – particularly the later ones – were suspiciously convenient for his career path at the time. But in fact this would be neither fair nor true. At various times in his life it has been possible to label McClelland left or right, socialist or elitist, libertarian or authoritarian. But, as he points out himself with a touch of complacency, none of the labels really fit. He is genuinely unclassifiable, which is what makes him such an interesting and engaging – if at times infuriating – political figure.

His idiosyncratic morality explains much of the contradictory nature of the man. He is superficially gregarious: Diamond Jim surrounded by his mates of the moment is an awe-inspiring sight. But the mates seldom live up to the standards McClelland sets for himself, and by implication, for them. His split with John Kerr – ironically, one of the people who suggested he enter parliament in the first place – is of course legendary. But the wayside of McClelland’s life is littered with the bodies of other one time close friends and important influences whom he has, in his own view at least, outgrown. His Trotskyist mentors, his right wing unionist colleagues, his political benefactors – these days there are few kind words for any of them. Gough Whitlam escapes more or less unscathed, although his political judgement is condemned for the ministry he desperately reshuffled towards the apocalyptic end of his government. Bill Hayden receives an approving nod. Neville Wran is seen as something of a sell-out. The current government is dismissed as lacking both principle and style – the latter, in a funny way, being somewhat more important than the former. McClelland marks his report cards hard.

So in the end, what are his consistent criteria? Intellectual rigour, certainly; he claims to have read the whole of Karl Marx’s Capital twice (something few, if any, Australians can have managed) before parting company with communism. A desire for a more equal society, perhaps: the McClelland family weathered the depression better than many, but his social reforming zeal has been a constant, although it has gone in many different directions. The pursuit of excellence also comes into it; despite his nickname, McClelland has and time for drones or fools.

But one feels that in the end McClelland, though a compulsive joiner of ideologies, is really more interested in being his own man than in changing the world. His philosophy these days at least seems to lean more towards John Stuart Mill than to Marx and Engels. He has called his autobiography Stirring the Possum, but it is hard to avoid the impression that if the possum is too lazy or stupid to respond to the stirring, McClelland will desert it for another piece of fauna which reacts in a more satisfactory manner.

The last chapter of the book provides another insight into his approach: we need geniuses, but even more we need people who are prepared to embrace a cause. What we are not told is why McClelland’s causes are a better hit parade than others. To him it may be self-evident: certainly his autobiography, self-deprecatory though it often is, makes each of his leaps of faith seem both logical and inevitable. To those with more self-doubt (as opposed to intellectual scepticism) the choices may be less clear.

Which brings us back to the old fashioned aspects of this most energetically modern of thinkers. Our finest historian, Manning Clark, has written that ours is the first generation in history to have grown up without the idea of God. McClelland, with all respect, is really a member of the previous generation. He is now a convinced atheist (he would never be so mealy-mouthed as to proclaim himself an agnostic) but throughout his life he has had a relatively untroubled belief in God-substitutes: his causes. He has never been unmotivated or despairing, and seldom bored. Perhaps his brief time in the Whitlam government was the only period in which his didactic refusal to compromise with what he saw as cowardice and incompetence was a real disadvantage. In Australian terms, Diamond Jim was never really cut out to be a politician. A philosopher king, perhaps; but Australians have never really taken to the idea.

The story of Diamond Jim, the boy from Richmond whose ambition, as he once said, was never to be rich, but simply to be ‘not poor,’ is at one level a success story, at another an enticing piece of social and political history, at another a disturbingly honest account of a man whose beliefs never quite fitted the world around him, and finally something of a morality play.

It is also superbly written and a bloody good read – as one would expect. It is hard to think of any other contemporary politician who could produce a work of such passion and wit. If Diamond Jim did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him. Let’s hope that someone does, in the very near future. Now, more than ever, we need a few like him in parliament – if only to stir the possums.

Comments powered by CComment