- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A crucial clue is given right at the beginning in the form of a lavender plant punningly sent to Claudia Valentine, our detective heroine. Like just about everything else in the novel, it turns out to have been put there by the novel’s Mr Big, Harry Lavender. And finding out the extent of his influence is what keeps us going through the back alleys and one way streets, more often than the smoothly flowing highways, of a clever detective narrative.

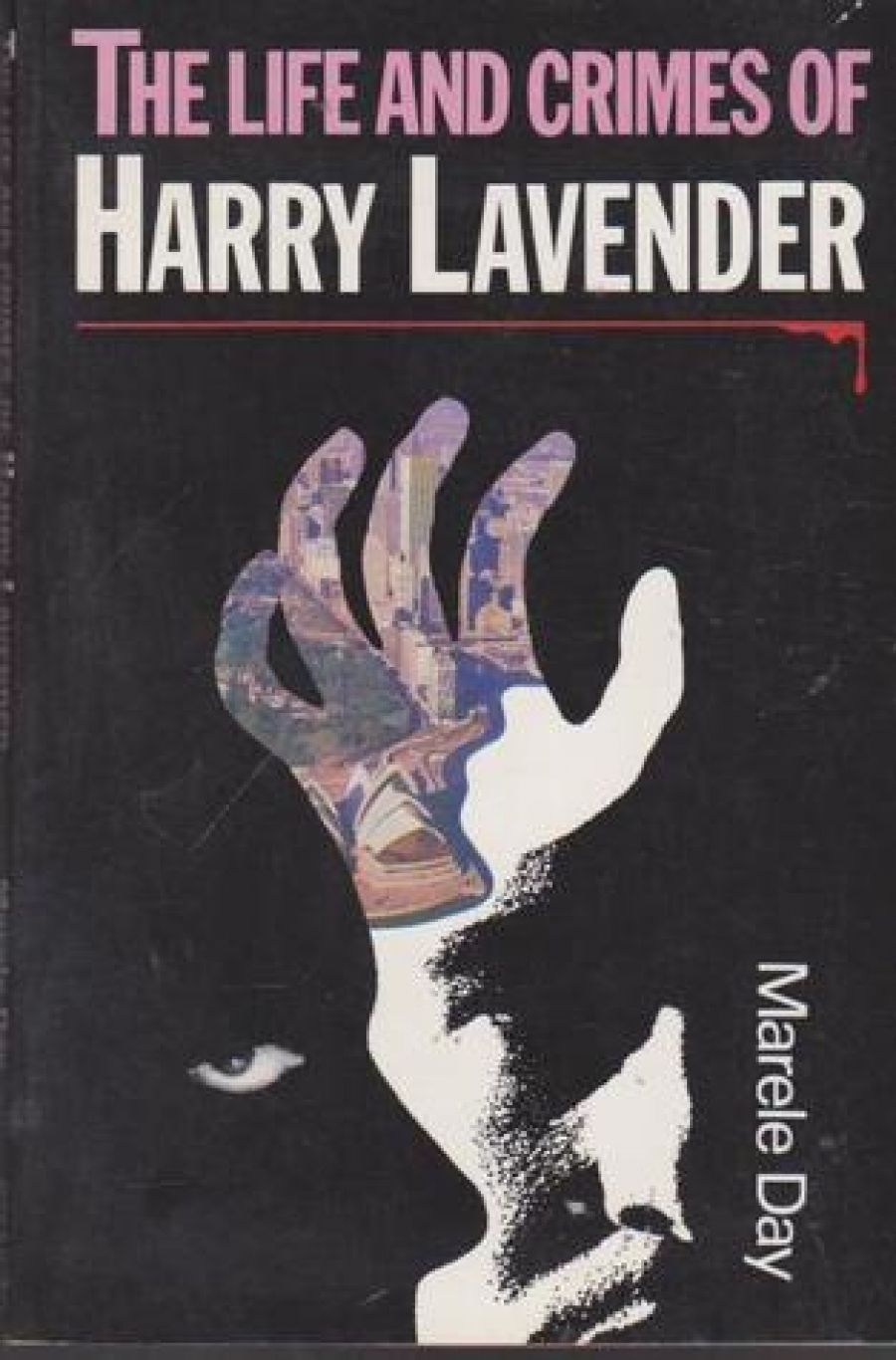

- Book 1 Title: The Life and Crimes of Harry Lavender

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen and Unwin, 159 pp, $10.95 pb

Well, this is corruption, but it’s also important that the imagery begins in a remembered scene from a movie. Sydney is presented here as a post-modern city, made up of reflecting facades and surface images, so that doing private detective work in it is like doing puzzling research in a library. Day shows without needing, explicitly, to state that the city is like a text. Leaming what’s going on requires cracking the code, which is not obvious for it works on what seem to be obscure connections in the manner of a cryptic crossword or a computer. Indeed this latter provides not just the central puzzle but a central image. Its bloodless connections have taken over all aspects of organic systems, invading hearts, even Claudia’s, so that eventually she finds she was working cryptically for Mr Big, without knowing it.

Claudia is a modern gal, working hard for a living. She was young in the mid-seventies when ‘like everyone else ... we were going to change the world. Blow it up.’ Now she suppresses her emotions, and finds there’s not much more to do than ‘chip away at the structure.’ The problem is that modem crime and its legal allies, and the technology that supports, it, have made recognising these structures for what they are well-nigh impossible.

I won’t tell you all the details of Claudia’s adventures, because I want to encourage you to read this book yourselves. But I will say that The Life and Crimes of Harry Lavender has all the classic ingredients of a Raymond Chandler style mystery. There is a murder that’s not seen as such, a warning moral in Claudia’s past, a missing manuscript (we are treated to extracts from this interspersed throughout), a neurotic heiress, drugs and thugs, car chases and some pretty good fights, seedy video arcades and wealthy mansions. And a continuing mystery – why is it that despite bruises, bites and neardrownings, Claudia gets off so easily?

There is, however, one important difference, which is presented as a fact for the story but which is also taken up structurally, so that most of the novel is organised around the concept of ‘reversal’. Claudia, unlike Philip Marlow, is a woman, so the gender codes of detective fiction are topsy-turvy. Accordingly, her contact in the police force is a woman. Her possibly untrustworthy lover is a man. And when Claudia wants to talk to a female suspect privately, she takes her to that hallmark of designer feminism, the businesswomen’s sauna. But don’t be too alarmed – Claudia herself lives down-market, above a decaying pub!

Day achieves much more than merely imitating a masculine style. Like an expert in a computer program, she takes the detective story over. In this way her work is in the tradition of other feminist detective novels, like those by Barbara Wilson, Mary Wing, Jan McKemmish or the V.I. Warshawski stories. Of special pleasure is the language which is full of sardonic and acute observations. The detective shrewd-talk is applied to Sydney in ways which complement and extend our usual thinking. Sometimes there is parody. We get not just an urbanely weary ‘The sea was deep blue now, the colour of a cigarette commercial’ (about Bondi), or a capitalist-inspired image of helpless workers, ‘Crane drivers in hard yellow hats eat sandwiches, their legs dangling down the concrete canyons’, or a sophisticate’s ‘Moderation in all things, including moderation’, or the outrageous feminist humour of ‘strangler[!] figs, their aerial roots hanging lush like underarm hair,’ but, during a fight, ‘I heard the words hut I also heard between them’. Day here refers not just to the necessary paranoia of a detective’s methods of thinking, but also to the methods needed to decode post-modern systems. These involve to a degree identifying with, through being fascinated by, that system.

This is not just a good read, though, for the novel is connected quite securely to at least the ‘reality-effect’ of a real world system. Claudia find that money and crime, as they always have in Australia, control almost everything. ‘The effect [of Royal Commissions] is the protection to gets more expensive.’ (Not a bad way of thinking about the Fitzgerald Inquiry in Queensland.) Day gives us nice references to doctors who have ‘baby grand pianos in the waiting room’, but also provides plausible explanations for her novel’s Mr Big by locating the source of capitalist greed in recent history, here the horrors of Poland under Nazi Germany.

What hope is there? Detective novels, which show individuals battling in isolation against, usually, contemporaneous systems aren’t centrally concerned with constructing future possibilities. Day does not raise, however, the healing effects of ‘simple, human values’, for the city and its controllers have no heart and neither, as a result, do many of its people. But is it ever really possible to return to a pre-lapsarian, nostalgic past from a position of experience? Right on the point of solving the mystery, Claudia contemplates her home which now has become ‘Harry Lavender’s city’.

My city was the most beautiful harbour in the world, a childhood of open doors, of ocean breezes on hot summer nights, of passionfruit and choko vines growing in the heart of a city without pollution, the innocence of a time past before the stench of Lavender. But the stench has always been there, I just hadn’t smelled it till there was no place left that didn’t reek of it.

The novel suggests it isn’t.

Comments powered by CComment