- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the wake of the spectacular collapse of Rothwells and unsavoury revelations about Western Australian entrepreneurial enterprise, it is very apposite for Penguin to have republished Nick Hasluck’s 1980 novel, The Blue Guitar. This novel, as relevant now as nine years ago, deals with the world of entrepreneurship with its illusory money, fast talk, and duplicity. It is a world of the corrupt and the corruptible, where principles and moral certainties give way before glib notions of innovative thinking and flexibility.

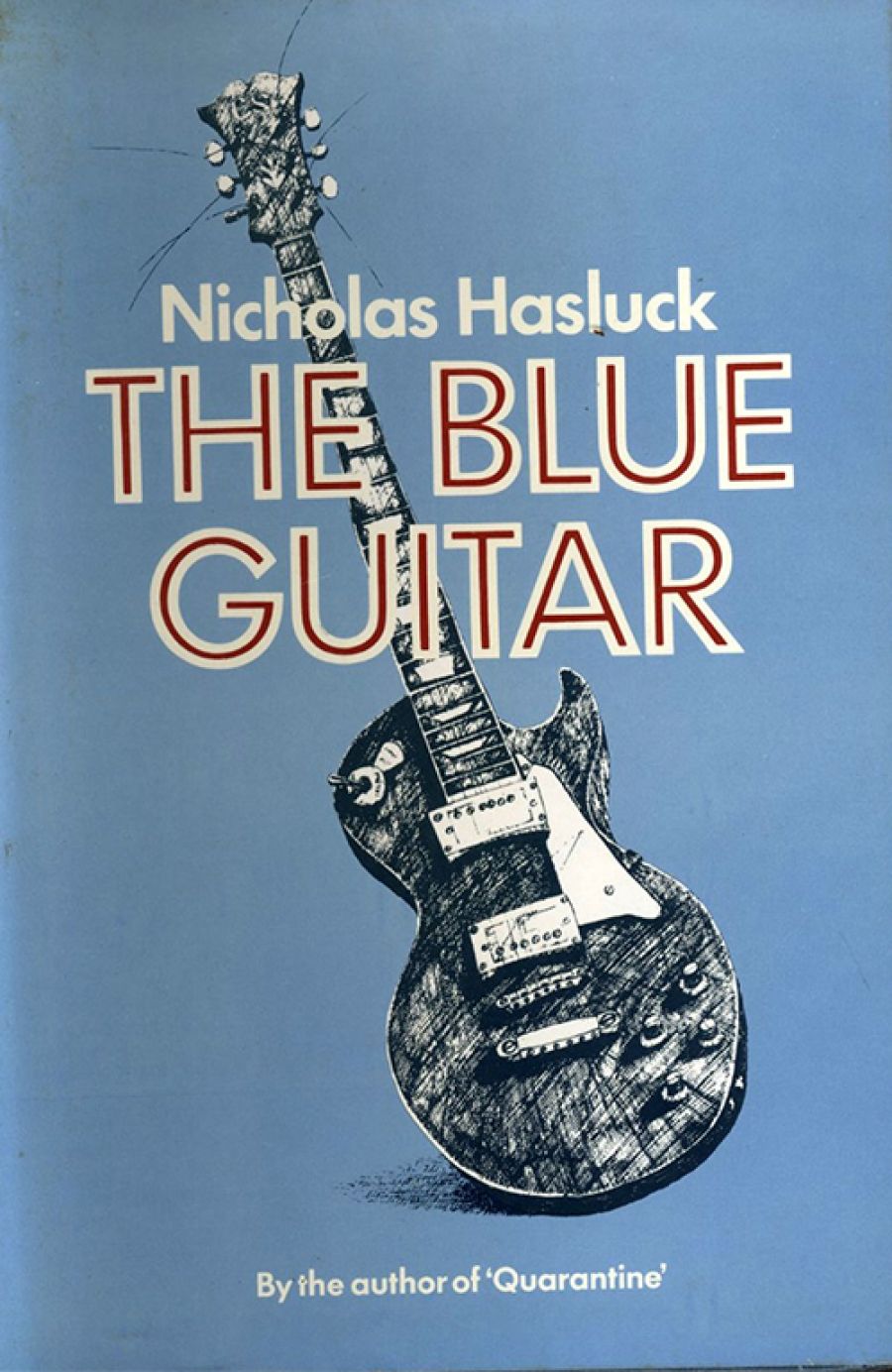

- Book 1 Title: The Blue Guitar

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $11.99 pb, 206 pp

In the wake of the spectacular collapse of Rothwells and unsavoury revelations about Western Australian entrepreneurial enterprise, it is very apposite for Penguin to have republished Nick Hasluck’s 1980 novel, The Blue Guitar. This novel, as relevant now as nine years ago, deals with the world of entrepreneurship with its illusory money, fast talk, and duplicity. It is a world of the corrupt and the corruptible, where principles and moral certainties give way before glib notions of innovative thinking and flexibility.

Hasluck’s protagonist, Dyson Garrick, self-styled promoter and developer, is a babe in this wood, despite his flair and his capacity ‘to push hard for something worthwhile, to take a shortcut now and then’. Dyson fancies himself as a sharp operator, but he is also something of a sentimental idealist. Having got hold of a promising invention, a transistorized guitar, he is overwhelmed with the vision of a new generation of communal togetherness, of rescuing youth from boredom and self-abuse:

Dyson felt inside him, like a living thing struggling toward the sun, a certainty, a sense of exultation, that this instrument, this almost bizarre curio, was going to work, that he could carry it right through, that there was something about it people would take hold of and insist on having.

Dyson is a likeable character: flamboyant, fun-loving, and funny. He is also fundamentally flawed. As a passionate devotee of the cult of entrepreneurial success, he is willing to sacrifice his peace of mind, his personal relationships and, inevitably, his moral integrity. It’s the hype and adrenaline rush that get him, which he likes to compare to the thrill of the free fall: ‘You’re just about flying. You can do virtually anything.’ Everything, that is ‘except go back up’. Like the smart boys on whom he models himself, Dyson hustles from one project to the next barely ahead of the creditors and the government regulators. It is an activity not dissimilar to the wheel of perpetual motion he is shown by his hapless partner: ‘A wheel that spins without depending on any external source of power ... not necessarily a fraud, my friend, but another riddle. One of the great riddles.’

But as the regulators and the creditors close in, Dyson finds it is not idealism but self-interest and duplicity which keep the wheels of enterprise spinning. At the end of the free fall, he has to acknowledge, is a body in a field of mud; and when it comes to the crunch he will cheat on his partner to save himself. Why should he expect something different? As his father says: ‘That’s what businessmen do ... Isn’t it? Rip it off each other.’

It is also Dyson’s father who points out that: ‘Guitars can be turned into art. Not just projects.’ He refers in this instance to the poem by Wallace Stevens which gives the novel its title:

The man bent over his guitar,

a shearsman of sorts. The day was green.They said, ‘You have a blue guitar,

you do not play things as they are’.The man replied, ‘Things as they are

are changed upon the blue guitar’.And they said then, ‘But play, you must,

a tune beyond us, yet ourselves,A tune upon the blue guitar

of things exactly as they are’.

For all his optimism, his energy and genuine goodwill, Dyson Garrick is not a man to play ‘things exactly as they are’. He has his simple dreams of a more benign, communal life, but his infatuation with fast money and dubious deals leads to the reality of lonely self-loathing, and a world created from junk: ‘all of it pushed up bleakly into crude, serrated skylines, the air within the labyrinthine canyons dank and lifeless; the feeling of it, stifling, suffocating, oppressive’.

The Blue Guitar is in many ways reminiscent of Robert Penn Warren’s classic novel of political corruption All the King’s Men. Like Warren’s flawed hero, Willie Stark, Dyson Garrick believes that he can use corrupt means for idealistic ends, but is inevitably corrupted and destroyed by the forces he sought to use. Hasluck has written a vivid account of the world of shady deals and dirty tricks, but, disappointingly, that is the only world he gives us. In Warren’s novel, the fall of Willie Stark is the vehicle for the moral redemption of the narrator, Jack Burden, and descriptions of the tawdry backroom politics are balanced with philosophical passages of great lyric power. In The Blue Guitar, there is no hint of redemption, no character capable of transcending the venal impulse of the age. I found this a major problem with the novel, since it tended to leave an unpleasant aftertaste. It may be awfully old fashioned of me, but like the unseen audience in Wallace Stevens’s poem, I wish to exhort the novelist: ‘But play, you must, a tune beyond us, yet ourselves.’