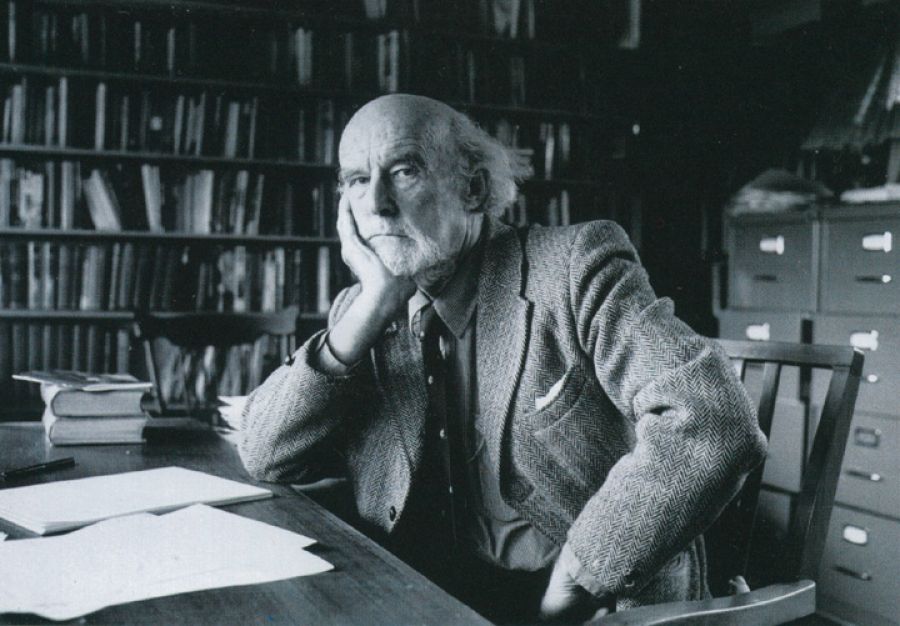

On 27 May, 1991, Manning Clark, Australian historian extraordinary, was buried from Canberra’s Roman Catholic cathedral by his friend the Jesuit Dr John Eddy, assisted by Professor Clark’s brother, an Anglican canon, and with the participation of his sons. After his death on 23 May, ABC national television had broadcast an interview of 1989 in which Clark had responded to the question of whether he believed in an afterlife with a firm no – to which he added that he saw merit in the response of a Mexican academic encountered twenty years before. On that matter, he harboured ‘a shy hope’. It is a smiling happy phrase, contrasting with the dark fear of future judgement that bedevils so many of the Protestant characters with which he populates his histories. And it was a qualification in harmony, not only with his occasional visits to the church that farewelled him, and earlier St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney and a multitude of European churches, but also with the ambivalence and perplexity at the heart of the man and his work. Some would call it contradiction or even evasion, but the native Australian sense of having a bob each way is sound policy, and Manning was not one for some pointless cremated affirmation of the kingdom of nothingness when he could have a touch of Catholic ritual and grandeur.

The run of banal humanist obituaries that sought to create a Clark in their own superficial image and likeness raises the question of how much the standard public figures had either encountered or understood Clark the writer. Fame has its price. Such patently mindless veneration also raises the question of the distinction between Clark the performer, the public man, the guru, the once fiery prophet of doom (more recently of happier times), and Clark as serious historian. A cynical ABC commentator observed he had never encountered anybody with a full set of the Histories. I overheard at a Clark launch a beard explaining that he had invested in a signed set to give to his infant (Aaron or Sarah – something Clarkian biblical) on his/her twenty-first birthday – history as antique value-gathering artefact.

All of this is common and predictable with living legends and national treasures; Manning Clark himself became a collectable to be sighted as much as to be cited. And there can be no doubt he was very well aware of – to put the situation at its most inert – that kind of attention.

But anybody who has actually read Clark must be struck not only by the brooding darkness and ambiguity of the vision but, even more basically, by its puzzlement and uncertainty. This is squarely declared in the very titles of his autobiographies, The Puzzles of Childhood and The Quest for Grace, not to mention In Search of Henry Lawson.

Another angle to unsettlement is proclaimed in the short stories, Disquiet (1956). Swings of ideological enthusiasms and allegiances were evident in not only books but also hats and dress. Meeting Soviet Man (1960) was accompanied by a phase in which the author appeared in Russian hat and peasant shirt. To apply the interpretative documentary scrutiny the author himself devoted to painted historical portraits, what is the meaning (if any) of the dust-jacket author photographs on the Histories? All bare-headed and chronologically aged; looking modestly down on Vol. 1, challengingly up on Vol. 3, pleasantly to the side on Vol. 4, changing by Vol. 6 to the Kahan line drawing in which timeless art thereafter prevails. And the volume titles; plainly descriptive (‘From the Earliest Times ...’) up to Vol. 3, then the full biblical fortissimo of Vol. 4, ‘The Earth Abideth Forever 1851–1888’, as the work took on its full character as an Australian religion-secular bible and book of common person’s prayer, with prefatory quotes swinging from Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky in Vol. 1, to the Bulletin and Cardinal Moran (‘it is an age of ruins’) in Vol. 4. (The succession of broad-rimmed hats was not, strangely, R. M. Williams Akubra, the style more a blend of fundamentalist American preacher with a touch of historical off-to-the-diggings. Reliable authority has it that at least one was made for him personally in Texas by John Wayne’s hatter.)

At the same time the volumes were tending from the very personal to the extremely idiosyncratic, so that the last (Vol. 6) covered the unusual period 1916–1935, with a six-page epilogue to 1945, and explains in its preface, ‘Like its predecessors this volume does not pretend to be a general history of the period’ – a disclaimer that appears to openly contradict the title A History of Australia Volume VI. Or does it?

The Preface continues, ‘it concentrates on those events which have helped to make Australians what they are, and aware of what they might be’. What they are? Or does he mean what they were? For, in a last television interview, with Maggie Tabberer of the ABC Home Show, Professor Clark explained his decision not to extend his history past 1945 by saying that he did not understand that recent period. He was, he said, a man of an older Australia. While the latter is true, the implications of the whole remark are disconcerting. Was Clark, the gnomic public commentator on current affairs, making contentious observations on a world he did not profess to understand?

All of this is bewildering, not to say confusing, as is the whole matter of the interaction between Clark the historian and Clark the public figure. Was the confusion real, or his shield against the world and his language to deal with it? The atmosphere of puzzlement and blurring, of generalisation (the straighteners, the measurers), of uncertainty, sustained in unlikely equipoise with dispositions of strong commitment, moral judgement, and passion, was one of the keys to his immense attractive powers. He offered a non-threatening leadership, indeed a sharing, in a strange blend of commitment and non-commitment, proudly old-Australian, humanitarian, radical, ritualistic. He offered, also, a sharing in the hero and villain worship around which his Histories are structured: Parkes and Lawson, Curtin and Menzies, saints or rogues, boozers or wowsers – hard to tell which merits the greater fascination. Or puzzlement. Is this why, in addition to his Labor preference, he, academic and consummate intellectual, became the hero of an anti-intellectual government? Uncertain and questing himself, he could hardly tell them where to go, make them less than comfortable. With Manning Clark one could face the great and serious questions of life in the context of the evolution of one’s own society, and yet step aside from answering them. The questions were enough. Indeed the language of the questions might suffice. At times Clark seems bound and constricted by his own sombre, powerful, Old Testament semantics, driven into a bizarre caricature of himself.

And yet, for all the apparent confusion, the centre so obviously held; that dimension of stability was also part of his attraction. In the age of marital ruins and casual transience which was Canberra’s, here was a local patriot and identity, a man of close wife and family, permanently and obviously loving, secure, warm, hospitable, open to students (I speak from direct experience and observation since 1956). But again, the tensions between life and art. So willing was he to see the good qualities and potential in those whose careers he advanced that his references eventually generated caution, as the fatal flaws and weaknesses in the potter’s clay that he could so readily discern in his parade of historical characters became evident in the living clay he had warranted enthusiastically without defect. The printed fulminations of his Old Testament historical wrath against the past contrasted strangely with the spidery scrawl of his New Testament charity towards this present person or that book.

Some have represented the death of Manning Clark as the end of an era, the passing of both a symbol and major voice of an old Australia which has vanished. Many of those who wept for him were weeping for themselves, perhaps also for the crumbling of the old networks of profession and patronage that operated out of Melbourne and Canberra: the geography of Australian culture decreed that his harshest reviewers were centred around Sydney and its University. This sense of a time at an end, a structure on the wane, is true to the facts of change and mortality, but its friends can be consoled that the size and nature of Clark’s contribution has insured that in vanishing it will not vanish.

However changed or overlaid, its permanence as a legacy is ensured, at least in part, by his recording of his vision of it. That recording lies not only in the History but in those earlier most influential works, the Select Documents in Australian History (2 Vols., 1950, 1955). These were Clark’s first major service to Australian history, a service that opened doors to rooms in the past that many Australians had never before known of, let alone visited. It was in Vol. 2 of the Documents in 1955 that he first used the Dostoyevsky quotation that he repeated for the rest of his life: I want to be there when everyone suddenly understands what it has all been for.’ This is a curious wish; in one sense the expression of the historical observer’s ultimate ambition, in another, a personal identification with commonality in puzzlement. Clark’s usage seems to have been the latter.

Clark’s vision was partial, even of that panorama of old Australia which he had mastered. Nothing untoward in that; it is the historian’s predicament. Elsewhere I have argued that, Australia being an English colony, its historians took – still take – an English view of appearances, accept English priorities, and reflect Protestant value-judgements. The sub-world, for instance, of Irish Catholics had no real existence for historians who wrote from and about the walled gardens of the establishment. The questions they asked, the issues they addressed, the troubles that concerned them have been those of a dying British colonialism, matters of importance certainly, but, despite much of what has been claimed for the Clark approach, at a tangent to the positive issues that have stirred ordinary Australians. And so it was with the publication in 1987 of the final, sixth, volume of C. M. H. Clark’s A History of Australia. Prodigious achievement that it was, this masterwork remains a highly idiosyncratic testament from a once dominant Protestant elite, lamenting its own demise, and taken up with its own present confusions and torments. Professor Clark conceded the shortcomings of his History in relation to Aborigines and women. Its personal idiosyncrasies (as above) are evident from any reading of The Puzzles of Childhood. Indeed, the relationship with the History is openly acknowledged, with his customary ambivalence, in the Preface to the autobiography.

But masterwork it is, no question. We shall not see its like again. Who would have the ambition, the self-confidence, the hubris, the staying power (through a heart bypass), the luck, the sheer intellectual power and historical ability, to sustain six volumes over thirty years? What publisher would back such an enterprise? The new large testaments tend to be cooperative ventures. Let us now praise famous cooperatives? I think not.

More, Clark gave old Australia the epic history it deserves. Like it or hate it, and whatever its shortcomings, it is a treatment on the grand scale which fits the land. So what if at times it is overblown; better that than some prosaic pygmy shrinkage from which we emerge ordinary, diminished.

All this was evident at the beginning, indeed more evident then, given both the conventional narrowness and sterilities characteristic of Australian history in 1962, the tendency in later volumes to dramatise beyond what the material might bear, the author’s repetition of favoured phrases and devices that invited ridicule – and the remarkable revolution in the range and quality of Australian history which paralleled the appearance of Clark’s successive volumes 1962-89. Paralleled yes, but also drew on the new atmosphere and models of approach, the new imaginative and literary freedom, which Clark had demonstrated was possible.

But then, in 1962, it was the shock of the new, to which reactions are always diverse. My own, in Irish Historical Studies, still represent my view of those first volumes:

‘With Professor Clark’s book, Australian history in this, its most extensively studied period, gains a new dimension and stature. The affairs of this tiny convict settlement have at last yielded a meaning and significance beyond the trivial and parochial. In seeing these years of discovery, foundation and early settlement in terms of the clash of great and pervasive ideologies, views of man and the world, in terms of Catholicism, Protestantism and the vision of the enlightenment, Professor Clark, far from enshrining abstractions, has offered an interpretation of Australian history which is absorbingly human and compellingly intelligible. This is immediate, full-sized, thinking and feeling human history, a re-creation of the past.’

My appraisal of Vol. 2 (1968), again in Irish Historical Studies, was that it was even better, greater, but on that occasion I raised some questions which I pursued further with the author in correspondence, questions as to whether later times could carry the vision and style so luminous and dramatic in the ‘Darkness’ which was the first chapter. To quote – and the illustration is famous – the great campaign for the rounding up of Aborigines in 1830 is introduced thus:

‘At that very moment when [Governor] Arthur was brimful with his God, and his yearning that all men might be granted a vision of God’s throne, great madness and folly seized men’s hearts in Van Diemen’s Land.’

Will this approach fit the arid ages of getting and spending that lie ahead? Manning replied that he accepted the point, a response which I think was genuine, not a polite kindness. Whatever, perhaps caught up in the impetus of the paretic semi-religious rhetoric which was to become his stylistic trademark, the ‘great madness and folly’ syndrome, together with the focus on great men, were to obtrude in later volumes where they were far less happy and came under cruel review.

Whatever the professional view of it, and that was, and is, diverse, Manning Clark’s contribution to Australian history is immense. He took it back into the realms of literature, from which it had departed, he resurrected for it a popularity which it had long lost, and he made for it a public reputation, gave it place and significance in the everyday affairs of men and women, a media role, even a brief theatrical exposure. Clark, more than any other person, gave history, as a story, as a communal concern, national meaning and stature. In tone, his gift was uncertain, ambivalent, mixing despair and hope. In a country that had enjoyed its history vacantly, by merely going along for the ride, Manning Clark took serious, often tormented pause. With Dostoyevsky, he did not seem to know what it had all been for, or, if there was indeed a puzzle, what it was. But, to his enduring renown, he asked those questions.