- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Writing to Geoffrey Dutton in 1969, Patrick White confesses: ‘All my life I have been rather bored, and I suppose in desperation I have been inclined to weave these fantasies in which I become more “involved”. Ignoble, au fond, but there have been a few results.’

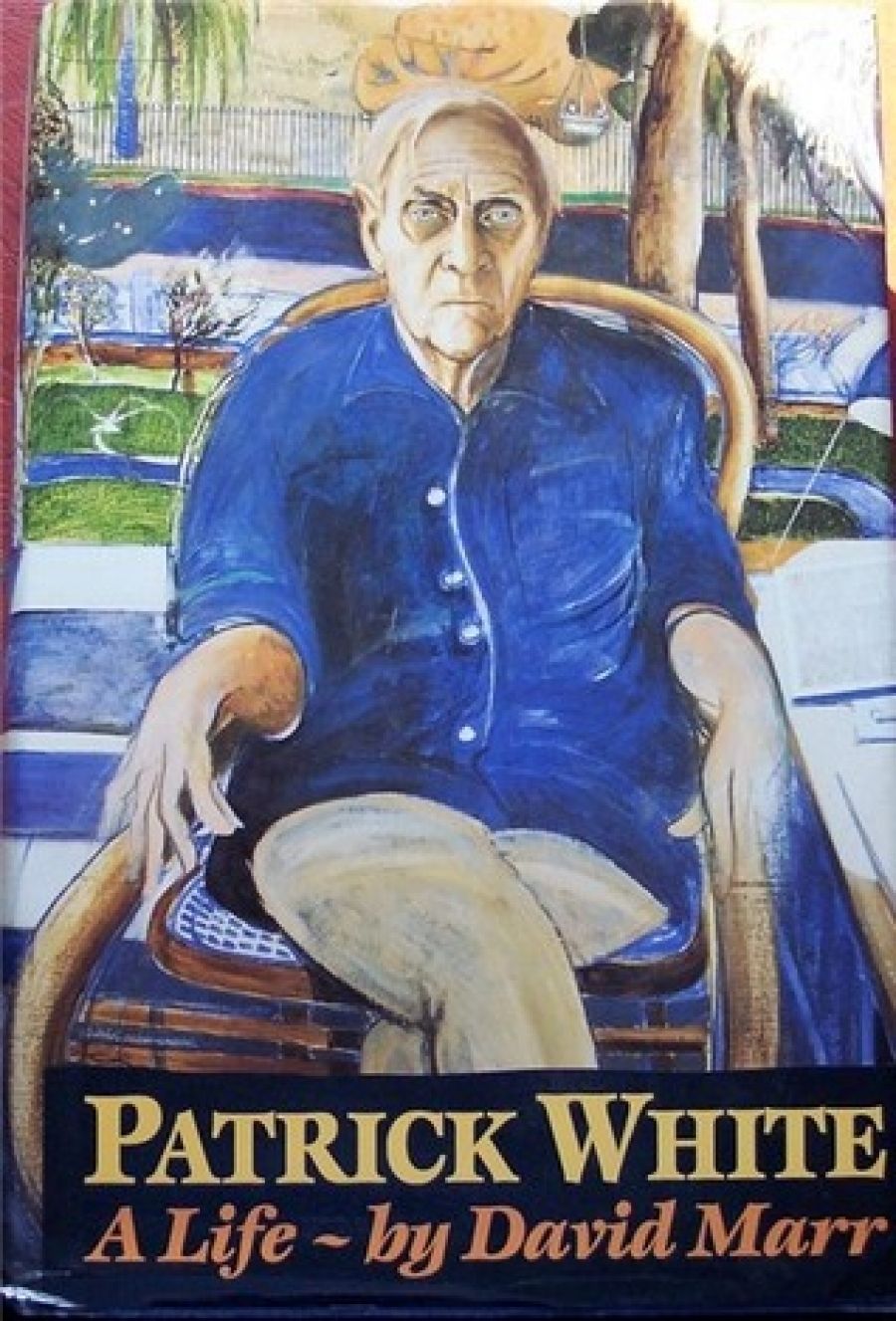

- Book 1 Title: Patrick White

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $49.95 hb, 727 pp

Writing to Geoffrey Dutton in 1969, Patrick White confesses: ‘All my life I have been rather bored, and I suppose in desperation I have been inclined to weave these fantasies in which I become more “involved”. Ignoble, au fond, but there have been a few results.’

He is speaking, in that typically wry last phrase, of the books. My guess is that one of the great frustrations of the last six years of his life was that for the first time in three decades he had no great book of his own to look forward to. A Life was meant to fill the gap. What he wanted it to be was not an apologia, or a cover-up, but what his books had always been, a revelation – anything else was too boring to contemplate. Having used his life, its landscapes and houses, his parents, his friends, all the fractured bits of his own psyche, to make the fiction, he wanted to turn the material over now to someone else and see it through their eyes. It wasn’t simply the events of a seventy-five-year existence that he was trusting to his biographer but the life material that had already gone into one lot of books and was now to make another. He set David Marr on the track of the documents, gave him access to all the names he would need, including those of people who would have some harsh truths to tell, then withdrew and waited. It was, among other things, a kind of test.

That Marr, in his role of investigator, should have come up with so much that White had forgotten, or obscured, or believed was lost, is one vindication of the old man’s choice. The other is an integrity, a passion for the truth, that White must have known would stand up to any attempt he might make to exert his authority – reclaim authorship, that is – by intimidation or bullying. The tact with which Marr keeps White at a distance while entering fully into the spirit of the man, the skill with which he covers so much time and space to compose a narrative that is shapely, detailed, and has pace, drama, and real complexity, is something of a miracle. White’s was a great life and David Marr has made a great book of it.

The difficulties, in fact, were huge. There was, for example, the special sympathy he had to discover for places that were, in their way, White’s sacred sites: the landscape round Belltrees that appears in so many forms in the fiction (as Rhine Towers, as Kudjeri), the southern highlands round Moss Vale, the streets around the river at Chelsea, later the Castle Hill of Sarsaparilla and, later again, Centennial Park. He had also to get to know the various houses, and to make himself, and us, at home with the Byzantine intricacies of the White/Withycombe inheritance, the town and country rituals of a privileged class that knew what it was to work and get its hands dirty, as well as to travel, collect, and play at ‘culture’ – he had to recreate, that is, a life of a quite peculiarly Australian kind that has largely vanished.

Later, there was the real Byzantine world that came to White through Manoly Lascaris and gave him access, beyond the sufferings and triumphs of Australian experience, to the darker history of contemporary Europe; then the war in the desert – Alexandria, the Sudan, Palestine; with always, behind and beneath, the Proustian litany of White’s illnesses, the asthma bouts and other crises. And all this had to be shown to have one life in real events and another in the books.

Marr is especially adroit at making the transition, through details and characters whose only relevance to his own narrative is the part they play in another. ‘At the front,’ he writes of Thirteen Eccleston Street, ‘was an antique shop run by a crazed and boring White Russian who was once an admiral in the Czarist navy. He was now, unknown to himself, waiting for his greatest engagement, as General Sokolnikov in the jardin exotique of the Hotel du Midi.’

What is chiefly impressive is the wholeness of White’s life as he himself experienced it, and the wholeness with which Marr recreates it. On almost the last page of his book, he writes of the room at Martin Road where White is dying: ‘On a calm morning he pointed out his favourite picture in the room: Max Watter’s grey painting of a country church: “It’s from the country round Belltrees.”’ White himself offers another insight into the way his affections continually led him back into the depths of his life. On a late trip to New Zealand to support a nuclear ban, he recalls after more than seventy years the South Sea Island gardener at Lulworth who came each day to collect him from kindergarten: ‘my small white hand in his large black spongy one as he helped me board the tram’. When his old nurse, Lizzie Kirk, died, aged ninety-six, he was asked if there was anything of Lizzie’s that he wanted. ‘He named,’ Marr writes, ‘the little worm-eaten trunk Lizzie had brought with her from Scotland. For years he had wanted it, but did not know how to ask.’ (It is typical that when Sid Kirk turned up with it, some weeks later, White should complain at the door: ‘You could have given me a ring.’) Affections of this sort, for houses and landscapes, for people, for many generations of dogs and all kinds of objects, was what held his life together.

He was fiercely loyal to those, such as Roy de Maistre and his American publisher, Ben Huebsch, who had helped discipline his art, but was most loyal of all to his own feelings. Marr makes a point about his difficult relationship with Australia that explains both White’s passionate attachment to the idea of the place, to his own edenic landscapes, and his bitter disappointment at the daily reality. The time is the 1950s:

Some part of him painfully grasped that he was not in the Australia of his childhood, the country which remained so vividly in his mind as a paradise of order and comfort, of freedom, primitive sensuality, well-run houses and beautiful gardens. Had he grown up in Australia, these early memories might have been overlaid by a truer picture of the country. Exile, instead, had preserved the country in all the colours of early memory. All his life Patrick White was to draw on those memories while raging at the reality around him.

His worst anger was always reserved for what he had loved and what had, he felt, let him down – and especially for those artists among his friends who, in his eyes, had compromised the great hopes he had for them by chasing after money or public affection or fame.

Marr writes of his affection, late in his life, for Kerry Walker: ‘a daughter to worry over, help out, quarrel with and take pride in as her career grew. She broke many of his rules but was admired.’ There were other daughters – Zoe Caldwell, whom he misses at the end, Luciana Arrighi, Kate Fitzpatrick – and a good many sons as well. Not all of them broke the rules and got away with it, and many were kept on the straight and narrow by the knowledge of his eagle eye upon them. Harshness, in his case, is always an indication of dangerous involvement. This is also true of his harshness towards himself. He was afraid all his life of going soft, of being sentimental, because the possibility of it was so strong in him. (It was de Maistre who put the iron in his soul in this regard – to the great benefit of the work.) He had always to be wary of the ‘easily seductive’ (he was especially hard on male beauty) because he was so susceptible, and of the dangers of courting public approval because he was by nature vain.

‘God and love are the two great mysteries of White’s world’, Marr tells us when he approaches this difficult territory of the affections:

The place of love in his novels is peculiar, for White is not much interested in falling in love, which is the central drama of most Western fiction. Few lives are shaped by the search for pleasure in Patrick White; his men and women sacrifice very little for passion; and more often than not the people who matter most are haunted by their inability to love enough ... Sex is necessary in White’s world. Sex offers relief from lust. It is a service offered and taken. The many whores of White’s fiction are saints who pursue in bed and on street corners their vocation: they are the nuns of relief ... The great hazard is self-disgust ... Love makes sex bearable. ‘Personally I find sex without love so boring.’ And what was this love? Nothing White experienced as a man displaced Lizzie Clark’s example from his heart. Her love was the selfless devotion of a servant for her charge ... Love is Service ...

This is an important passage that goes a long way towards explaining the complexities of the man and the moral and spiritual hierarchies, the judgements and dismissals, of the fiction. That it is fairly conventional in no way diminishes the power with which he uses it.

The real monsters of his world are those, such as Waldo Brown, who are incapable of love; they are worse than any of the physical tormentors. Waldo represents what he himself might have become, without a certain grace, some luck, a good deal of discipline and the daring to break free of his own ‘nature’. He was aware always of that mixture of lust and self-disgust, of pride and contempt for others, that marks the Waldos of this world – most of all, the sterility that comes from cutting off the sources of feeling. His heroines are those who triumph over their own pride and isolation, his saints those who offer loving service, especially those who tend the sick. Everything that has to do with the humble domestic world of washing and cleaning and the preparation of food is sacred to him.

Writing to his Spanish lover, Mamblas, soon after he set up in Eccleston Street in 1938, White muses: ‘There always seems to be plenty of domestic detail to attend to ... I suppose really I have the soul of a Hausfrau.’ That was one of its incarnations. Writing sharply to his old enemy, Time, which had spoken of his living with a ‘male housekeeper’, he insisted, ‘I am the housekeeper’. Riding down to Kent with the sister of his agent, who feared ‘a heavy literary discussion, White raised the question of Hoovering rooms: how often did it have to be done? His own position was, once a week, but thoroughly.’

Hausfrau, but also – especially in his Ebury and Eccleston Street days – dandy; later, as Marr lists it, ‘patron, benefactor, gardener, gossip and authority on questions of marriage, children, education, manners and good form’. Also, one might add, monk. There was something very austere and cell-like about the upstairs rooms at Martin Road, and increasingly, in later years, about the man. The search, like Eudoxia/Eddie/Mrs Trist’s, was for purity. ‘Since there was an income of any size,’ he writes to Dutton in a late letter, ‘I have been giving it away. By now I give most of it – not a noble gesture when one no longer has much desire for anything beyond a roof, a bed, a table and a few pots and pans.’ He was hugely generous and quiet about it. He could also be a skinflint, especially about postage, and tormented his publishers to the end with single-spaced manuscripts of the novels, offering only the most disingenuous explanations of excuse: ‘My hand must have slipped and the spacing gadget shot up to single spacing. I did not notice until I had typed about twenty-five pages. As it did not seem to me to look too bad, and because it would cost less to send, I continued typing that way.’ This in 1975, two years after the Prize!

The tightness was a family trait. So was the generosity, part of what Marr points to as a strong sense of ‘civic duty’, though it also sprang from a natural charity. He was himself, in his later years, a great visitor of the sick.

Marriage? From the beginning what he was set on was a permanent relationship. After a few false moves, which we read about in detail here for the first time, he found his life partner, and for the next forty-six years, despite the usual difficulties and the unusual ones posed by his own abrasive and sometimes cruel nature, they stuck to it. He was fiercely intolerant of those who gave up. ‘The passion,’ Marr writes, ‘seemed to grow from his fears, for if men and women with children should break up, how much more vulnerable must the union of homosexuals be.’ White left many moving testimonials to the splendours and miseries of a lifelong marriage, in Signal Driver, in the ‘Journeys’ section of Flaws in the Glass. His life as he saw it, his work too, would have been impossible without Manoly.

As for ‘homosexuality’, Marr treats that with the coolness one might expect of a man who refers to it as ‘a commonplace of human nature’. There is no psychology, no special pleading, no prurience, no gossip, no camp.

The most painful part of the book has to do with the way White, at various times in his life, got rid of those who no longer interested him; had nothing more to offer in the way of insights for what he was writing, no new ideas or pleasures. It was that tendency to boredom again, a restlessness in him that kept him boiling but was necessary as well for the renewal of his work. Once he had decided to get rid of someone he was brutal. ‘You’ll get it in the neck yet,’ Lascaris warns Gretel Feher.

The most general of these bloodlettings involved the Central Europeans, Jews mostly, who had been the support of his early years at Dogwoods, sharing his sense of isolation, introducing him to music, providing some of the impetus for Riders in the Chariot. His break with them coincided with the move to Martin Road, when he had also to slaughter the last of their chooks. ‘I must commit murder twice a week before we go,’ he writes to Dutton’, and they come racing towards me, wings outstretched, asking for it.’

There are many things here that surprise and illuminate. How close White came, just before the war, for example, to choosing America rather than ‘home’; that he went to Cornwall, and later all the way to New Mexico, on the track of Lawrence; what it was exactly that the experience of the war gave him (‘The rich,’ Marr writes, ‘are able to choose the company they keep, but White had spent the war years thrown in with the crowd and discovered to his surprise that he could deal with mankind at random. The fear of being cut off from the human race no longer afflicted him ...’); that when he first came back to Australia after the war it was in a hundred-man dormitory along with other migrants; that he had no response at the time to the political events of Europe in the thirties, to Nazism, to the fate of the Jews; that he voted Liberal until 1969, was drawn into public life by the Vietnam War, and became an activist by risking jail in Chifley Square on 9 December 1969; that he sat down and talked with an Aboriginal Australian for the first time in 1965.

Marr gives an excellent account of White’s relationship with de Maistre, to whom he owed, at least in part, the extraordinary development of his ideas between The Ploughman (which seems barely aware even of Eliot) and the fully fledged modernism of Happy Valley. He also reveals the process by which Nobel laureates are made. There are tantalising snippets from many letters, including the ones White wrote in the 1980s to world leaders: to Reagan, ‘Come on, cowboy!’; to Thatcher, ‘I urge you to search your heart, Mrs Thatcher, if one exists behind the pearls.’ (They were sent for publication to the New York Times, The Times and Le Monde. As Marr puts it, ‘None appeared’.) Marr has a nice line in irony. ‘To mark each medal,’ he writes of the Nobel Ceremony, ‘the Stockholm Philharmonic in the gallery above the stage played an interlude of appropriate music. To honour Patrick White for introducing “a new continent to literature” the band played Percy Grainger’s “In an English Country Garden”.’

When White was reading a new book he looked first at the opening paragraph then at the last, and hoped, somewhere between the two, for a good cry. A Life cannot have disappointed him, though he did not, of course, in the draft he read just before his death, see the end as it now stands – Marr’s description of the scattering of his ashes in Centennial Park:

White had chosen a scruffy stretch of water where he used to rest on a bench in a clump of melaleucas. Could it not be one of the beautiful lakes, Lascaris had asked? It had to be this: heavy with lilies, with a scurf of plastic and broken glass along the bank. The sun was not yet up and a mist was on the water. Barbara Mobbs kicked aside a few empty cans and prayed. As Manoly poured out the ashes a pair of ducks swam over to investigate, hoping for bread.

Every detail of that leads us back into the pattern of the book and into the life.