- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The editors of Who Do You Think You Are? cheerfully point out the imprecision and contradictoriness of the second part of their title. ‘How can you be born in Australia and also be an immigrant? If you were not born in Australia but came here at an early age, how can you be second generation?’ Nevertheless, they have chosen to regard the linguistic slipperiness and confusion inherent in the term ‘second generation immigrant’ as being appropriate to the social reality of those to whom it refers. The thirty-five contributors are therefore predominantly women who were born in Australia of immigrant parents or who came to Australia at an early age.

- Book 1 Title: Who Do You Think You Are?

- Book 1 Subtitle: Second generation immigrant women in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Women’s Redress Press, $14.95 pb

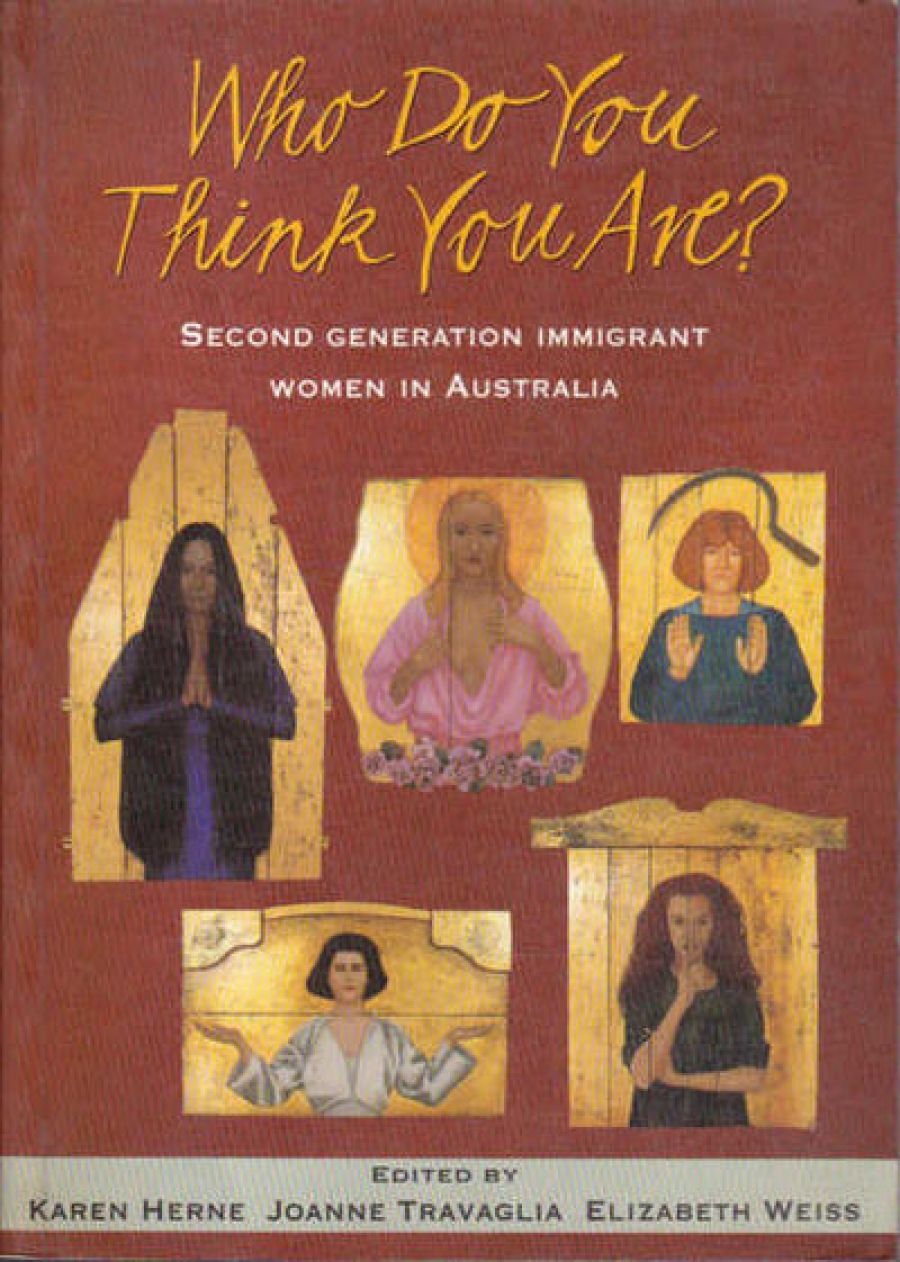

For the record, my immigrant forbears were maternal great-great-grandparents and paternal great-grandparents, all WASP. It may as well be confessed that when I was handed this book, with its maroon cover highlighting pictures of contemporary women drawn as religious icons, I expected a reading experience that would be somewhat lumpish and unpalatable, but good for me. Fortunately, in terms of the pleasure of the experience, this expectation proved misguided.

The contributors come from sixteen different ethnic backgrounds. The collection includes poems, stories, illustrations, and autobiographical fragments. The longest piece is Maria Pallotta-Chiarolll’s sociological article, entitled ‘What About Me?: A study of Italian-Australian lesbians’. Most of the contributions are four pages or less. Rita La Bianca’s ‘Dinkum Italian’ is a moving collage of utterances snatched from immediately identifiable though undepicted contexts, newspaper clippings and the pronouncements of politicians. The real achievement of this book is that, despite the diversity and brevity of the various pieces, it has avoided becoming a compilation of slivers, or a cacophony. Rather, Who Do You Think You Are? is an engaging blend of voices and images, expressing both common truths and different perspectives. A wide range of emotions is evoked and articulated, from humour to pathos to the unmitigated anger of Nadya Stani’s non-fictional piece, ‘Going Home’.

What is entertaining is the freedom of these ‘second generation immigrants’ to say things about themselves and their backgrounds that ‘we’ are tacitly prohibited from saying. An example is Joanne Travaglia’s and Elizabeth Weiss’s mocking tribute to bonbonniere. Another is the liberty that some of the contributors have taken in the Biographical Notes: ‘Linda Leung was born a Gemini in the Year of the Pig, making her a greedy, two-faced sow.’

The book is also well organised, with some lovely transitions. Enza Gandolfo’s story, ‘Claudia’s Grandmother’ depicts the over-dependent relationship of an Italian grandmother and her favourite grandchild. Gandolfo’s happy ending is followed by Marisa Fazio’s ‘Nonna Makes Me Coffee’, where an Italian grandmother and her grand-daughter are parodied with inspired bogusness:

‘See that photo of you in a bikini when you were young? ls that nonno (grandfather) applying suntan lotion to you stomach?’ I am pointing to a photo on the mantelpiece which is directly behind her. Nonna turns to look. It gives me enough time to switch her cup of coffee for mine. ‘No, no, that’s the parish priest. We won’t go into that, no, no, no!’

As a child of refugees, I want a world where we learn tolerance as a primary characteristic, with responsibility and respect rather than competing rights, where we are not looking to the tribe for identity and creating outsiders to make us feel good.

Giulia Giuffre ends her autobiographical piece, from which the book takes its title, on a positive note ‘The doubleness, indeed, the multiplicity of personal, national and cultural reference, sometimes a burden, is much more often a gift.’ On the whole, Who Do You Think You Are? has succeeded in putting into practice Maria Pallotta-Chiarolli’s assertion that ‘Women should be able to speak of the positive appreciation and upholding of their multiple subjectivities and cultures’.

Comments powered by CComment