- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: War

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

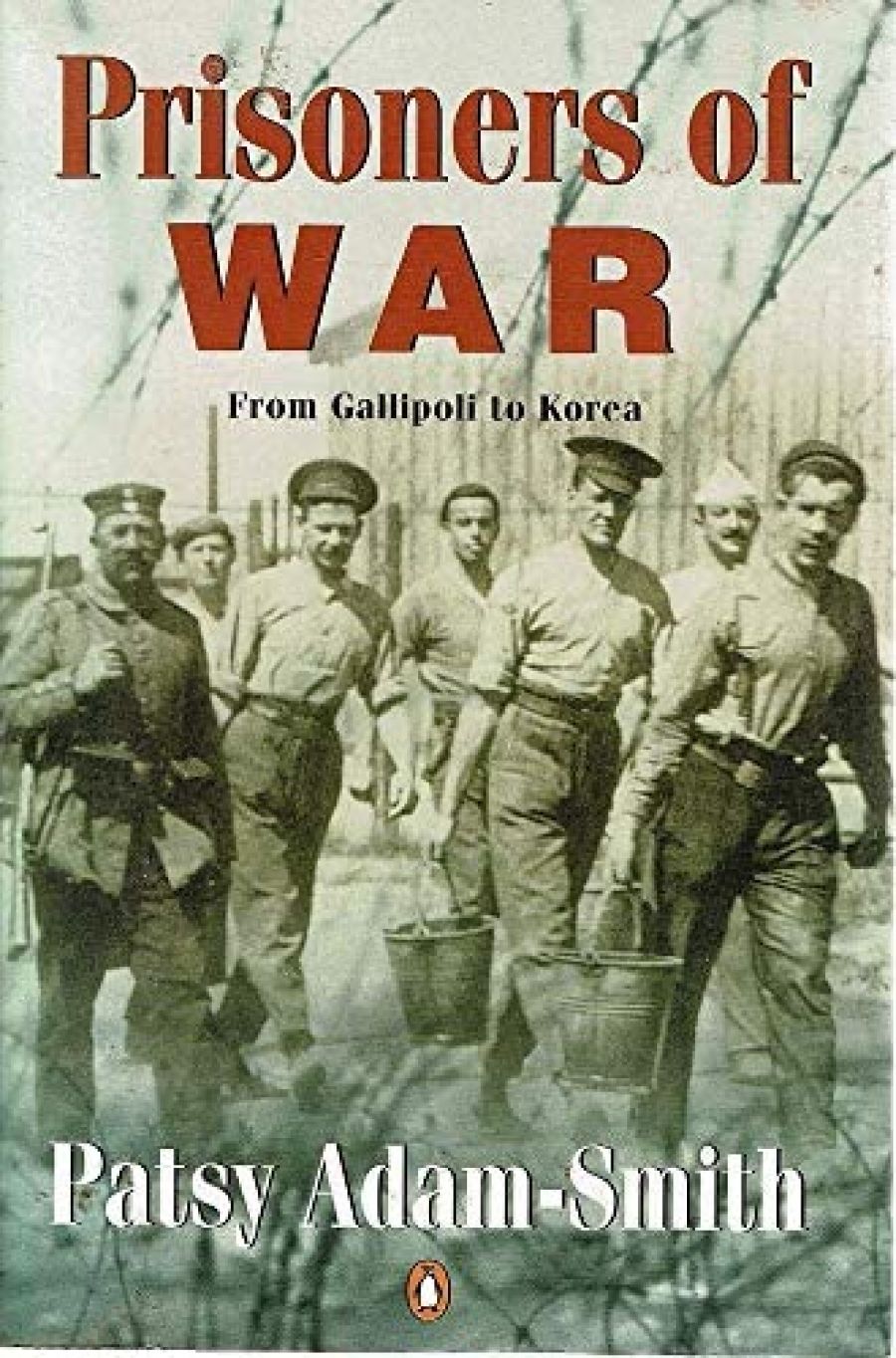

The word history means many different things to different people. But generally speaking it entails an attempt by an author to explain, or make sense of, the past. That is, the historian gathers together the material, the evidence as it were, and from that draws a number of conclusions which we as readers are expected to believe. Prisoners of War, by Patsy Adam-Smith, encompassing three wars, from Gallipoli to Korea, is not that kind of history.

- Book 1 Title: Prisoners of War

- Book 1 Subtitle: From Gallipoli to Korea

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $45 hb, 599 pp

Rather it brings to life a multitude of voices from the past and gives them a voice with which to tell their story. The past is not explained away as histories tend to do. Instead it is shown to be still very much of the present.

Some 922,000 men and women enlisted during World War II at a time when the population was only slightly more than seven million. Practically every able body was doing their bit. If this book makes one statement it is that, at times of crisis, people pull together, both on the home front and at ‘the front’. Concomitantly, there is a strong sense that ‘higher-ups’ can’t be trusted to get things right, that somehow the men were betrayed by incompetence at the top, which is surely an Australian cliché.

The method of writing owes much to Bean, Australia’s official historian for World War I, in that it concentrates on individuals. You get the big picture through the eyes of the people who were there. Adam-Smith adroitly weaves a number of stories together, thereby broadening considerably the perspective. The view is always panoramic. The years of research spent putting this book together are evident on every page. She interviewed dozens of former prisoners of war and their spouses, and accompanied a number of interviewees overseas to visit old battlegrounds and prison camps. These places are eerie, and no matter how many years have passed, they always feel haunted.

The travelling must have been an endurance test. The list makes an impressive itinerary: Yugoslavia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Russia, Austria, France, Italy, Switzerland, Turkey, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Syria, Jordan, Iraq. She also accompanied ex-prisoners of the Japanese to Thailand, Burma, Malaysia, Singapore, Borneo, Java, Sumatra, New Britain, and New Guinea. A visit to Singapore is not complete without a trip to Changi: some of the railroad that cost hundreds of Australians their lives to build still exists. But the list also contains a great number of places where you would not normally have thought Australians to be.

Remarkably, very few of the participants in this tale are bitter. Signalman Peter Oates said of himself, more than forty years after the events: ‘The only difference between what I was doing and what a juvenile delinquent does these days is that the King gave you medals for it.’

Within these pages are stories that horrify, right alongside humorous stories of exploits that seem to belong to an Indiana Jones film. As RAF Navigator Geoff Breaden put it, ‘much of the truth was too preposterous’. The scope of this work is immense, and it is a powerful reminder of the unloveliness of wars, and it reminds us, too, that we mustn’t forget those who fought them for us. The great pity is that the author tells us this will be her last work of non-fiction. I hope someone changes her mind.

Comments powered by CComment