- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Janine Haines’s book, Suffrage to Sufferance is a good read. For women who are in public life and who insist on equality, it is a realistic and often humorous read. For those women who aspire to public life or simply equal rights, it is an entertaining – lost journalistic – account of where women’s aspirations might lead them. For men who understand or want to understand women’s drive for equality, there is an idea of the barriers, seen and unseen, that women face. And there is some sense of women’s struggle for political influence and recognition.

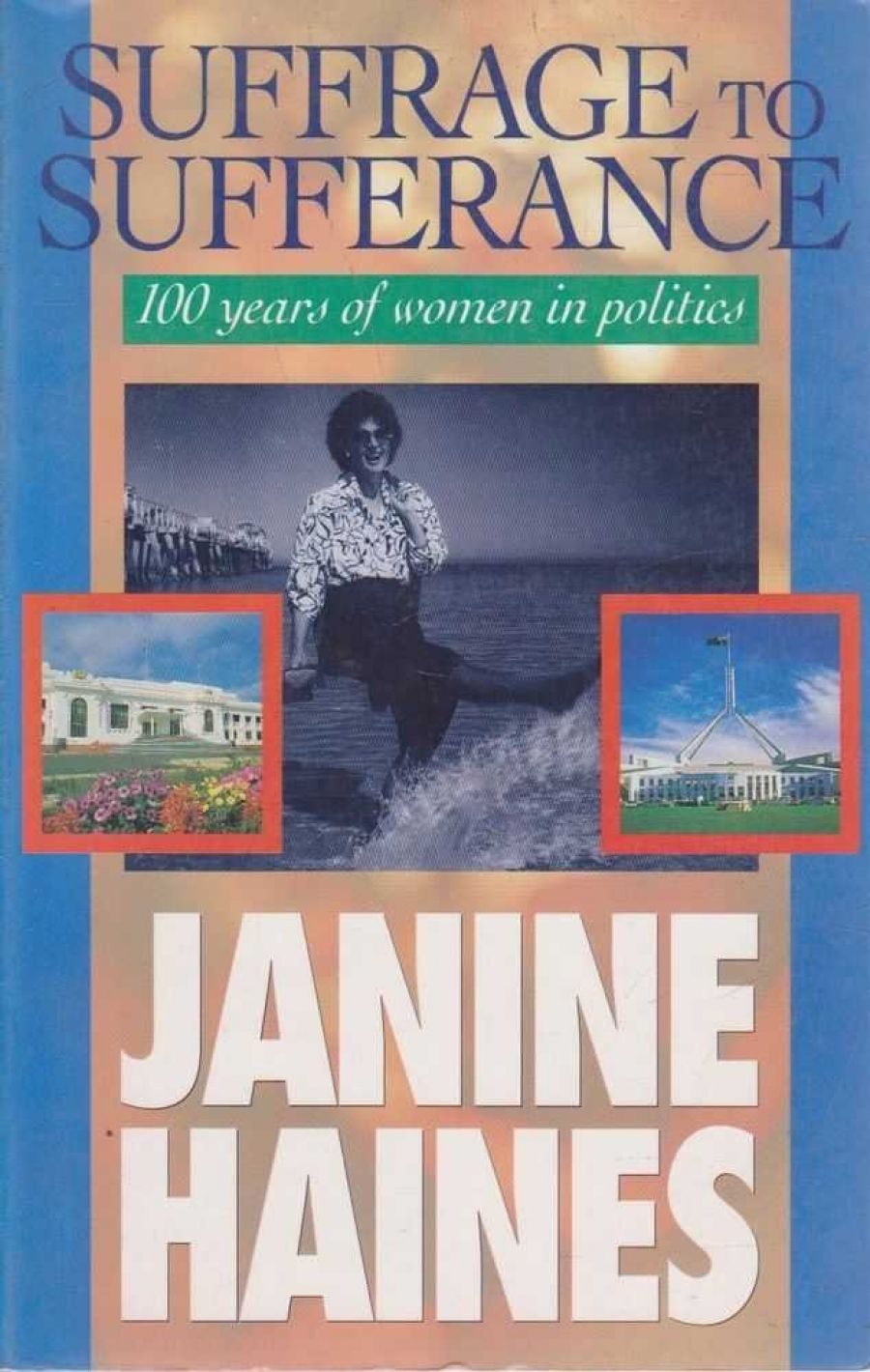

- Book 1 Title: Suffrage to Sufferance

- Book 1 Subtitle: 100 years of women in politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $14.95 pb

The author captured my attention in the first line of the introduction. Like so many women MPs, staffers and workers, as she walked into the Senate chamber on her first day in Parliament, she realised that the preponderance of men meant that ‘their priorities dominated the debate and the legislative programs’.

The book then describes briefly the impact of years of male domination on women’s political careers, aspirations, and achievements. To that description the author brings an acerbic wit. Many of Janine Haines’s experiences mirror and highlight the collective experiences of women in public life – especially if we subscribe to that eight-letter word, feminist.

British Conservative MP Teresa Gorman recites how disconcerted she was by the following incident which most women members of Parliament have experienced:

a group of four of us new Tory women MPs sat together in the dining room. It caused an uproar. The turkey cocks surrounded us. They just couldn’t let women sit unaccompanied, and eventually they squeezed in between us to disrupt our female chat. In the chamber, too, their behaviour can be disgraceful. When one of the other side gets up, particularly on a woman’s issue, they shout things like: ‘Is that a man or a woman – you can’t tell the difference.’

The book clearly reveals Ms Haines’s anger and frustration with the constant questioning of her role as mother, wife, and politician (in that order). It is a questioning that most males in public life are spared: ‘Certainly many people were disappointed that Ian and I stayed married and that the children were never made wards of the state.’

The book honours the pioneers of the women’s movement. The women who were prepared to face the pain and indignity of force-feeding to win public support for our right to vote and our right to sound and economic independence.

And Janine Haines identifies correctly one of the powerful motivating forces behind women’s courage and commitment in the political struggle to the fact that ‘women were fighting for their children’s welfare, as much as for their own’. This force broke down class barriers until British women were given the vote in 1918 as a reward for their action during World War I.

For women, moving from the polling booth to the parliament was just as difficult a struggle. The next move – to half of the Parliaments and to prime minister and chief justice – is yet to be achieved in Australia.

Why is it such a struggle for women? The answers are more suggestions than in-depth analysis. Ms Haines suggests that one reason is the lack of teaching about women’s activist roles in Australia’s history. Whatever the reasons, put briefly as Janine Haines’s book does, it is incredible that the human rights of one half of the population were resisted for so long – and in Australia are still not rights but barely tolerated privileges.

It is refreshing to read Susan Ryan, Catherine Spence, Selina Anderson, Nellie Martel, and Mary Ann Moore-Bentley being described, among other important women, as illustrious pioneers of women’s rights to fully participate in shaping society to meet women’s needs. The struggle for equal pay was just as arduous – it took sixty-five years to achieve after the original basic wage action.

Janine Haines’s writing and her career, like that of Dame Enid Lyons, continually affirms the experience of women as different but as important for democracy and in some ways more appraising of the needs of all people in the community than the experiences of businessmen or lawyers.

The campaign for women’s rights led by one of our outstanding pioneers Jessie Street, encapsulated the difficulty of women to beat or break through the traditional political power structures. Janine Haines would argue that this is why the more referendum-based pre-selection and policy developments processes of the Democrats have attracted more women candidates. If that is true, it is ironic that the ultimate in political sexist attacks destroyed the leadership career of Janet Powell, Janine Haines’s successor.

And of the future? Janine Haines seems pessimistic:

The heady days of the 1970s and early 1980s in Australia which saw Equal Employment Opportunity Acts, equal pay and anti-discrimination legislation passed at state and federal levels, along with abortion-law reform, rape-law reform and the introduction of some low-key affirmative action programs, were historical highlights, but while they were exciting they were also short lived. This fact is equally frustrating. It is as if the men have decided that women have had their turn and it’s now back to (male) business as usual.

Her book ends with a stark prophecy on the potential impact which might be applied to the new Victorian Liberal Government’s policy on women:

Whether it is the man who notes snidely that women are a bargain for employers because while they are only 90 per cent as efficient as men, they are twenty per cent cheaper to employ, or the woman who asks when the Liberal Party is going to ‘stand up to the sisterhood’ and consider the needs of ‘real Australian women’ they send a clear signal that, nearly a century after suffrage women are barely tolerated in politics and are still not accepted as fully functioning beings in society.

We may not know Janine Haines much better personally through her book, but some will feel more committed to continuing the struggle for equal power and human rights for women.

Comments powered by CComment