- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Surprising revelations about Aboriginal art

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Morphy’s monograph is an instance of a problem in anthropological writing about Australian Aboriginal people, a problem of audiences. The public this book will reach (and please and enrich enormously) is international, made up of several thousand mostly Anglophone anthropologists students of art, particularly those researching or teaching about the contexts in which the art of non-Western peoples is created and first consumed. Yet the art of North East Arnhem Land (the Nhulunbuy/Yirrkala region) appeals to a much larger and more heterogeneous public than this. It is likely that Australians comprise a majority of this second public. Morphy, adviser to the Australian National Gallery in the later 1970s and early 1980s, can take some credit for that. And there is a third and even larger public still: those Australians who infrequently go to art galleries (they might spend a few hours in the ANG on a Canberra trip) but who are susceptible to a more informed perception of the subtlety, beauty and (most important) resilience of the classical heritage of Aboriginal culture.

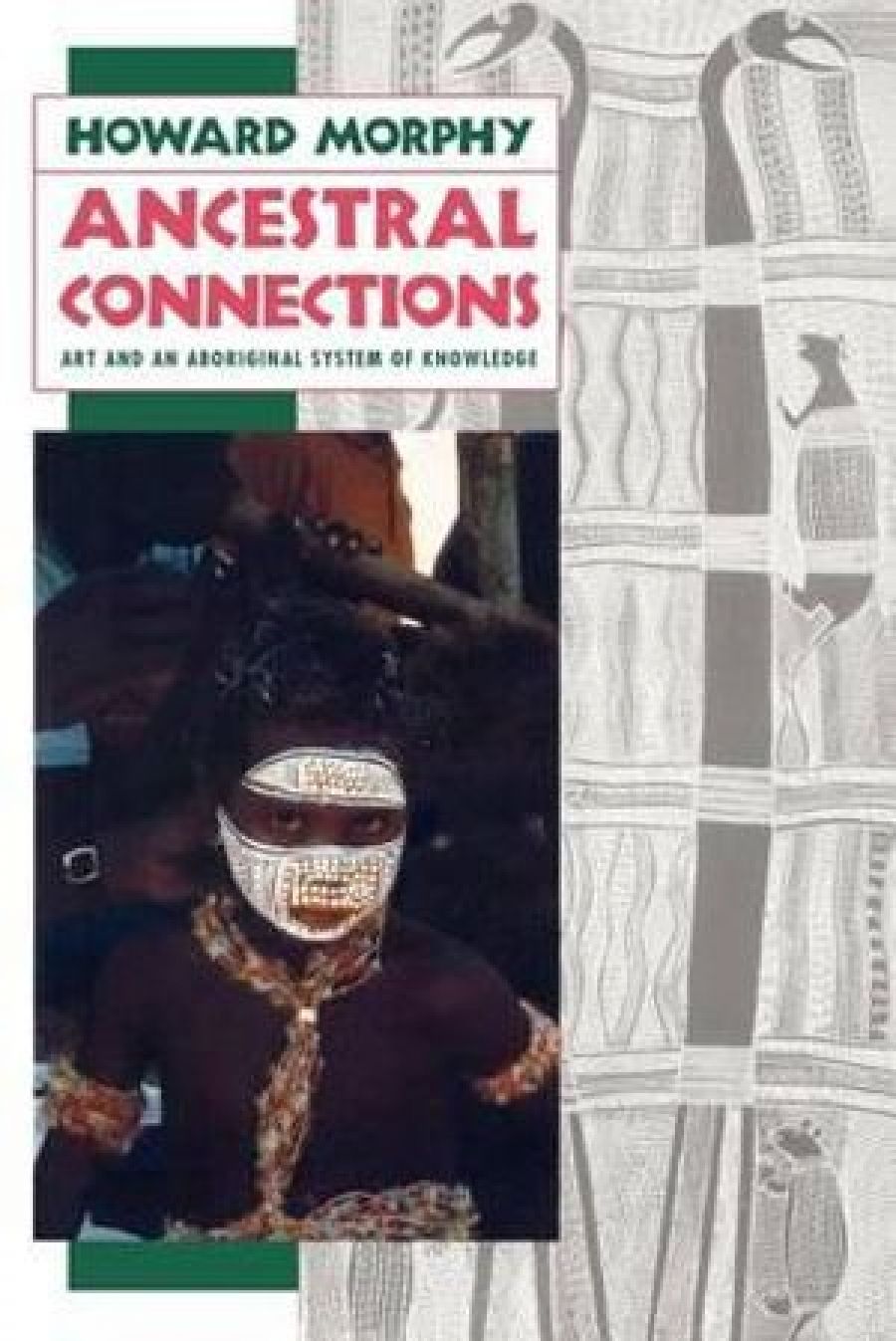

- Book 1 Title: Ancestral Connections

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art and an Aboriginal system of knowledge

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, $36.95 pb

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/ancestral-connections-howard-morphy/book/9780226538662.html

Bringing some of the themes of this book to the latter two audiences will be one of the more difficult challenges facing the educational practices we call ‘Aboriginal Studies’.

Perhaps Morphy’s most surprising claim about the art of Yolngu (people of Arnhem Land) is that the cross-hatching which fills the spaces between figures in Arnhem Land paintings is no mere decorative filler. Rather it is the densest and most important item in the painter’s visual vocabulary. As Morphy explains, the diamonds formed by cross-hatching are the symbols of clans: each clan has diamonds slightly different in shape to those of other clans. These ‘diamonds’ are only in a superficial sense analogous to ‘logos’ or trade symbols, for they embody the ‘ancestral power’ which is the clan’s inheritance. Morphy emphasises the difference between a design merely representing and a design embodying that power.

Finally, these cross-hatchings are the most expressive and meaningful elements of the paintings in which they appear. The last third of Ancestral Connections, before Morphy’s conclusion, is a demonstration of this point about meaning. By closely reading a series of paintings belonging to one Yirrkala clan, the Manggalili, Morphy turns the non-Aboriginal reputation of Yolngu art on its head. It is common for us to marvel at the way artists such as the late Narritjin Maymuru (Morphy’s Manggalili friend and teacher) have rendered recognisable animals and objects; but for those authorised to paint and to explicate these representational figures are only literal elucidations of one of many possible meanings that are buried within the cross-hatchings which surround such figures. Morphy persuades us that Yirrkala art is fundamentally an art of abstraction, and only secondarily an art of representation.

The social logic of this symbolic order is Morphy’s principal theme. He tells us that he changed his basic question from ‘What does it mean?’ to ‘How does it mean?’.

Yolngu society is structured around a distinction (a continuum, rather than a hard and fast boundary) between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ knowledge. To grow up, to acquire maturity and power, is to be given access to more and more inside knowledge, to glimpse more and more of the power of the sacred that lies beyond the mundane. The abstraction of Yolngu art is essential to the political management of such access, that is, to the definition and elaboration of a realm of inside knowledge. Painters and those authorised to give accounts of what is in a painting can make a cross-hatched surface mean so much. To marvel at a beautifully drafted animal is thus to view these barks as a Yolngu child would (except that unlike the Yolngu child we might not even know, without Morphy’s help, that there was much, much more to be disclosed).

‘Secrecy’, in Morphy’s discussion turns out to be a subtle and historically malleable practice: ‘There is no set and agreed body of public or secret knowledge.’ That is, the inside- outside continuum is managed strategically. There seem to be at least two senses in which this is so.

First, Morphy argues that Yolngu secrecy is best understood as a theatrics of disclosure: ‘Although secrecy is important in the creation of men’s power, it is equally important that women and uninitiated men know something of what men are controlling. This is what creates the power of secrecy.’ Such glimpses of ‘inside’ meaning and power both awe and bind those who see.

Second, the ways in which paintings embody powerful secrets has changed, now that likanbuy paintings have circulated as Art for the nonYolngu public. Let me gloss Morphy glossing likanbuy: it means ‘connective’ (with ancestors, powers, places). According to Donald Thomson, who investigated Yolngu art forty years before Morphy, the designs which distinguish likanbuy art were once restricted from circulation. Now that much likanbuy art is to be seen in books and on gallery walls, there remain restrictions of other kinds or levels: who can produce likanbuy, who possesses knowledge of their inner meanings and who can articulate such knowledge.

In arguing that this change demonstrates the adaptive potential of the Yolngu knowledge system, Morphy has answered some of the more romantically pessimistic projections of Aboriginal futures – that ‘commodification’ of art is a disease fatal to ‘culture’. A more informed view can trace the reconstituted dynamics of secrecy. Women, though still basically enthralled by senior men’s control over inside/outside, have more inside knowledge and more responsibility in producing paintings than they used to. In a footnote, Morphy tells us that older men account for their greater willingness to share secrets with women by pointing to the increased unreliability of young men, as boozing (and drinking kava, I wonder?) becomes a more common pastime. Everything in this book tells us that a political logic underlies releases of Yolngu knowledge; so why share any of it with Morphy? Narritjin Maymuru, in particular, emerges as tough, generous but bluntly strategic, sometimes charging the anthropologist money for taking up valuable painting time with questions. Are the riches of this monograph Narritjin’s gift to a visitor whose persistence made him a friend? If so, then the reader’s respect and reciprocity is being solicited as well. Morphy’s introductory remarks on the history of Yirrkala Mission tell us that powerful Yolngu have sometimes afforded key balanda (non-Aboriginal people) glimpses of the energies animating those crosshatchings. To be so included is to take up some responsibility for the social reproduction of Yolngu ways, or so the Yolngu hope. Morphy’s book embodies the political logic of such revelatory action; it does not merely represent that logic from an external position.

That’s why the things Morphy can say should be going to a public much wider than the specialists.

Comments powered by CComment