- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sandra Holmes’s Yirawala: Painter of the Dreaming is not a picture book or a ‘pretty story’. It does not tell balanda (white people) what they want to hear, nor does it euphemise the truth. The book is an inspiring, if harrowing account of Yirawala’s life and death, his religion manifest as art, and his struggle with balanda officialdom to regain title to his Dreaming country, Marugulidban.

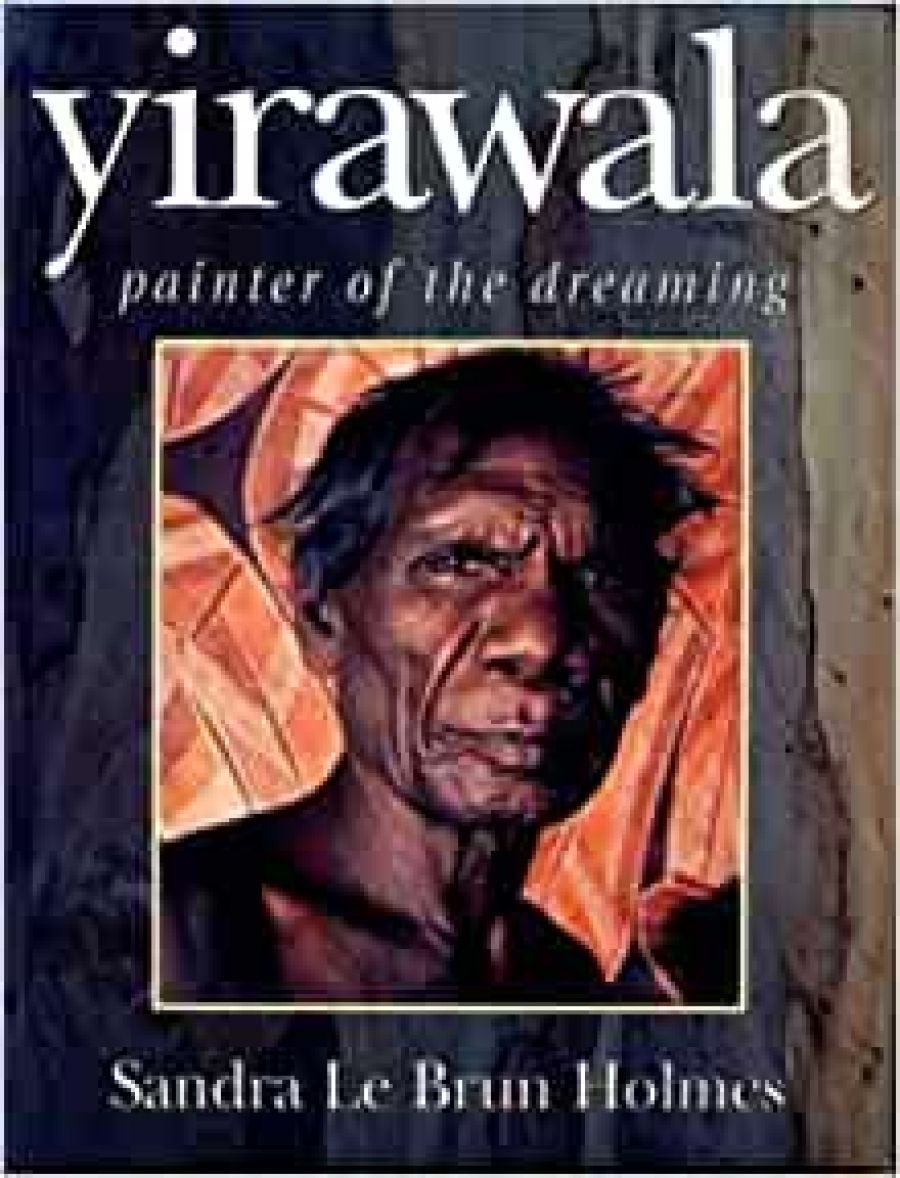

- Book 1 Title: Yirawala

- Book 1 Subtitle: Painter of the dreaming

- Book 1 Biblio: Hodder & Stoughton, $59.95

Before narrating the last twelve years of Yirawala’s life (1964–76) – the heart of the book – Holmes exposes the ‘bloody’ history of balanda invasion. The theft of Aboriginal land, massacre of entire clans, kidnapping of children, enslavement of Aboriginal people on pastoral stations, and ethnocide on missions are strongly stated as background to Holmes’s discussion of Yirawala, a man of great authority and wisdom. Holmes records loss of languages, profaning of sacred sites, mockery of Aboriginal religion, and the denial of basic human rights which occurred and is still occurring as a result of colonisation. As Holmes points out in her text, mission authorities and government officials conspired to disempower and hold control of Aboriginal people who were locked out of their country and forced to accept the ‘hand out mentality’ of a ‘sit down’ existence contrary to their dignity and pride as human beings.

Holmes, however, is not content with generalisations. The material for her book is taken from tape recordings, letters, documents, and diaries. Her attention is sharply focused on Yirawala and on the years 1964–76 when she was intent on building a collection of Yirawala’s ceremonial works. Allied to this intention was her impetus to record the meanings (inside and public) of all the paintings and to preserve the collection intact, as a permanent record of Gunwinggu religion as presently by one man. The events and experiences of these years, traumatic as well as moving, accurately document the political and social inequalities endured by Aboriginal people at the time.

Although Yirawala was admired by Picasso and was lauded in ethnocentric terms as the ‘Picasso of Arnhem Land’, art is not the dominant focus of this book, but rather, Yirawala’s devastating battle with balanda officialdom on many levels. His burning mission to re-establish Marugulidban as a permanent future home, not just as a ‘painting centre’ or outstation, is defeated by the politics of the time. The dream of returning to live from the land, independent of balanda demands and control, unthreatened by mining, alcohol, a money economy, the ‘arts and crafts industry’, is impossible because colonisation cannot be excised. The invasion cannot be unwritten. (An irony unstated in the book is that the Northern Territory Land Rights Act was passed in 1976, the year of Yirawala’s death.)

The author’s aim to present Yirawala’s story through his own eyes, is achieved as well as any non-Aboriginal biographer can hope for, writing in English, limited to what the informant has revealed or stated. The book is, however, also a first-person account of Holmes’s own battles with mission and government authorities to purchase all of Yirawala’s paintings and establish a Yirawala museum. These aims are constantly thwarted by lack of funds, and the fact that Holmes lived in Darwin while Yirawala resided on Croker Island. The author’s personal aims, as revealed in the narrative, are inseparable from Yirawala’s intense desire for social justice, political recognition, land rights, and maintenance of his religion.

The climax of the book is the series of 139 colour plates which are revealed as ‘leaves of the sacred book’ of Yirawala’s religion. The designs that only Yirawala could paint, inherited from his father and father’s father, are an undiluted expression of the power of his religion and the depth of his knowledge. In accordance with the artist’s wishes, the explanation of the Maraian Series (plates 1-82) details only the public layer of meaning. Yirawala’s paintings are inseparable from religion, politics, law ceremony, land ownership, and life itself, as this book profoundly demonstrates.

Yirawala: Painter of the Dreaming has a much tougher approach than Sandra Holmes’s earlier publication, Yirawala: Artist and Man, (Jacaranda Press, 1972). The current text is strongly political, being fiercely critical of government assimilationist policy. The Aboriginal ‘arts and crafts industry’ is criticised for forcing a separation between art and religion which runs counter to the principles of Aboriginal culture.

Yirawala, the hero of the narrative, was strong in his refusal to surrender to balanda demands to mine his territory in exchange for money. His paintings have deep ceremonial significance and can be read as ‘title deeds’ to his land which could never be equated in terms of money: white man’s Dreaming.

Comments powered by CComment