- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

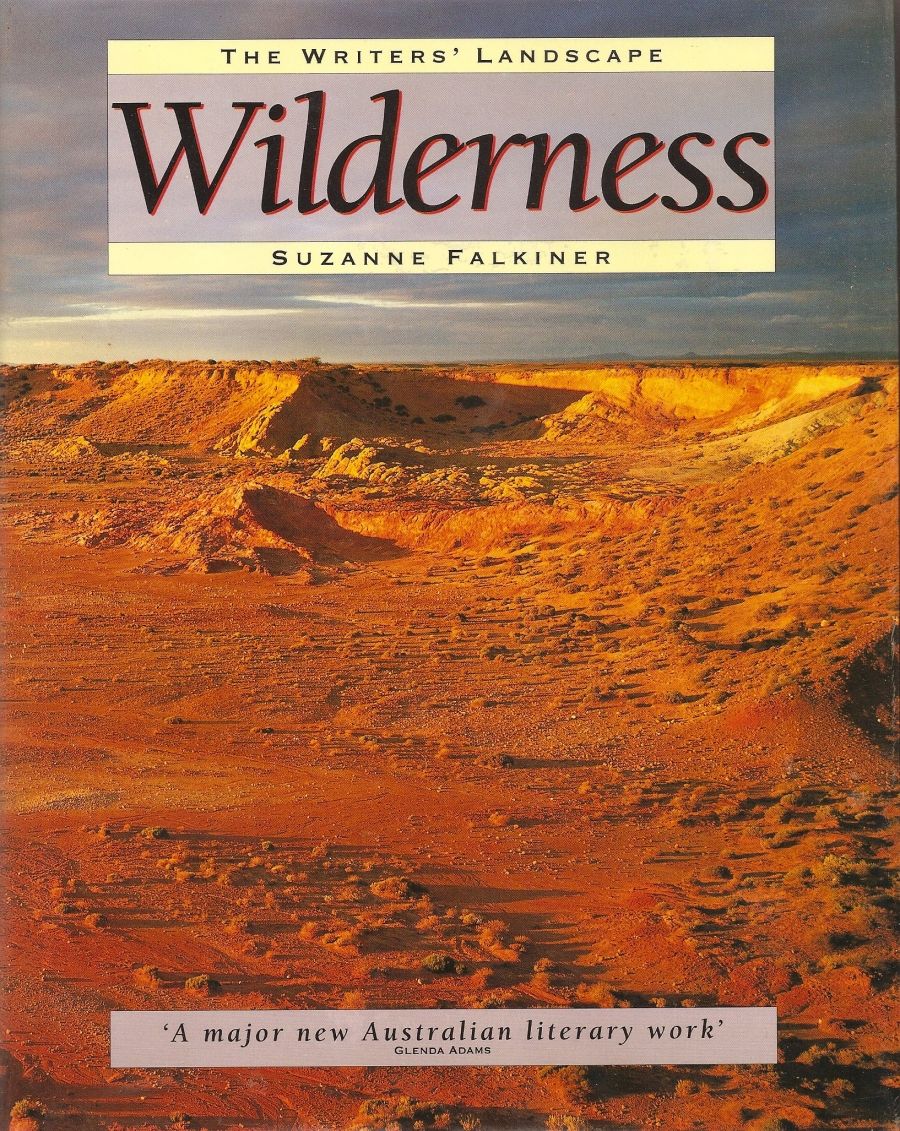

Suzanne Falkiner’s Wilderness is a garden of delights. This is one of the most imaginative, innovative, and useful books on Australian literary culture to emerge for some time. The book represents the first volume of a two-part series entitled The Writers’ Landscape, and Wilderness traces the influence of Australian landscape on Australian writers.

- Book 1 Title: Wilderness

- Book 1 Subtitle: The writer’s landscape, volume I

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon and Schuster, $39.95 hb

I must confess that when I first looked at this book I did so with some unease and trepidation. At a quick glance Wilderness looks like another exquisitely designed coffee-table book on Australian landscape, an expensive, large-format pictorial on the Timeless Land such as those displayed boldly in the ‘Australiana’ section of the big commercial bookstores. Why the unease? Well, because the 233 pages of text and the several pages of densely textured endnotes indicate that this is a scholarly and substantial work, and an enormous amount of intellectual energy and research has gone into this project. I felt at the start that the enterprise had been ill-conceived, that the coffee-table format and the high-level scholarship would probably cancel each other out, making this book fall on its face between these two entirely different markets.

By the time I became better acquainted with Wilderness I realised that my anxieties were unfounded, and that my ‘typical’ response of making rigid distinctions between commercial and academic readers and markets was itself challenged by this publication. It has built an incredibly solid and powerful bridge between the coffee-table and the ivory tower. I cannot imagine anyone who would not be delighted to be presented with this volume. Wilderness can be used for browsing, dipping into the text, admiring the stunning colour-plates, or for serious study, scholarship, or for inspiration for one’s own next book.

Wilderness represents an act of faith in the mythical general reader and also a belief that book publishing in this country can move a big step forward. The publisher has determined that the buyers of colourful Australiana deserve something more than what they are already getting. It is not enough to be titillated by summer scenes of Uluru and Bondi and to read an editor’s blurb at the foot of the page. On the other hand, perhaps Simon and Schuster have figured that Australian literary criticism could do with some sprucing up, with visual supports and better design. Perhaps they have decided that Australian literature is now sufficiently popular and entrenched that literary criticism can, or should, become popular as well.

This is not, however, simply pop. Aust. lit. crit. Suzanne Falkiner is not interested in a mere reader’s digest of traditional literary criticism but wants to revision the whole area and inject it with new life and metaphors. Wilderness is a remarkably rich sourcebook of Australian myths and metaphors of place. I am impressed by the overall design, by the way the author’s mind works, by her boundless enthusiasm for working and reworking our root-metaphors and our cultural history. Reading this enthralling study, we understand what Mark Twain meant when he said that our history reads like the most beautiful lies. Falkiner points out that early Australian experience was so full of mythical and narrative possibilities that there was little need for fiction as such, when life and landscape already presented the fantastic at every turn.

What we find here represents not only a new step in publishing, but also a new genre in Australian writing. Falkiner has drawn from novels, poetry, short fiction, explorers’ journals, literary criticism, historical documents – and she covers ‘mainstream’ writing, women’s writing, recent writing, Aboriginal writing – yet it is filtered through her own imagination, so that it becomes not dull reportage or academic commentary but an engrossing and stimulating narrative in its own right. This may be the shape of things to come, because I know of several projects in the pipeline that might attempt this kind of highly metaphorical, highly suggestive narrative criticism. We have had an enormous flowering of Australian literature over recent years, and now it is time to make sense of it all, to weave new syntheses, to arrive at new cultural understandings rather than to merely keep using the old ones to account for what is happening. And it is time for the Australian creative impulse to infect non-fiction as well as fiction, to allow the intellect and creativity, which are often artificially held apart, to come together in a new unholy alliance.

Certainly in this case the decision to write for a wider audience has had invigorating and positive effects on the conventions of literary scholarship in this country. Not only is the writing interesting, but the language is dynamic and wholly accessible. In Australia recently there has been some debate in newspapers and journals about the value or otherwise of highly specialised languages in academic writing. Academics have argued that special discourses are vital to the complexity and integrity of their disciplines, especially in the case of new or recent areas of intellectual enquiry. Journalists attack these rarefied discourses as outbreaks of ‘jargon’, and argue that they deny public access to vital areas of knowledge, creating small and ever-smaller circles of cultural power.

Suzanne Falkiner, in this context, is neither an academic nor a journalist but a committed and passionate public intellectual. Her language is open, accessible, jargon-free, but it is not simply impressionistic or humanistic in the way that postmodern academics deride. Although she describes Australian literature, her language is not merely descriptive. Although she writes to be understood, her writing is not merely conversational. She discovers ways to be complex and theoretical without employing overtly theoretical or abstract terms. She is confident about the English language, a confidence that reflects her career as a journalist and fiction-writer, and so does not require the added facility of new languages.

Falkiner’s passion is what D.W. Harding calls geopsychology, or continental influence. ‘If there is a soul to the Australian people, then, according to the work of many of the writers surveyed here, it is a soul shaped by landscape.’ This is her concluding sentence, but it is not just a rhetorical flourish; every page bears evidence of her concern for the soul of her country, and for how soul is fashioned and shaped by the land and by human experience. Twenty years ago literary critics wrote naively of the ‘influence’ of the land, never imagining that psychological and cultural forces conditioned and partly determined that influence. Today, with our postmodern emphasis on how Australia is ‘invented’ or constructed by social discourse, we have moved to the opposite extreme, we seem to forget the actuality of land, of place, and to concentrate upon the representation of place as a socio-political creation. Again, Suzanne Falkiner finds the creative middle ground.

She is not naive about continental influence, and is alert to the hidden subjective and cultural factors that determine how landscape is perceived. But nor does she forget the reality out there, collapsing everything into subjectivity and cultural politics. ‘Landscape’ is for her a mixture of out there and in here, a creative and necessary conjunction of subjectivity and objectivity. She treats landscape as a phenomenon, and phenomenology would appear to be the nearest theoretical model for what she has achieved here. But I feel professionally gratified and personally pleased by Suzanne Falkiner’s achievement, and hope that her example of public intellectuality will be followed by others and treated with the seriousness that it deserves.

Comments powered by CComment