- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

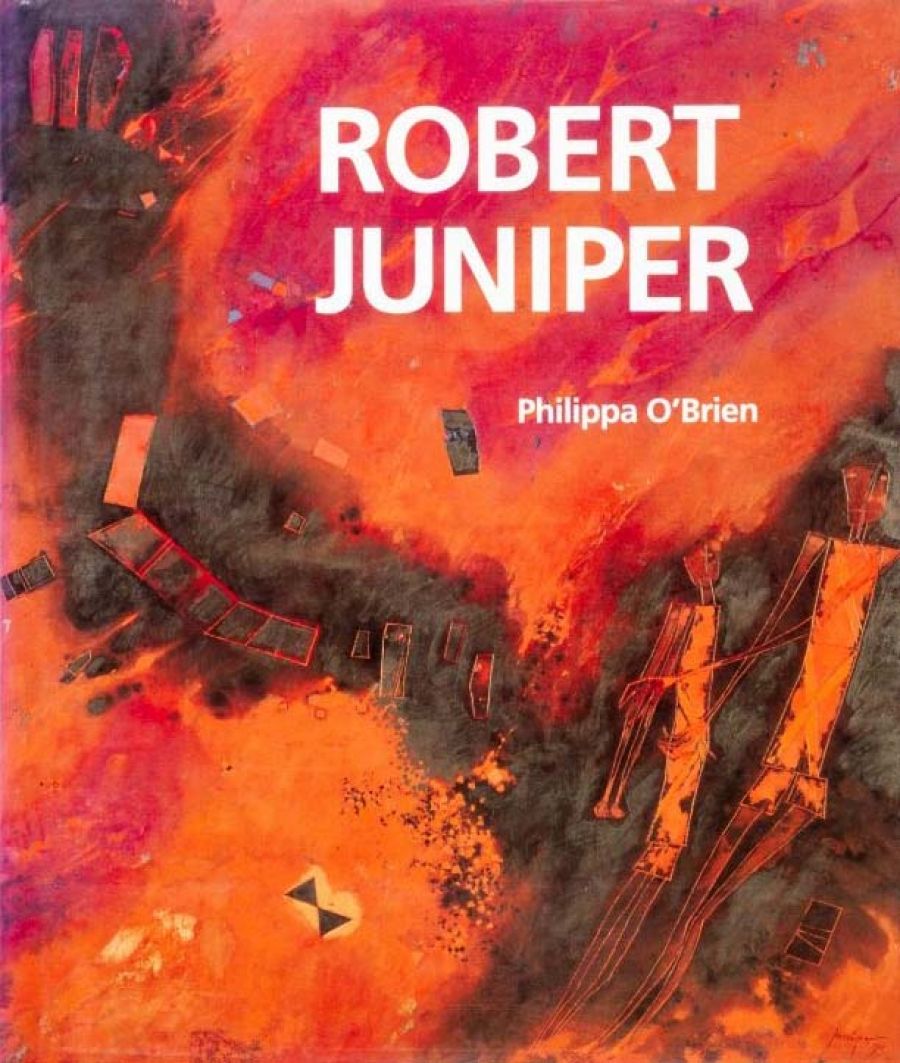

Craftsman House has contributed substantially to bringing our art map up-to-date with the simultaneous publication of a West Australian and a New South Wales art history. One on the work of Robert Juniper and the other on that of Salvatore Zofrea make interesting comparison. The first presents the style· of art one might expect to ensue from that great Western expanse of desert while the other challenges such expectations as stereotyped and clichéd. Juniper set out to depict the landscape and to heroicise it, as has been our tradition; Zofrea, according to Snell, incorporates Australia in the international tradition of art history.

- Book 1 Title: Robert Juniper

- Book 1 Biblio: Craftsman House, $80 hb

- Book 2 Title: Salvatore Zofrea

- Book 2 Subtitle: Images from the Psalms

- Book 2 Biblio: Craftsman House, $70 hb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/Archive/salvatore-zofrea-images-from-the-psalms.jpg

.

Beginning Philippa O’Brien’s monograph Robert Juniper, I was surprised by similarities of biography in Juniper’s early years and those of John Perceval. ‘Both men spent their early childhoods of the 1920s and 1930s at Merredin in the wheat country of Western Australia, both were separated from their mothers in childhood with a subsequent sense of abandonment, and both had a passion for stream trains. Here the coincidences end and I thought how Perceval would wish he had Juniper’s luck in travel ling to England to be reunited with his mother and then to discover as a young man works by artists such as Renoir, Sisley, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, and Soutine. These Juniper saw hanging in the corridor of the Beckenham art school where he enrolled in a commercial art course.

Philippa O’Brien takes the chronological approach typical of the art monograph and for ease of reference this may be the superior structure. While the text must serve the art it need not be less than it. This is not to denigrate her work but to query the chronological monograph form. The text can take on a creative character in its own right. Such a work may require an engaged reading rather than an occasional reference to be fully appreciated, but through the absorbed encounter the artist’s work is enhanced as is the reader’s satisfaction. Ted Snell in Salvatore Zofrea: Images from the Psalms deviates from the norm. He provides a substantial introductory essay, an interview with the artist, a sample catalogue raisonné and notes on each of the paintings illustrated. The change is refreshing and suited to Zofrea’s unusual programme: a series of interpretations of the first fifty psalms.

Ultimately, it seems, the reception of an art book is largely dictated by assessments of the artist’s work. O’Brien provides thorough analyses of examples from the Juniper oeuvre and traces the complex of sources which make up the work. She cites Klee, Fullbrook, Aboriginal art and a trip to Japan, among others, all of which are woven into the Australian landscape. ‘He loves the sinuous rivers that meander across screens’, she writes.

I find Juniper most interesting when he is at his least figurative. But abstraction takes a second place in his concern for the creation of a conservationist statement, this depending on a representative approach. According to Philippa O’Brien, Juniper was concerned to portray his own emotional response towards human insensitivity to Nature.

O’Brien also gives prominence to Juniper’s sculpture which is not well known, at least in the east. A six-metre high external piece cut from steel sheets, entitled Iron Thicket, is an interesting example, suggesting the shadow effects of interlocking plant leaves, despite the rigidity and severity of its material.

O’Brien provides an interesting foray into art politics as she outlines the negative effect the art system can have on the painter who is usually broke and therefore vulnerable to demands to prove his or her worth by producing on request. She tells of Juniper’s lifestyle, his expressionist house made of rammed earth, with the interior painted in yellow-pink ochre mixed from local clay and glue. Perhaps Juniper’s role in the wider context of West Australian social history will ultimately prove to be as significant as that of his artistic output.

Juniper won the Perth prize for contemporary art in 1954 and was included in the Recent Australian Art exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1961. He won the Wynn prize in 1980 and the Mona McCaughey prize in the same year.

Reproductions are placed in the second half of the book, after the text, and while one would not wish to bring about the demise of the glossy art book by increasing costs in a demand for uniform integration of text and illustration, there is no doubt that as far as ease of use and enjoyment of reading are concerned the two are preferably placed together. Reproductions do appear with text in Salvatore Zofrea.

Less excusable is the absence of footnotes. Robert Juniper comes without footnotes and Salvatore Zofrea without a bibliography, despite Ted Snell’s research. Publishers tend not to welcome the heavily footnoted manuscript but the absence of documentation can only demean the writer’s work, not to mention the continuing life of the book as a tool for further study. How information is derived does much to flesh out what is, after all, being presented as history. For example, Phillipa O’Brien often includes statements by Juniper. Although it is quite clear the words are Juniper’s they are neither introduced nor footnoted so there is no indication when or where he made them. The text moves so easily from a Juniper quote to the writer’s analysis that exactly whose view is being given is called into question.

Zofrea’s depictions are lively, funny, witty, and smutty but controlled and deeply thoughtful. His Australia is the Europeanised suburban Australia of New South Wales. To this he brings his recollections of a childhood spent in Borgia, Italy. His setting is the garden, just one symbol of God’s handiwork. For later psalms he uses the circus and its performing animals, and the brothel patronised by men we recognise as men we know. If the action occurs in the suburban home, the living-room is no longer mundane but becomes transformed into a place of intrigue as he focuses on the petty dramas that make up our lives. His narrative – the result of a pledge made in thanks for recovery from illness – is both personal and universal. For Zofrea all of life is religious. The daily dance is a trial, but one, as he puts it ‘that is (definitely) not churchy’.

Added to a melange of references from past art, from Cezanne to Stanley Spencer and Max Beckman, Zofrea brings his own humorous and human touches. One can hear the scratchy gramophone playing some awful tune in ‘Psalm Sixteen’ as the teenagers dance, engrossed in their sexual exploration. They are half naked but naive and tentative. Nevertheless, the boy’s boxer shorts open at the fly. Meanwhile the ash is about to fall from his mother’s cigarette as she sits and stares with a bored lack of interest in the goings-on beside her. Snell explains that Zofrea depicts the moment before the loss of innocence, and emphasises its significance in every life. Zofrea is a three-time winner of the Sulman prize.

An unfortunate aspect of both books is the absence of editorial rigour which would have eliminated such errors as all we writers make. This is a minor but unnecessary blight on books from one of the most important art publishing houses we have.

Comments powered by CComment