- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As part of his quest to gather information about the ‘famous Dr Warson Holmes Jackamara’ – a Detective Inspector of police, a government official, and the holder of a doctorate in criminology – an Aboriginal oral historian interviews an erstwhile Queensland real estate broker and aspiring politician, for whom Jackamara once worked as a ‘minder’. The transcripts of the resulting thirteen monologues comprise the substance of a novella which presents the reader with an object lesson about the dangers inherent in the greed for power – in hubris – and in white Australian’s failure to recognise the strength of the Aboriginal spirit beings. As such, despite what some might see as its overstrained mythicism, this work has a compelling, and uniquely Australian, quality.

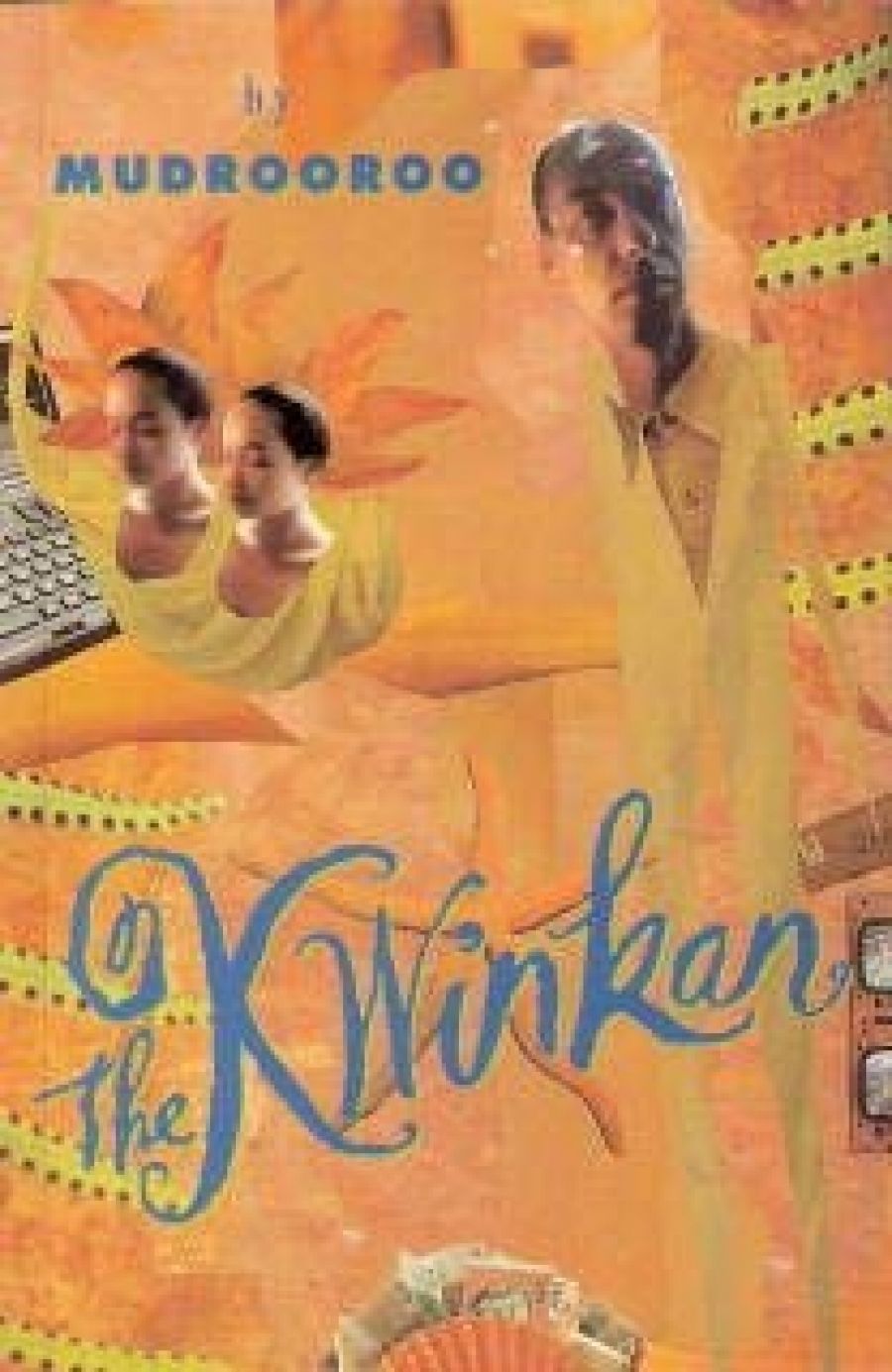

- Book 1 Title: The Kwinkan

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus and Robertson, $14.95 pb

It is indubitably the case that ‘truth’ is often stranger than fiction; but this novel’s plot frequently defies belief unless it is read on the level of the metaphorical. The interviewee seeks to divert his creditors by running for parliament. He ‘cashes in’ a favour with the prime minister, an old school chum, and is selected to stand for a ‘safe’ seat in the federal parliament, now located in the new Australian capital of Brisbane! The black vote being substantial in the seat, the Aboriginal policeman, Jackamara, is appointed as his minder and as his intermediary among the Aboriginal people. During one of their journeys into the outback, Jackamara recounts the story of the Gyinggi woman, who enchants men and drains them of their power, turning them into Kwinkan: elongated, stick-like beings who lose their nerve and are afraid to face the light of day and other men. On one level the novel can be read as an account of how this myth became translated into the reality of the interviewee’s life.

Defeated in the election, the interviewee is offered ‘reparation’ by his putative ally, the prime minister. He is to be sent to an obscure group of Pacific islands ostensibly on a ‘fact gathering mission’, but in reality to obtain an economic foothold on the islands. The interviewee is dejected until his unfailing opportunism elicits fantasies of how he might exploit the islands’ economic and sexual possibilities. Unfortunately for him, he has not reckoned with the presence on the islands of a combination of Japanese economic might and local ruling interests, personified by two women locked in a quasi-lesbian relationship: the vicious Riyoko Tamada and the seductive Carla, a ‘Gyinggi woman anxious to trap me’ – nor with the machinations of the omnipresent Jackamara. These forces combine to defeat him. When the interviewer finds him, he has become an obscure public servant about to suffer a nervous breakdown. According to the Aboriginal representation of his fate which informs this work, he has been converted into a kwinkan.

It soon becomes clear that the real subject of this novella is the anonymous interviewee, and the major theme his inability to learn the lessons of power. An opportunistic bungler, who had ridden high on the economic boom of the 1980s, this anti-hero is defeated by dark forces which he cannot understand in his ceaseless attempts to make a buck, and to win power and influence. If the interviewer had a hagiography of Jackamara in mind, all he obtained from this informant was a series of egocentric, and increasingly paranoiac and self-pitying, monologues about himself. Jackamara lurks in the background, only emerging as a somewhat shadowy figure, an ambiguous ally of the interviewee’s political enemies – and perhaps of the intangible kwinkan, the Aboriginal spirit beings – who, the latter claims, have long been bent upon his destruction. Although the theme of black-white relations is never stressed, the whole novel can be seen as exploring, in metaphorical terms, white Australians’ materialism and self-absorption and their inability to understand indigenous peoples in their own terms.

The book is fun, especially for an Australian versed in recent history and familiar enough with the territory to catch Mudrooroo’s allusions to some of the peculiarities of Australian culture and society; but its flaws – for example its contrived plot and its lack of character development – will prevent its achieving any more than minor status in Mudrooroo’s admirable corpus of works.

Comments powered by CComment