- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

People who have read John Banville’s Book of Evidence tend to pale and take on a manic look when they’re told that there is a new Banville out. When they learn that it’s linked with that earlier book, almost a sequel, their ears pinken, their lips tremble, and, most disturbingly, their fingers begin to twitch. At this stage, the holder of an advance proof backs away, calmly, as smoothly as possible, never turning until the door is reached. Then she runs, and they’re in hot pursuit.

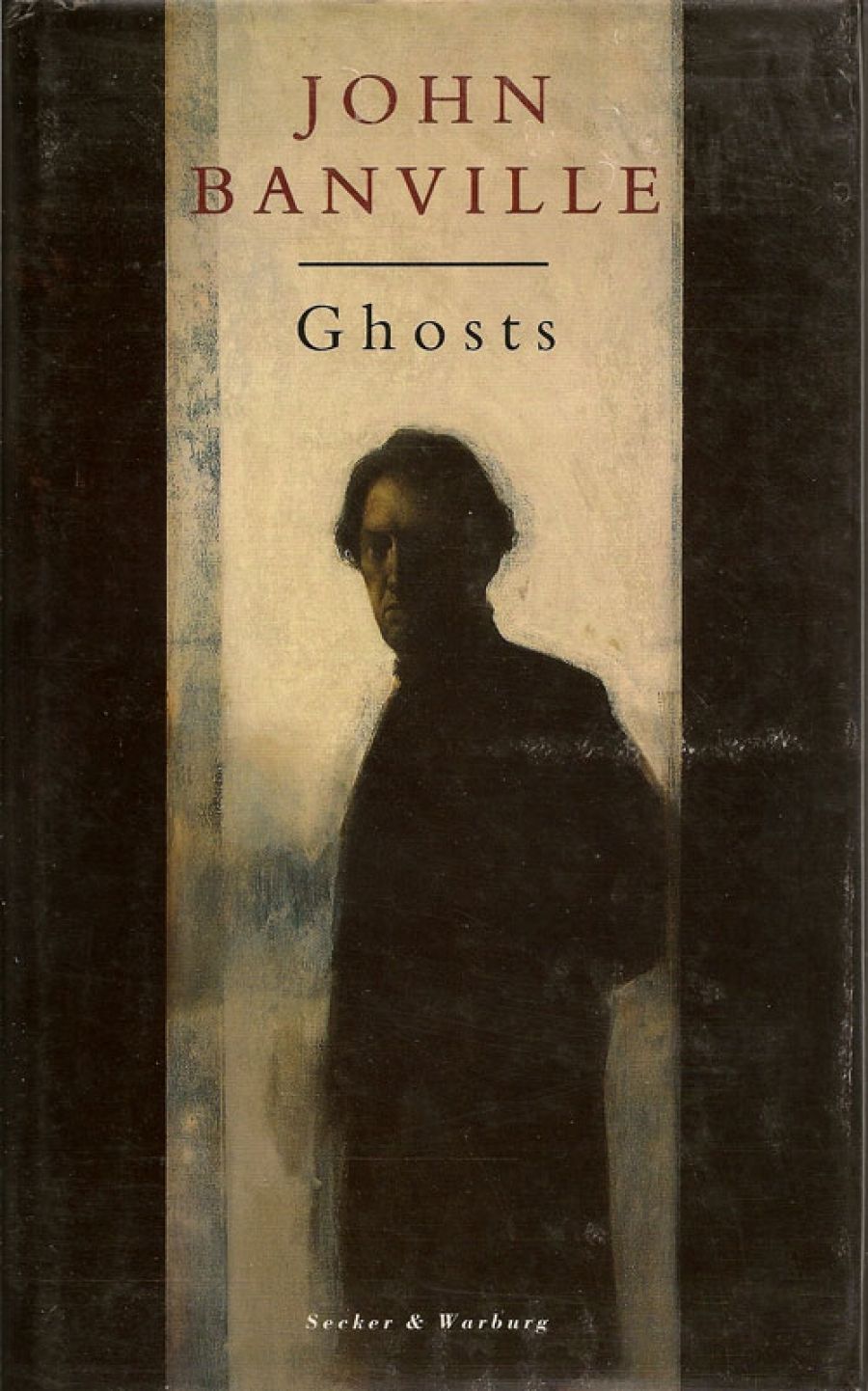

- Book 1 Title: Ghosts

- Book 1 Biblio: Secker & Warburg, $32.95 hb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zZWnx

In The Book of Evidence Freddie Montgomery murders for a painting, but only because it seems like an interesting thing to do at the time. Because Freddie tells the story we are controlled by his self-horror and his forlorn nihilism. In Ghosts, we are also controlled, but the control is less polite, both more light-hearted in its game-playing and more vicious in its teasing. The effect is, therefore, both less satisfying than the earlier book and more audacious. A sequel that owes everything and nothing to the earlier book, it can be read independently, but you’d be mad to miss out on the startling effect of the interrelationship.

Ghosts is set on an island where a ferry runs aground and strands a little group of day trippers. Felix (like Angela Carter’s Finn, like Mervyn Peake’s Steerpike) is lean and slithery, on the make, sexuality predatory, sly. Flora is soft and pliable, archetypal Spring and Desire in body, a miserable undefined person in spirit. And there are two despicable little boys, an alert but unhappy little girl, gross Croke who deserves a heart attack, and steely Sophie, foil and observer and photographer.

To the island they come, and to the house where Professor Kreutznauer whiles away his life in the company of smelly Licht and a sort of amanuensis, engaged in completing the Professor’s life work on the art of the nineteenth century Parisian painter, Vaublin. In one particularly dazzling chapter Vaublin’s art is carefully examined, and it’s as well to have a reproduction of Watteau’s Gilles nearby as you read this to compare and contrast with Banville’s repainting. Art intrudes into this book like slides dropped before a beam of light shone from a particularly unhelpful lighthouse. You wonder if you are in fact meant to avoid or hit the rocks.

The hand controlling the slide show is that of the amanuensis, and there are moments when we fear he might want to do more than simply control the light source. Things threaten in Ghosts, but the threats mostly dissipate as the time passes; people rearrange themselves upstairs, downstairs, out of doors, in kitchens, toilets, bedrooms. It’s a book of hints and possibilities, with all the action having taken place, as it becomes clear, in the past, and somewhere else. This island is not where things happen, but where things shift and sigh and bubble up before settling back down under a sea fog.

What happens here and now, in the time of the story, is that the narrator tells, he writes, he plays, as he says on the opening page, ‘little god’. He’s a self-indulgent little god, and he writes with a sombre mirth at his own self-indulgence, opening chapters with pompous flourishes such as: ‘Stealthily the day burgeons, climbing towards noon. The wind has died. On the ridge the oaks are motionless, dark with heat, and the air above the fields undulates like a blown banner.’

So do the rest talk like he tells us they talk? Are the little boys as vile as they are made to sound? Is Sophie so tragic? Is Licht so crackly odd and Felix so heinous? Yes, for as long as you’re following the narrator and his ghosts, and once he stretches out his pale fingers towards you, beckoning gently, you can only follow.

Comments powered by CComment