- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Guilt Edge

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The chief protagonist in Robert Wallace’s Art Rat is a character about as savoury as Sid Vicious at his worst. The Art Rat begins life as Glyn, then transforms himself into Matthew and finally Lupo, psychopath disguised as conceptual artist. With each new identity he sinks further into madness and obsession.

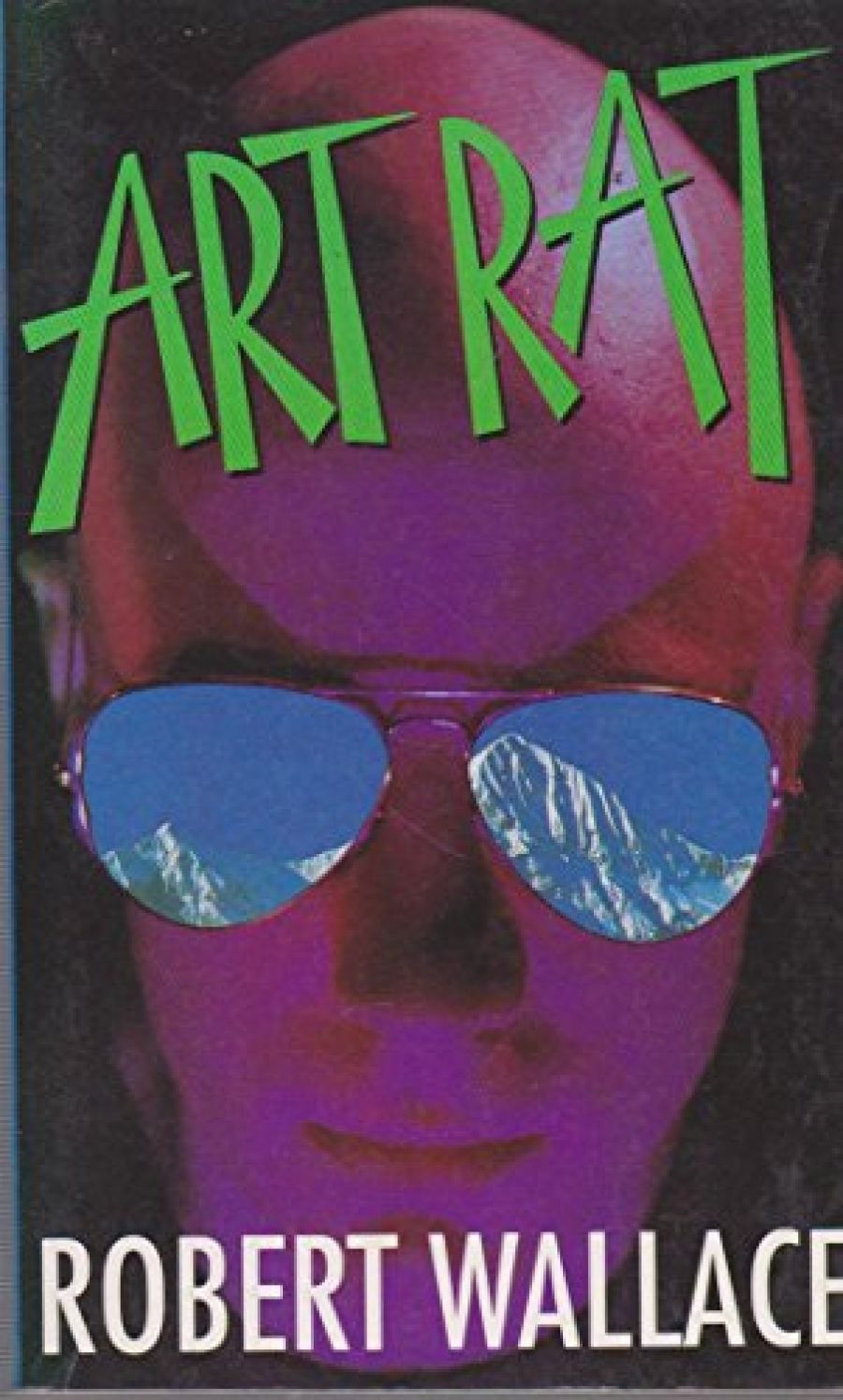

- Book 1 Title: Art Rat

- Book 1 Biblio: Harper Collins, $12.95pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: One Too Many

- Book 2 Biblio: Artemis, $14.95pb

Against the tranquil setting of an English country house owned by de factor stepfather Roy, Glyn commits his first crime and establishes a life-long target his de facto brother Matthew. His next crime leads to entanglements with the big boys and an escape to South America. Finally established as Lupo, the no longer fashionable artist who is nevertheless OK as a second ranker to be invited to an artfest in Sydney, Glyn gets his chance to get back at all of them – the stepfather, the step brother, the girlfriend of both who reminds Glyn of stepmother, all of them thorns in his side.

Art Rat succeeds much more than any of Wallace’s previous books. Its strength lie in its deft tracking of the long career of a psychopath, and in the way Wallace sustains at the same time a history of slightly incestuous family relationships. The mood of the book is thus quite different from the more conventional psycho-suspense which generally spans a much shorter time. The links between Lupo’s psychological state and his background are revealed gradually, with the final piece falling into place quite late in the book. The underlying tensions in the family group provide a suitably textured backdrop to Lupo’s violent career, and the vignettes of life in the art world are telling.

An irritating weakness is Wallace’s relentless use of fragmented sentences which creates the unfortunate effect of all the characters thinking telegraph style. Apart from this, Art Rat is excellent.

One Too Many is the second book featuring feminist private detective Francesca Miles. The book is based on the notorious series of murders of elderly people offensively dubbed by the press as the ‘Granny killings’. In One Too Many, the murders of wealthy women in Rose Bay in Sydney happen almost concurrently with a series of murders in Toorak. The modus operandi is similar, and the victims are female, elderly and wealthy.

Francesca Miles is called on for assistance by her friend Joe Barnaby, inspector of the NSW Police, who has been called in to help the Victorian Police in their inquiries. Together, Francesca and Joe examine the police records and with the help of the residents of an old persons’ retirement home and the relatives of some of the victims work out who is the culprit. Because they have no real evidence they invite all of those involved to afternoon tea at the retirement home and then tell the whole story in the hope that the culprit will give themselves away or confess.

These devices are timeworn in crime fiction, and well past their use-by date. No longer can a reader be convinced that a police officer will collaborate with a private detective or happily accept the assistance of a group of bereaved relatives, or set up something as improper as the afternoon tea scenario. Clan’s writing ability is certainly not up to making us suspend disbelief for even a moment and there is nothing much to redeem the unlikely plot in terms of interesting characters or gripping moments.

The local colour lacks interest, too, the writer assuming, in a somewhat snobbish fashion, that all readers are intimately familiar with the topography of inner-city Melbourne, requiring no more than a sort of Melways reference in order to set the scene. Thus, various locations are described merely by noting the route the characters followed to get there. Clearly not a book for a resident of, say, Mooroolbark or Hoppers Crossing, to whom the words ‘Brunswick Street’ are most likely completely unfamiliar.

Francesca the feminist detective is a disappointment by comparison with her numerous fictional sisters. Instead of leading by example, as it were, Francesca conveys the feminist message in a series of distracted and distracting homilies on any number of topics connected and unconnected with the plot: the position of women in society the inequities of the family court, the wrong thinking of The Silence of the Lambs. Inspector Joe is the usual audience for the homilies, and no small contribution to the unconvincingness of the narrative is his failure to beat Francesca viciously about the head with one of her own peppermint teabags out of intense boredom and resentment at being treated to so many insufferably pompous monologues on the position of women.

Comments powered by CComment