- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Contemporary Aboriginal writing, like Aboriginal art, is now so diverse that is impossible to talk about any one particular style. John Muk Muk Burke, whose first novel, Bridge of Triangles, has just been published, recently told a Sydney seminar for Aboriginal writers that they were no longer writing from the viewpoint of victims. He said they were survivors rising from the ashes of the invasion like the phoenix. Burke’s own novel is multi-layered, poetic and visually strong, with a structure informed by his study of world literature.

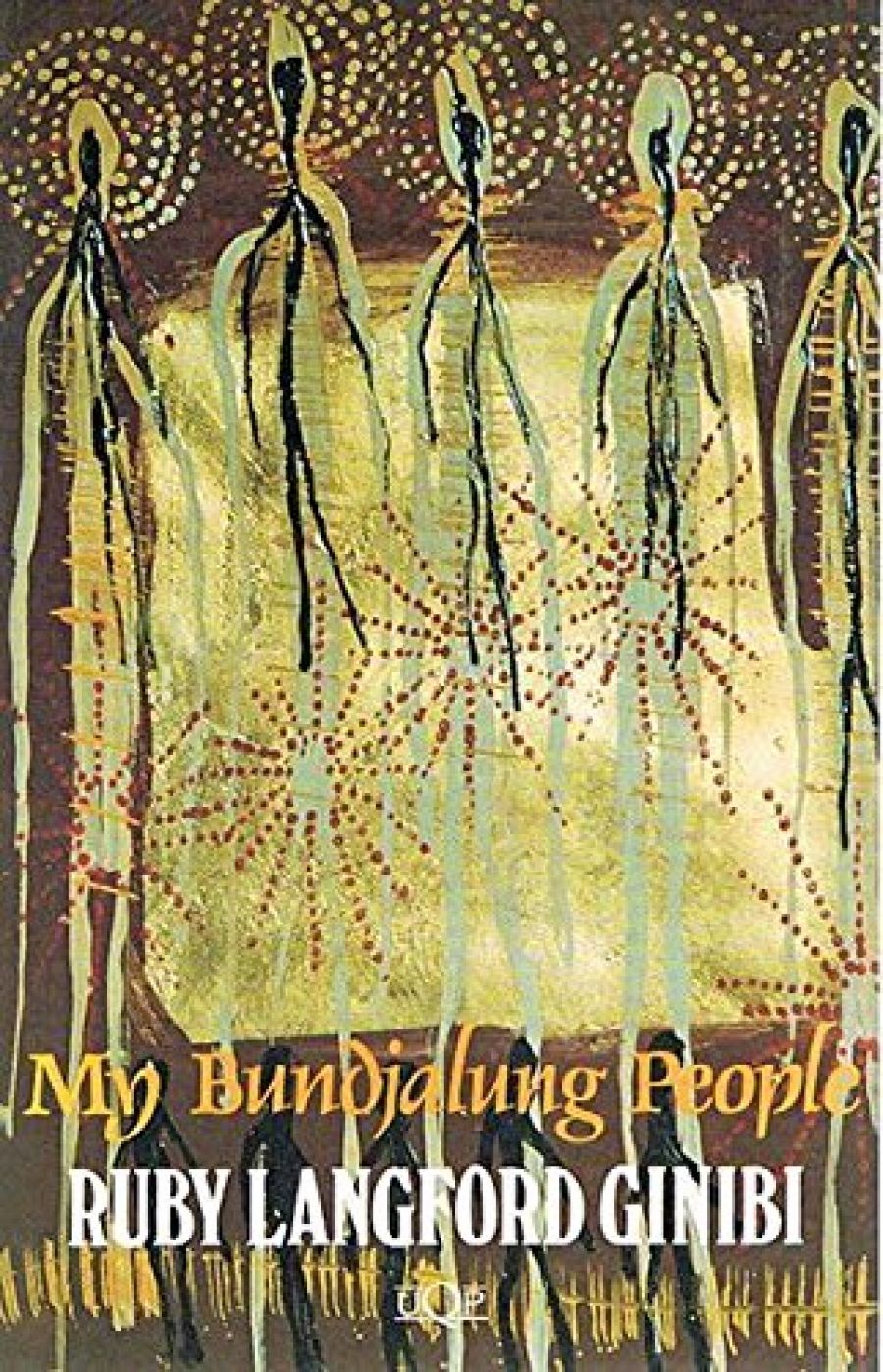

- Book 1 Title: My Bundjalung People

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $16.95 pb

Ruby Langford Ginibi told the same seminar that she writes the truth about Aboriginal lives, because ‘we are still being left out of the history books’. Her first novel, Don’t Take Your Love to Town was a raw gritty tale telling Koori life as it is. For some whites it was like a rite of passage into contemporary Aboriginal culture. Her second book, Real Deadly, was a collection of short stories and recollections which didn’t get the same exposure, but it too is jam packed with infectious characters, humour and a grim reality tinged with tragedy.

My Bundjalung People is different again. It is a spiritual and emotional odyssey, and a journey through Bundjalung territory which stretches north from Grafton to Lismore in New South Wales. The author grew up there, but hadn’t been back for forty-eight years when her father was forced to whisk the children away, to keep them from the grasp of the white welfare authorities.

But Ruby Langford Ginibi always wanted to go back to her country, and find her long lost relatives. So in 1991 she set out with Koori artist Pam Johnston at the wheel, on the first of five sojourns to Ruby’s ‘dreamland’. Ruby had put off this homecoming for so long because she was scared of reliving the past, and because she had spent the intervening years raising a family of nine children. She had also become an Aboriginal activist, invited to talk at public gatherings and doing her utmost to enlighten white Australia about its denial of black history.

At the beginning of her journey Ruby writes, ‘I wanted to travel back to the country where I was born to find my roots. It had been forty-eight years since I had left the mission at Box Ridge and although I was excited, I still had some qualms about it. You see, the memories I had of that place were very painful and I was frightened that my visit would bring them back to haunt me.’

In Box Ridge she encounters a terrible poverty but a resilient spirit that always keeps her people going. She also renews her bonds with her Aunt Eileen Morgan, an elder of her people, and a strong courageous woman who calls the middle-aged Ruby ‘girl’ and immediately makes her feel that she’s never been absent. The two women talk about their family history and Ruby records it all, on tape, and later writes down the conversation in a sort of ‘faction’ retelling of her travels in My Bundjalung People.

Everywhere they travel there are relatives Ruby hasn’t seen for four decades, and her questions reveal how these people worked and shared in the building of this nation. Many of the elders were employed by white land owners, such as the local rich Yabsley clan. In their house Ruby finds a photograph of her grandfather, Sam Anderson, who was a famous cricketer who would have joined Don Bradman’s team if it hadn’t been for the racism of the team selectors. Ruby interviews the descendants of Bruce Yabsley who once employed her grandfather, and challenges them about the ten acres that were given to her people but never actually handed over.

The visit to the old Kinchella Boys Horne outside Kempsey also brings a flood of painful memories. Ruby’s own son-in-law had been sent there for no justifiable reason. He was one of a hundred and fifty Koori boys who weren’t able ·to use their names and tells her, ‘They gave us numbers. I was number thirty-five’. The boys were given menial jobs and trained to work for whitemen, and if they did anything wrong they were punished severely. ‘Those who wet their beds constantly were made to sit out on the front lawn naked on an old shit pan in front of everyone to humiliate them’. The Aboriginal boys had no shoes, socks or jumpers and ‘we had to run around in the cold to keep warm. There was no one to look up to, or to protect us from these bastards. Most of the boys from Kinchella ended up in trouble or in gaol because of the treatment they’d received at the hands of those whites. They just couldn’t cope.’

My Bundjalung People also chronicles Ruby Langford Ginibi’s own inner journey, as Pam Johnston takes photographs of her people for an exhibition which Ruby is organising to celebrate their survival. During one of their pilgrimages Ruby gives a public lecture at The Lismore Club, which until that time had denied women entry. She ends her graphic summation of Aboriginal history with the statement, ‘We Aboriginal people survive in this country because we are a nation within a nation and we will never lose our Aboriginal spirit, no matter what the bureaucrats in Canberra do to us’. She also asks, ‘I wonder how long Australia can deny it has a black history?’

It’s a question Ruby Langford Ginibi keeps asking through her book, which deserves a wide readership. It’s also a question we need to constantly ask ourselves.

Comments powered by CComment