- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Desmond O’Grady is uniquely placed to interpret Australia for Italians and Italy for Australians. He grew up in suburban Melbourne, but as a journalist, biographer, and writer of fiction he has spent most of his working life in Rome.

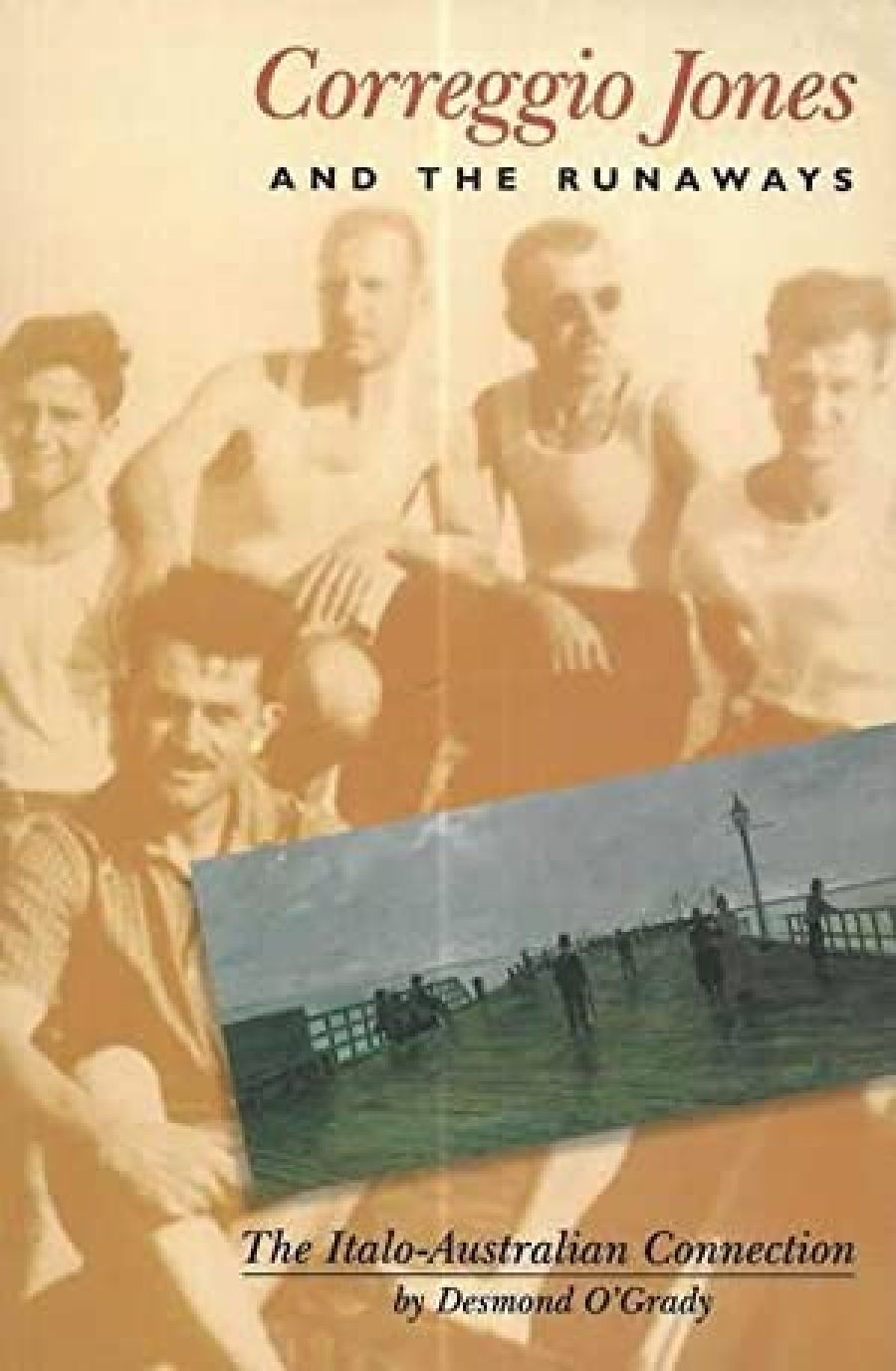

- Book 1 Title: Correggio Jones and the Runaways

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Italo-Australian connection

- Book 1 Biblio: CIS Publishers, $19.95 pb

When he went to Italy in the 1950s, Desmond O’Grady had no idea of becoming an expatriate, nor is it the term he would use to describe himself. His first trip to Europe might easily have been no more than the almost obligatory glimpse of the old world before settling down in Australia. But marriage to a Roman created his ‘complex fate’, and for more than thirty years O’Grady has lived and worked in Rome.

A career which began in Sydney, when he succeeded Douglas Stewart as literary editor of the Bulletin, was continued in Italy. As a journalist, O’Grady writes of Italian political, religious, and cultural matters in Australian and other international newspapers; thus he is constantly interpreting one nation to another. And in his short stories and plays, as well as the brilliant semi-autobiographical novel De-schooling Kevin Carew, O’Grady analyses Australian life with an unerring sense of its local qualities and idioms. Frequent visits have kept him in touch with a changing Australia; so too have all the Australian friends who regularly descend on Rome, and claim O’Grady’s time as guide and mentor.

The intriguing title, Correggio Jones and the Runaways, points to the two main stereotypes of those who change countries. ‘Correggio Jones’ comes from some verses by Victor Daley satirising the yearning romanticism of young Australian poets who find nothing at home worth writing about. Although Correggio (or Reg) Jones ‘dwells in Gander Flat/His soul’s in Italy’. The ‘Runaways’ have more practical reasons for changing countries: they are the Italians who came here in hard times, not for personal fulfilment, but to earn more than they could at home.

O’Grady’s studies of displacement set out to question the simple contrast between Australians seeking ‘their passionate true selves’ and Italians ‘passionately seeking a job’. For most of his subjects, the matter is more complex.

As the introductory section shows, the story of Italian migration began long before the government sponsored campaign of the 1950s. O’Grady cites many nineteenth-century Italian influences on Australian culture: among them the Florentine painters and teachers Girolamo Nerti, Ugo Catani, and Carmello Rolando. The most influential of all was Antonio Dattilo Rubbo, who arrived in the 1890s, established a studio in Sydney and taught for almost fifty years.

Gino Nibbi, who came to Melbourne in the mid-1930s, found it hard to choose between the two countries. After twenty-six years in Australia, he went home to die at Grottaferrata, which he compared nostalgically with Sassafras in the Dandenongs. Nibbi’s Leonardo Art Shop in Melbourne had crucial importance for Australian painters; Arthur Boyd, John Perceval, Sidney Nolan, and many others used to meet there, and Nibbi gave them their first glimpse of the works of Rouault, Picasso, and Braque in the splendid prints which he imported.

The novelist Martin Boyd, who spent the last seventeen years of his life in Rome, often thought of making the return journey, but concluded that he had left it too late for another change of hemisphere. Although in his restless expatriate life, moving from one pensione to another, Boyd shed most of his possessions, a photograph of Yarra Glen, where he had spent his boyhood, was at his bedside when he died.

O’Grady writes perceptively of Martin Boyd’s detestation of dependence and the toughness of spirit which belied his fragility. When his niece Mary Perceval wept at seeing how his last illness had diminished him, he rebuked her: ‘Don’t be soft, Mary, don’t be soft.’

In all the sketches and portraits that make up this absorbing book, Desmond O’Grady shows the intuitive sympathy which characterises the studies of Nibbi and Boyd. Most of his subjects are drawn from life, and based on interviews and research. But the strongest and most deeply felt piece belongs to the distant past. It tells the story of two Aboriginal boys who were brought to Rome in the 1840s by Rosendo Salvado, the Spanish Benedictine missionary who co-founded New Norcia Abbey in Western Australia. Pope Pius IX clothed the two boys as monks in a ceremony which seemed the fulfilment of Salvado’s dreams for a Catholic Australia, with Aboriginal as well as European priests.

Salvado was proud of his protégés; they disproved the popular belief that Aborigines could not be educated beyond the most elementary level. One of them, christened Francis Xavier as a signal of his missionary future, was soon reading Latin fluently. But the monastery records reveal a distressing series of illnesses; neither of the boys could adapt to the Italian climate and the monastic life. Francis died in Rome in 1853 after six years of exile. Alarmed, the authorities shipped the other boy home; he died soon after arrival in New Norcia, at the age of nineteen.

Some of O’Grady’s subjects choose freely; others are displaced by circumstance. They may be described as migrants, expatriates, exiles – or simply Italian-Australians. For the Aboriginal boys, O’Grady finds a tragically loaded word: he calls them ‘transportees’.

Comments powered by CComment