- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seaworld books

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

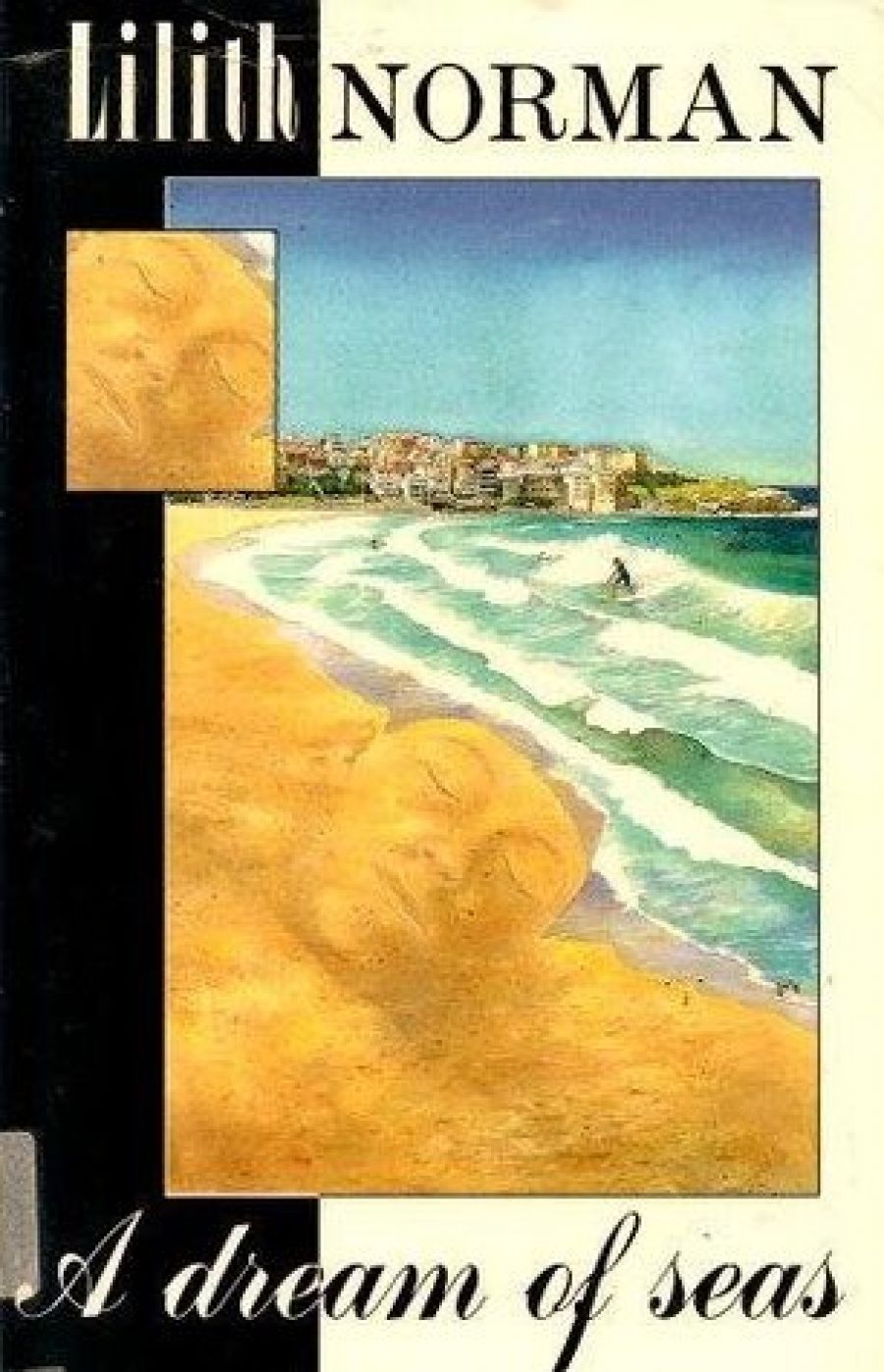

Lilith Norman’s exquisite novella was first published in 1978 and was an IBBY Honour Book in 1980. Set in a lovingly realised Bondi, the archetypal seaside suburb, the book packs a huge amount into its seventy-eight pages: life, death, love, grief; a question of focus; and, drawn in spare and beautifully controlled strokes, the disparate two worlds that touch at the shoreline.

- Book 1 Title: A Dream of Seas

- Book 1 Biblio: Red Fox/Random House, $7.95 pb

- Book 2 Title: The Secret Beach

- Book 2 Biblio: A&R, $9.95 pb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2022/Archive/French Secret Beach.jpg

Until he comes from the bush to live at Bondi at the beginning of the book, the boy’s contact with the sea has been minimal; now he knows it as his father’s new home, the logical last resting place of a stockman:

... swept away while trying to swim a flooded creek ... Swept down all the branching creeks, and over all the flood plains, and down all the rivers, to the sea.

Seen from the window of the grubby stuccoed flats where his mother is unpacking, the sea is reassuringly dotted with benignant seals, and even after closer inspection has revealed the seals to be board-riders waiting for a wave, the boy retains the double image, the reality and its magic counterpoise, and makes his vow: ‘I’m going to be a board-rider, halfseal and half-person. I’m going to be part of the sea.’

In sleep he enters the dreamworld of the sea, is born into the seal-world and starts to grow into a parallel maturity Awake, he enrols at his new school, acquires a nickname and a trio of friends, learns to swim and picks up a paper round – pathway to the board-rider’s freedom of surfboard and wetsuit – but not before he has made a seal-seeking pilgrimage to the zoo and seen in its sad, captive shadows an inkling of his destiny:

He had longed to see the magic of real seals, and now their shape was in him from looking; and he had looked at the real sea, and its magic was another kind of longing that was in him. And these separate longings flowed through him like two separate rivers, and he knew that the rivers must one day flow together before he was free.

Sleeping and waking the boy’s two worlds develop side by side, one fading as the other strengthens: he dreams through the school day; his mother finds a job, and through the job, a new partner. (In the seal colony the bull-seal rolls the importunate pup, and he survives unharmed.) Sharing the flat and his mother with roly-poly Yugoslav Frank – talking to a man again – the boy grasps at the fading memories of his father, renews his picture of him: ‘He was gone to sea whole, and he was there, waiting ...’ The young seal grows, learns how to handle the human hazards of the world, drift net and lobster pot, trawler and rifle, and sets out in a restless questing: ‘Somewhere up north was the home of his restlessness, and he was drawn there, steadily, like the weight on the end of a thread. Closer and closer.’

As the two streams of the story of the boy’s life come together, closer and closer, the reader forgets to breathe, paralysed by poignancy, but uplifted by the seamless skill with which Norman effects the union of her two worlds to bring a climax to this resonantly beautiful tale.

It is interesting that Maurice Saxby, in commending A Dream of Seas as ‘one of those rare elegiac fantasies which ... is both the face and the underside of reality, welling up from the author’s grasp of life and her own Dreaming’ (The Proof of the Puddin’ [1993]), invokes Matthew Arnold’s poem The Forsaken Merman, for it is a poem which informs all of Jackie French’s far from dissimilar new novel.

Like A Dream of Seas, The Secret Beach is set between the two worlds of, in this case, small country town land and magical undersea, and its main character is a similarly displaced youngster – a girl whose ambitious mother has dumped her with the father she last saw when she was three. Emily’s sense of dislocation leads to her friendship with Margaret, the town outcast, whose centricity resides in her claim to have spent ten years with the merpeople.

While hurt and prickly Emily makes acquaintances at school and hears, however unwillingly, a new side to the story of her parents’ marriage from her once-fisherman father, now anchored to a mundane fish and chip shop, she also learns the ways of self-sufficiency and the sea from Margaret, is entranced by her story of the seal woman, and, with the reader, gradually pieces together the tale of Margaret’s own experience in a magical maritime world as fragile and threatened as that the boy/seal inhabits.

Where the seaworld parallels the boy’s world in Norman’s story, the abandonment of Emily by her mother parallels Margaret’s abandonment of her merchildren in French’s, and while French’s adventure-story vehicle is cruder than Norman’s, and her relationships – particularly those between parents and children – less sensitively drawn, her conclusion is a far more positive one. The highly dramatic climax of the novel provides Emily with (teasingly, credibly equivocal) evidence for the truth of Margaret’s story and a final opportunity to choose life or death – commitment to the human world of land or to the yearned-for mysterious magic of the sea. Emily, like Margaret before her, and unlike Norman’s grief-stricken boy, chooses humanity: ‘When you’re human,’ the novel concludes robustly, affirmingly, ‘you can be everything, a creature of the land and sea and sky’.

Comments powered by CComment