- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Were it not for the timing, it would be easy to speculate that this richly evocative collection of pieces about music was the inspiration for Jane Campion’s glorious film, The Piano. So many elements of the film – the dominant image of the beached piano, the powerful undertow of sexual passion, even the unexpected violence-are present in this book in the most uncanny similitude. I should not be surprised since Carmel Bird has already displayed her uneasy fascination with the film in her dazzling essay ‘Freedom of Speech’ (in Columbus’ Blindness and Other Essays) and in her introduction to Red Hot Notes she admits that the film was a catalyst for the idea of various writers exploring ‘the complex feelings that surround, and embed themselves in, the human response to music’.

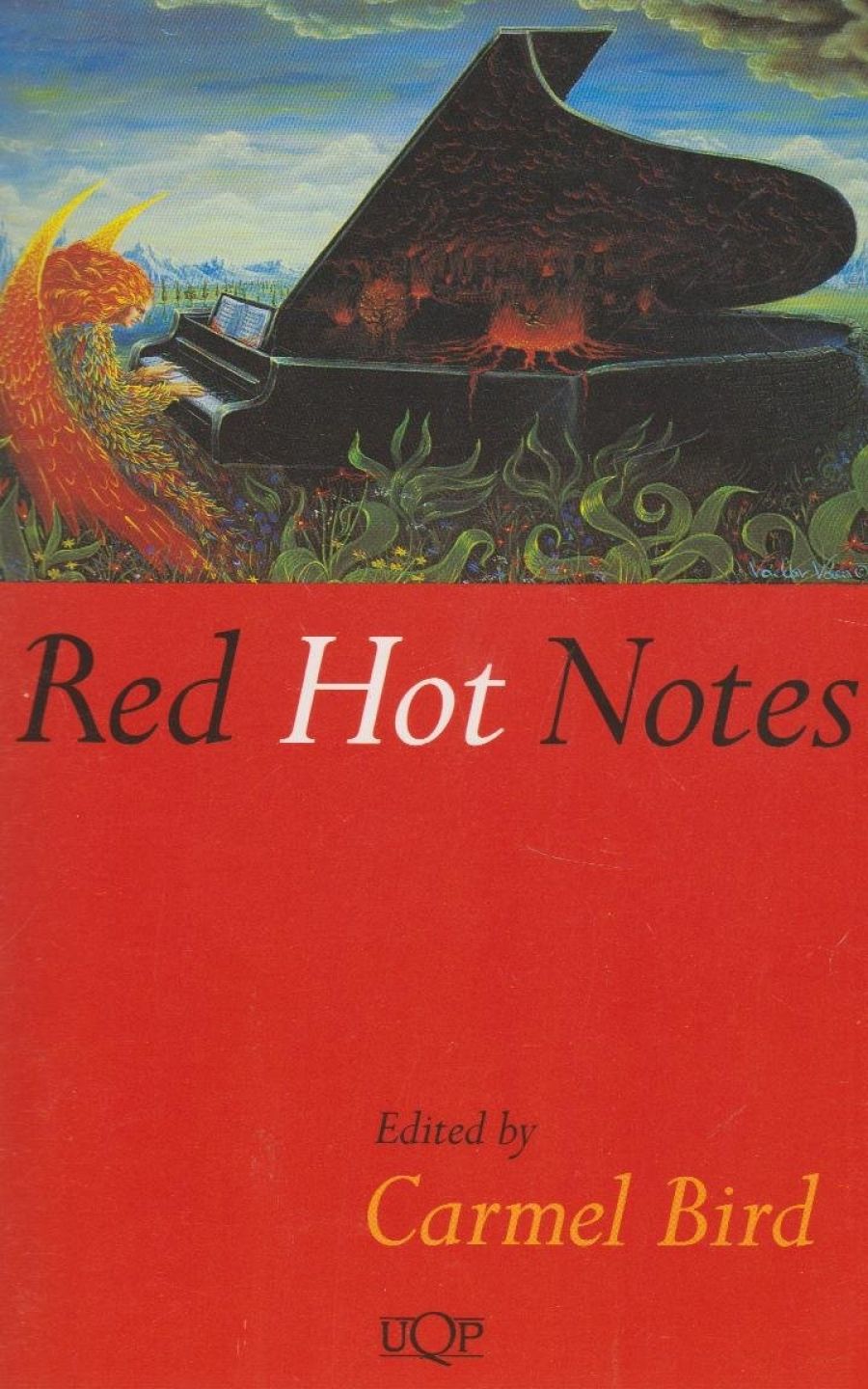

- Book 1 Title: Red Hot Notes

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $16.95 pb, 181 pp

What I find so uncanny is that the pieces which resonate with echoes of The Piano were written before the film was made. The most remarkable is Kerryn Goldsworthy’s ‘14th October 1843’, written in the composed yet shocking voice of an early colonial woman travelling through an alien and subliminally threatening landscape with her trappings of civilisation tied down to a cart:

This morning as we were packing up, one of the ropes restraining the piano broke ... As it gave way so did another which could not sustain the sudden Weight & the piano fell- slid-off the waggon. To our astonishment it landed upright among the stones but its travelling case was all smashed to hits down one side & Robert’s hand was crushed as he tried to catch & steady it from where he was standing near – with a great splinter of wood driving into one of his fingers. This is nor the first time the piano has hurt one of the hoys. I see I am writing about it as if it were a kind of Wild Animal –

Having jettisoned the piano in spectacular fashion, and remembering stories of other abandoned pianos, the narrator muses that perhaps

all over this country there are Dead Pianos – left on beaches – abandoned on tracks – pushed over cliffs-rotting in ruined huts & cabins ...

In her elegant essay, ‘A Pianoforte is a Fine Resource’, Marion Halligan quotes from a Mr McDermott, who wrote in 1874 of the grand pianos of the early colonists which’ lay exposed to all weathers on the beach’. She observes regretfully that if Campion had not made her film, she would have liked to have done something with their piano

Lying – I think I’d rather say standing, or huddling – on the beach. In such simple and heart-stopping image is a whole history. You can see the hope and the despair, bravery and finally, what really counts, the survival.

Halligan recounts how she liked to lie on the floor and look up the dresses of women at the piano. Like Baines, she too was ‘very interested in what went on under women’s dresses’.

In an extract from Peter Goldsworthy’s wonderful book, Maestro, published in 1989, the pianist, has, in some nameless violence, lost a finger.

But please, don’t let me persuade you that this book is a series of reveries on pianos or homage to Jane Campion. It is very much more complex and satisfying than that, although the piano is the overwhelming instrument. Featured also is the saxophone, the cello, the flute, the guitar, the gamelan; indeed, John Cranna’s superb story, ‘Visitors’, has an imagined chorus of instruments.

The modulation of the voices and the range of experience is as varied as the instruments. The collection includes the literary luminaries like Thea Astley, Helen Garner, Brian Castro and Gwen Harwood as well as newcomers Janey Runci, Bronwyn Minifie, Timothy Doyle and Chris Gregory. Some are better than others, but what I liked about the pieces was the intense evocation of feeling. The one exception is the story by Hal Porter. In her introduction Carmel Bird passes on to us the observation of Gillian Mears (here represented with a tantalising extract from The Mint Lawn) that ‘it would be unimaginable to produce this book without Hal Porter’s ‘Miss Rodda’. I entirely disagree.

Porter’s opening paragraph sets the baroque tone of his piece:

It was wet today. A vast voice poured in above the cataracting sea, over the sullied beach, over the screaming esplanade. Tamarisks tormenting themselves in the immeasurable monologue.

For my money there is no authenticity in this overwritten and overblown experience of suicide and the story sounds a distinctly discordant note among the finely crafted and finely tuned memories and observations of the rest of the collection. It is the one false note.

Comments powered by CComment