- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: International Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Once the scourge of the conservatives, some practitioners of cultural studies are starting to make the stuffed shirts of English Departments look like mad-eyed anarchists.

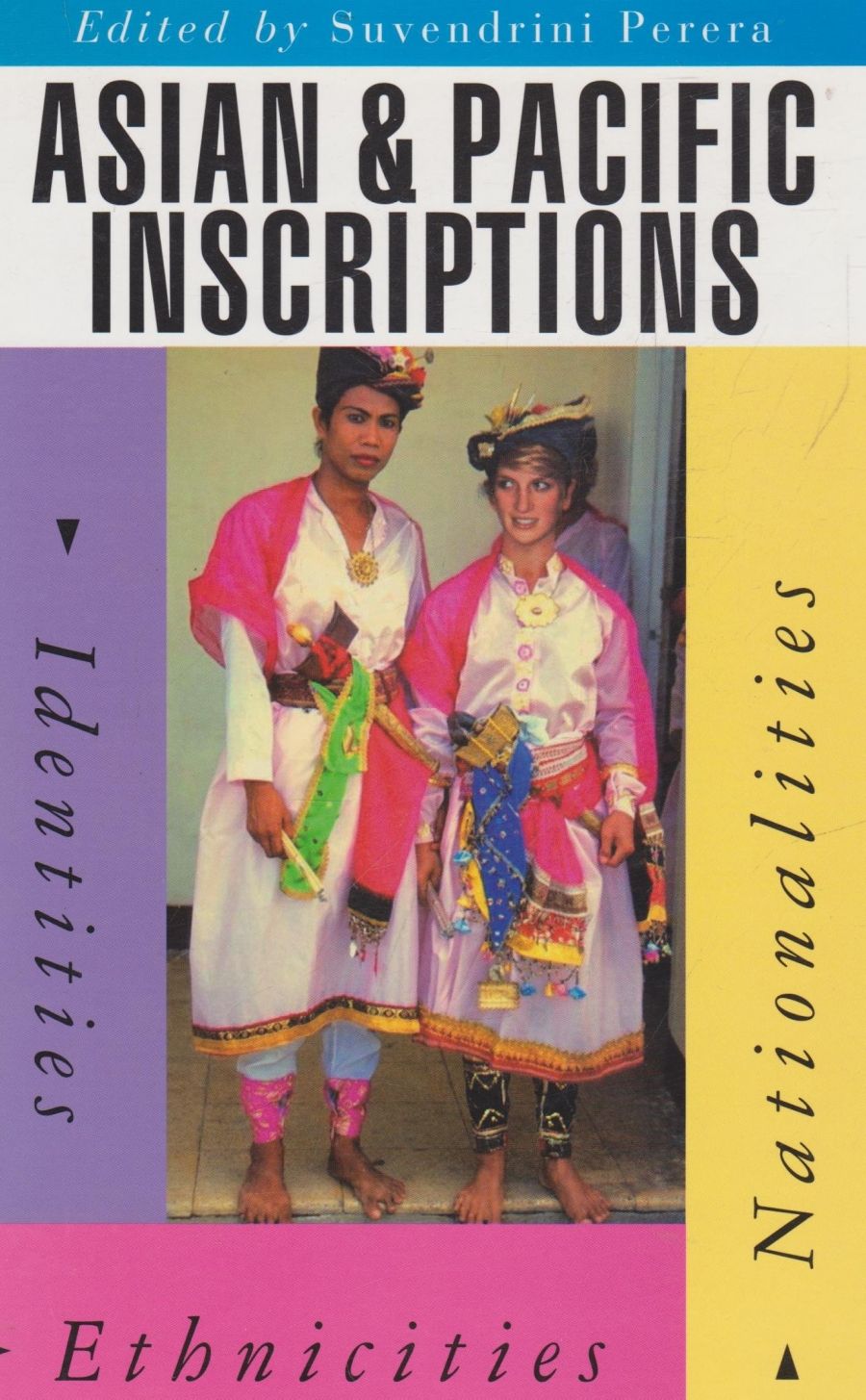

- Book 1 Title: Asian and Pacific Inscriptions

- Book 1 Subtitle: Identities, ethnicities, nationalities

- Book 1 Biblio: Meridian, $30.00 pb, 254 pp

The publicity accompanying Asian & Pacific Inscriptions notes that Perera received her PhD from New York’s Columbia University ‘under the supervision of Professor Edward W. Said’. And to think that the critic’s master narrative used to depend on the imprimatur of Oxford or Cambridge. But Perera is a gifted critic in no need of patronage. In her vigorous introduction, ‘Fatal (Con)junctions’, she compellingly questions the Asia industry in contemporary Australian culture and the ‘Utopian’ aspirations of its high profile promoters, like Donald Horne, who would remap existing cultural borders between Australia and Asia. This imperative, Perera notes, is symptomatic of the ‘preeminent desire’ of Western imperialism itself, as a ‘vast project of remapping’.

The ‘fetishisation’ of that geographically fuzzy and dizzyingly diverse place we call ‘Asia’ belongs, furthermore, to a nationalist agenda of the crudest kind. The Australian ‘interest’ in Asia is self-interest, rooted in chauvinism and motivated by economics. Asia has become, in what Perera sees as a ‘fatal’ junction of concepts of nationality and culture, the convenient vehicle in the manufacture of a new, updated, and upgraded Australia. This is a timely argument – the vacuousness of those who imagine new topographies of ‘Australia-in-Asia’ while blithely ignoring the realities within and across actual borders needs exposing.

But hang on, doesn’t this very book – authored largely by academics with a career investment in precisely this and associated cultural debates – itself owe its existence to the cultural currency of the Australia-in-Asia discourse? Understanding this, Perera tortuously asserts: ‘To call attention to the double-edged relationship between the book and one of the discourses in which it seeks to intervene is to recognise the complex rearrangements and negotiations involved in the process of rethinking the formation of collective and national identities … ’

Presumably this recognition is the reason why Alison Broinowski’s survey of Australian imaginative responses to Asia, The Yellow Lady, is lambasted in a review article by Foong Ling Kong as ‘very much a product of a particular establishment: white, male, middle-class, liberal, individualist.’ It must be – after all, it was published by OUP. (An alarmingly imperialist charter, printed in a 1926 history of the publishing company, is trotted out as some kind of evidence.) Obviously Broinowski should have searched for a more politically acceptable publisher. This sort of stuff cries out for an editor, presuming that role is not considered unduly suppressive these days. In the context of this article, it undermines a powerful argument about the cultural presumptions that impel Broinowski’s use of the adjective ‘Australian’, something about which all of us who work in the Australian Studies field constantly need reminding.

For donkey’s years, people whinged about the lack of a book like The Yellow Lady, the absence which was supposed to prove that Australia had a culpable lack of interest in Asia. And when one appears it is attacked, in this book, for being ‘Asia babble’, along with the festivals, conferences, and exchange programs that promote Australian awareness of its region. So much for years of work and research. It seems that part of Broinowski’s problem may also be personal. Writing from within the cultural, political, and racial establishment, Broinowski lacks ‘the liberatory and transgressive potential’ of the ‘intermediary space’ inhabited by the Kuala Lumpur-born, Melbourne-based Kong, who oxymoronically describes her cross-cultural perspective as ‘a classic deconstructive position’.

Perhaps it is unfair to single out Kong’s ‘Postcards from a Yellow Lady’ from a collection of fourteen essays. Indeed, Kong’s tenacious tackling of Broinowski over what she sees as the latter’s intellectual tourism just about makes it the book’s highlight (even if some of her commentary is derivative, as when she echoes Rana Kabbani in talking about views of Asia as ‘a space of possibilities’ and as an ‘escape from the dictates of bourgeois metropolitan reality.’) But there’s a certain arrogance about her critical practice and posture which is characteristic of the collection as a whole.

A critical self-awareness about the personal position from which one researches and writes is one thing; parading the right credentials from which most plausibly to theorise cultural relationships is another. So fraught has this business of Australians writing about Asia become that it is a wonder anything gets written at all. In Asian and Pacific Inscriptions, Dennis Altman feels it necessary to foreground his inquiry into the homosexual cultures of contemporary Asia by owning up to being ‘a privileged white Australian gay intellectual’.

Scholars working in the complex field covered by Perera’s Asian & Pacific Inscriptions will doubtlessly find it of real interest. The collection’s multidisciplinary scope is broad, covering topics as various as the production of an imagery of self in settler societies, to a critique of bureaucratic management of Aborigines in Victoria, to the confounding redundancies of familiar formulations of ‘East’ and ‘West’ in contemporary Singapore.

But it occurs to me that in the critique of the paradoxes ingrained in the sponsored development of collective ‘post-colonial’ identities, one new paradox has emerged. We all know what a satisfying target ‘imperialism’ is, and what a spectacularly fruitful critical resource it remains. But is there a new breed of intellectual imperialism at work in our universities? The maps of authority have been so radically redrawn that what was once the loudest voice in the Australian cultural landscape – that of the white male nationalist – has been well-and-truly drowned out. Fair enough, one might say, and about time. But are the new voices just as strident, self-justifying, and intolerant?

Comments powered by CComment