- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: And Two More Plays by Women

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Plays read in books can be nearly perfect works of creativity. The acting is superb, the sets and lighting are imaginative and breathtaking and the direction somehow manages to extract every subtlety from the text without ever becoming overbearing (and I haven’t even mentioned the costumes). In fact, some plays read so well on the page that that is where they deserve to remain without ever being made to endure the harsh reality of an actual theatrical production.

Composing Venus by Elaine Acworth revolves around three generations of women living in an Outback Queensland town and the forces of time and emotion that shape and change their lives. Set at the rear of one of those big stilt-raised Queensland houses, the play opens on a night in 1957 with a radio broadcast announcing that the Russian satellite Sputnik is set to pass through the night sky over Charters Towers.

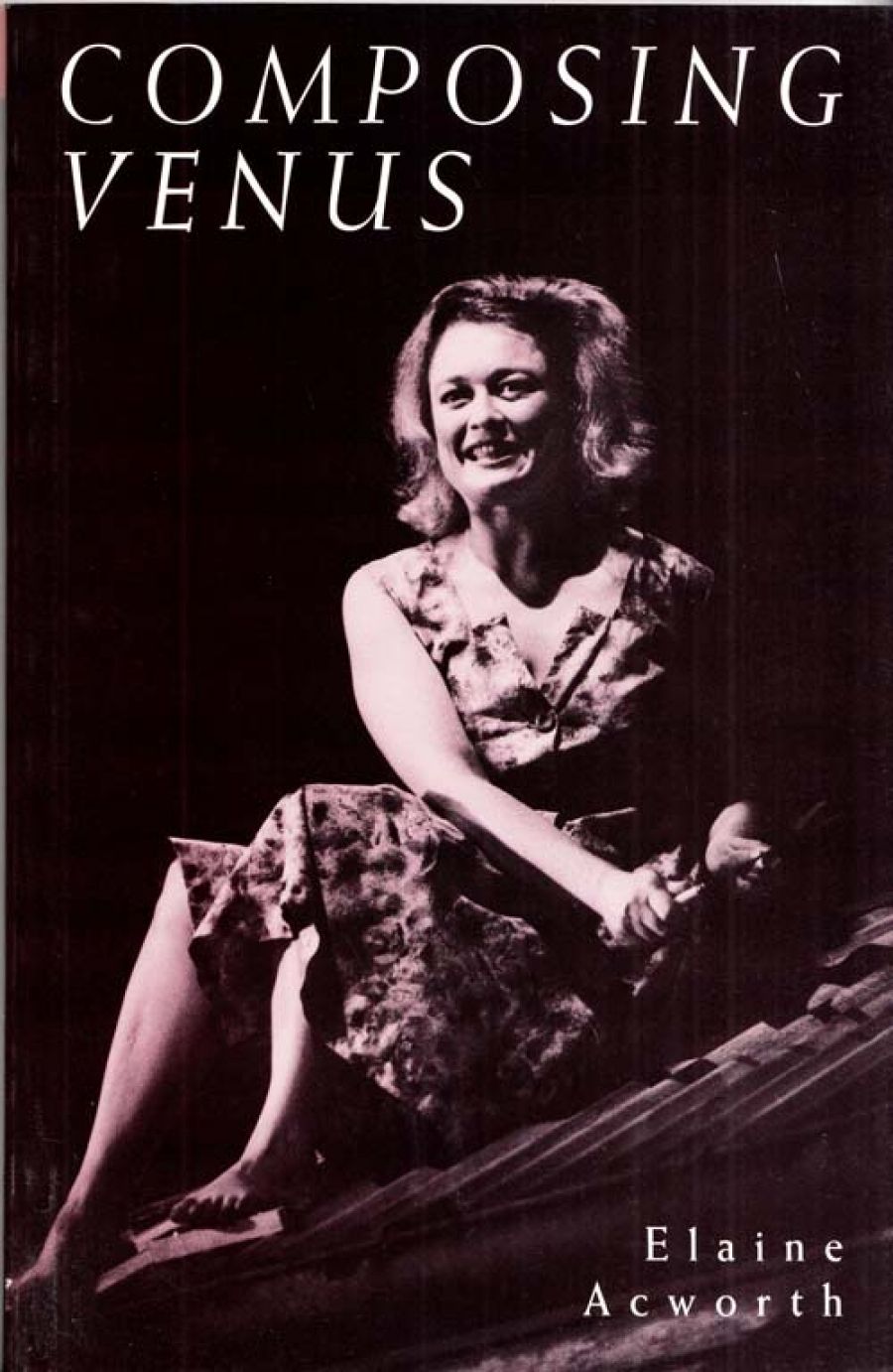

- Book 1 Title: Composing Venus

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency, $14.95 pb, 88 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

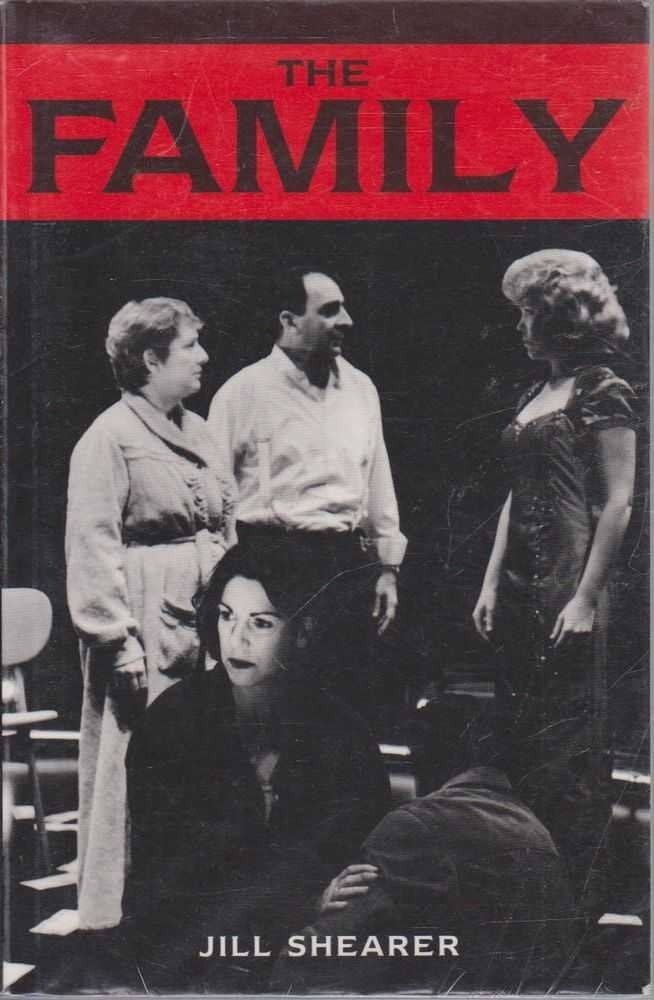

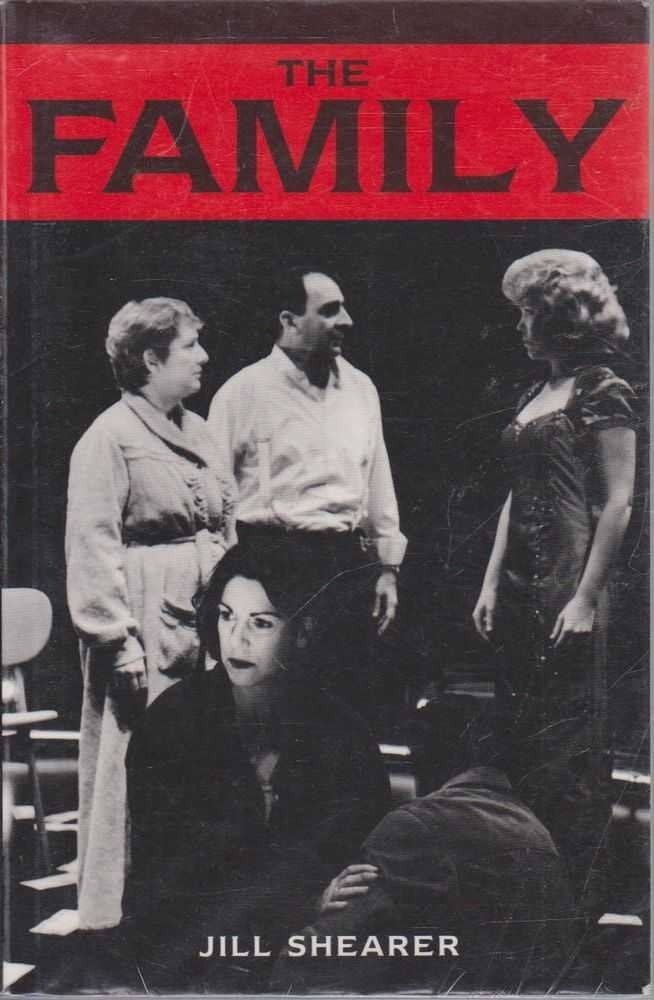

- Book 2 Title: The Family

- Book 2 Biblio: Currency, $14.95 pb, 80 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The dawning of this new era of rockets and technology is taken as a departure point not just from the familiar world this family of women has known all their lives but the structure and makeup of the family itself. Maeve Donnelly, the Irish matriarch, grandmother and defining force of the family of four other women, has gone missing. Siobhan, her daughter wails in a state of dreadful anxiety enough to get out of the place once and for all. ‘She’s dead. Dead and gone’, says Clivvy with a rather comic bluntness. Her mother wails again, ‘Heartless, just heartless. Don’t know where you get it from.’

From here, jumping back and forth in time, Acworth takes us on a dream-like journey over three decades to various seminal moments in the characters’ lives.

Maeve sets the tone back in 1925 by taunting a group of septuagenarian stereotypes from the Christian Women’s Temperance Union (that mystically emerge from an old gold mine) about such radical concepts as equal pay for women. ‘That’s right, love. All my life I’ve done a man’s work on the stations and never had a man’s pay for it’. The biddies (Mrs. X, Mrs. C, Mrs. L. etc.) are all shocked at the audaciousness of this ‘country crank, or Bolshie, mad as a coot with a mouth full of spleen and craziness’, as her far more conventional daughter, Siobhan puts it in a paroxysm of embarrassment. Hers is no ordinary family.

The women’s rite of passage theme marches on through depression and war, each of the women oppressed by the gossipy, narrow-minded nature of the fading town but ultimately dependent on it at the same time. Clivvy’s packing, a theme that continues throughout, is to take her prodigious if untrained pianistic talent to Paris. But, like the rest of the family, will she ever really leave the town?

Popping back and forth, in and out of time and reality, the family arrive at some sort of reluctant peace by play’ send but ultimately, the journey simply doesn’t work. Much of the characterisation is nauseatingly simplistic and the dialogue gushingly adolescent. It’s one of those plays where characters have lines that despite the deliberate blurring of reality, are simply not believable:

SIOBHAN: (Of her youngest) She’s not mine. She can’t be.

CL/WY: ‘Fraid she is, Mum. I was there when she happened. A thing of wonder out of bedlam.

For some reason, every character in the play is hemmed in by this peculiarly childlike stylisation that very quickly becomes irritating.

Strange, semi-operatic devices where the characters decide to suddenly ditch reality altogether are also employed. Although I’ve never seen them in their intended theatrical context, I kind of hope I never do.

Contrasting completely is The Family by Jill Shearer, a gem which had me rivetted from start to finish. It also concerns changes impacting upon a family (again in Queensland) and although less ambitious than the first play, is completely successful in what it sets out to achieve.

Frank is a long serving Brisbane police sergeant whose life has been shattered by his being recently named in an enquiry into police corruption. His family, particularly his wife Barbara and youngest daughter Emma have also shared the private hell of being suddenly shunned by a society they had always felt such a part of.

The eldest daughter and Dad’s pride and joy, Sarah, is a successful police officer in her own right. So successful in fact, that she has recently won a promotion to Internal Investigations, and when a shady police informer mentions her father’s name in association with a murky past she must make an agonising choice of whether to ignore what she suspects or start puffing together the pieces of a ghastly jigsaw puzzle.

Shearer’s dialogue is sharp, taut and real, even though the lines of reality are left skilfully ill-defined as a figure from Frank’s past comes back, spectrelike to haunt and tantalise him.

Families, and loyalty to families, is the ongoing theme of the play and is looked at from several different angles: from Barbara, who merely wants to keep it together, from Frank who feels he is about to lose it, from the younger sister Emma who is ignored by it and from Sarah, who must choose between loyalty to it and to her other family, the police force. Shearer combines a modern tale of a family in crisis with a riveting old-fashioned detective story that’s thriller in Itself. I just hope to see it on stage one of these days.

Comments powered by CComment