- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sea and Earth

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Fiona Capp’s accomplished first novel is pungent with sea-salt and urgent with the relentless momentum of the waves. It opens with the image of tsunami, a freak wave that grows from a shudder in the seabed to a wall of ocean which engulfs the landscape of the novel, an image which is recalled most effectively through the book to echo in metaphor the emotional upheavals of its characters.

These characters are strongly but sparely drawn: we meet them over a summer holiday season and learn little more of them than is necessary to give each motivation and convincing life. Hannah is a year into Melbourne University; commended all her life for having her feet firmly on the ground, she ‘dreams of walking on water’ and has come down the Mornington Peninsula with a secondhand surfboard to try to make the dream into one kind of reality. Marcus and his son Jake fled to the Peninsula from the Liverpool docks, putting distance between themselves and the pain of Jake’s mother’s death from cancer. Jake surfs under the jealous mentorship of a polio-stunted science teacher and Marcus collects the detritus and the distinctive treasures that the sea spews up along the tideline.

- Book 1 Title: Night Surfing

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $ 14.95 pb, 213 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

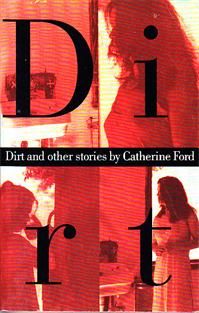

- Book 2 Title: Dirt

- Book 2 Biblio: Text, $14.95 pb, 186 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Ruben is proud of the cafe he and his wife Marie have made into the most popular haunt on the beach, but time has taken away his edge – a modern Pancake Parlour is siphoning off his trade and Marie is coming to the end of a tether that has long been frayed by hard work, smalltown boredom, and her husband’s tendency to demand too little of life. Marie herself, bulimic and longing to get away, has plunged into the life of the intellect. She lives for the day a week she spends studying secretly on the beach or in the university library, and for the times when she can tum the tables with a restaurant meal – a waitress waited upon.

It is a crucial summer for all of them: the tidal wave that shudders up from the depths and threatens to engulf them is in all cases a wave of self-recognition, a gathering understanding of their deepest fears and desires which must at last be faced and dealt with. Capp continues to parallel the emotional with the physical, so that Jake’s fear of long-term commitment, Ruben’s fear of the future, Marie’s painful rebirth as a different, separate person, are counterpointed by the physical fear and exhilaration of the surfers as they strive to harness the unpredictable energy of the sea. Similarly, Marcus’s need to make sense of his life after the death of his wife is translated into a desire to make sense of the sea’s enigmatic cast-offs, his sense of loss assuaged by a job which secures sand dunes against the destructive effects of time and tide.

Capp writes of surfing with an insider’s knowledge, sharing the fear and the exhilaration, and the haunting, upside-down isolation of seeing the land from the lonely vantage point of the sea. She is interested, too, in the contrast between surfing and surf lifesaving – a contrast which has an important plot-role in the narrative – seeing surfing as an activity which necessarily harmonises with its element while lifesaving opposes and seeks to subdue it. Capp sets the contrast, with romantic oversimplification, I feel, in class terms, giving the balance and connectedness of surfing to the salt-of-the-earth lower classes and the controlling drilling-and-marching of the lifesaving club to the despised offspring of a Portsea elite that is already heavily into power.

In spite of its simplistic stance on class, this clear and salty story with its clean-scoured prose and potent metaphorical framework adds a welcome new chapter to the Australian novel’s oddly belated exploration of the diverse cultures of ocean and beach.

If Night Surfing is all air and water with a bit of grit thrown in, Catherine Ford’s first collection of short stories has a contrastingly solid, earthy feel which is suggested by the title and borne out by the stories themselves. These are stories of earth, of the body weighed by its mortality, stories of no great lustre but of solid craftsmanship and shrewd understanding.

Ford’s characters, individually intense and often apparently focused on some deep, personal dis-ease, are almost preternaturally composed, and maintain a particularly detached and objective tone, a quality of heightened observation. Ford’s settings are cosmopolitan, her concerns universal, and plot almost incidental, hidden in the cracks between the details of characters’ lives, jostled by inconsequential anecdotes, conjured up in the reader’s mind just after they have turned their attention to the next episode. What happens, when it happens, happens far more in the head and heart and gut than it does in any of the events recorded on the page.

There are, nevertheless, some powerful and arresting images – a pair of little children ‘hung doubled over (a) plank like washing’, flanked by a trio of unrelated, fraught and coked up adults at a July 4th parade; the finger swollen with pus that makes a background for a sisterly meditation on relationships (‘ A Hundred Years as a Snail’); and, in the most memorable story of all, ‘The Remover of Obstacles’, set in Bombay, so many marvellous stills: in particular, the Indian waiter spooning rice into the obedient mouth of the main character, a young woman battered into compliance by India and melancholy; and the same waiter’s eccentrically graphic description of the fire that destroys his hotel.

There are one or two stories which seem, at least partially, less successful than the rest, particularly ‘Empty’ (which is, rather) and ‘The Last Vice-Consul’, where voices which need to be distinct blend into each other, but in the main Dirt impresses as a powerful and mature collection from an interesting new voice.

Comments powered by CComment