- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unimaginable lives

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Last year, two memoirs were published in Melbourne. Abraham Biderman’s The World of my Past and Mark Verstandig’s I rest my case should be read together and alongside Roman Visniac’s photographic record, A Vanished World. As intricate depictions of Polish Jewish life before the Holocaust and as intimate memorials to family and friends, they are monuments to the persistence of memory. But they also have an importance beyond that of individual recollections because of the contrasting insights they offer into the paths to, and resistance against, genocide in rural and urban Poland. Birdman, a survivor of the Lodz ghetto in a city once home to some 250,000 Jews, was incarcerated in a series of concentration camps before his ultimate release from Bergen-Belsen. Verstandig is one of the few thousand Jews who survived in hiding in the Polish countryside, which makes his account a relatively rare and important historic record.

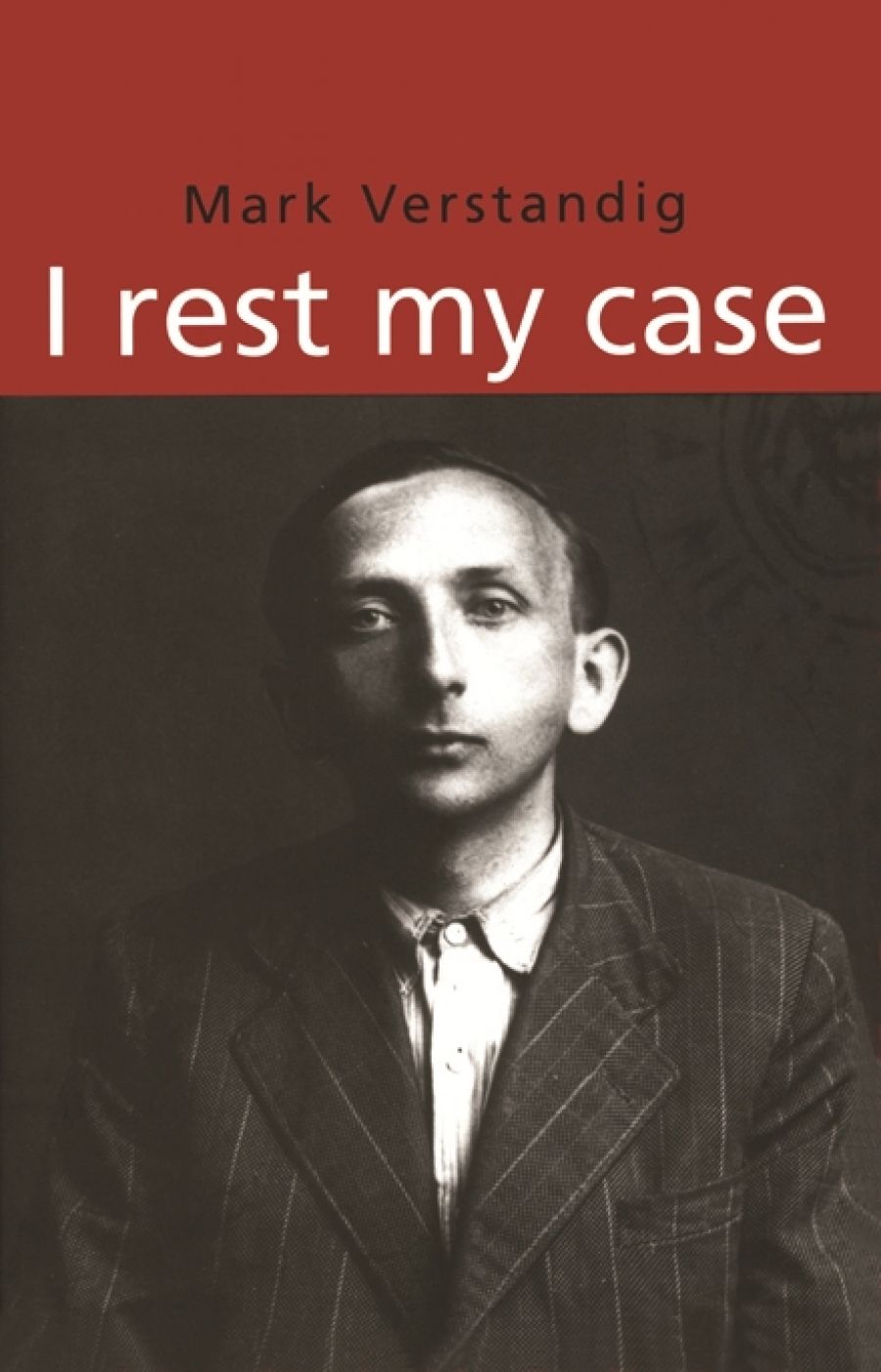

- Book 1 Title: I rest my case

- Book 1 Biblio: Saga Press, $16.95 pb, 290 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Born in 1912, Verstandig grew up in a Hassidic household in Mielec, in Western Galicia. He writes with intelligence and wit about everyday life in his shtetl – shaped by religious rituals, scholarship, factions, and disputes – in what was still, in many ways, a pre-industrial society. He graduated from university in cosmopolitan Cracow to be a smart and cocky young lawyer practising in his home town. In his own transition towards a more secular outlook and lifestyle, Verstandig conveys a sense of how modernity probably would have slowly transformed the pattern of existence in rural Poland. Instead, its destruction was rapid, fiercely brutal and comprehensive.

As occurred elsewhere in Europe during the 1930s, the erosion of already limited civil rights, institutionalised discrimination in the professions and increasingly open hostility, further separated Jews from the rest of Polish society. But nothing could have prepared them for what followed the German invasion. For instance, on the eve of the Jewish New Year, 13 September 1939, many of the Jews of Mielec were herded by the Gestapo into the town’s synagogue and its neighbouring buildings and burned alive. Similar ‘isolated’ acts of terror occurred across Poland. Then, in March 1942, the Nazis began instituting the Final Solution. Within only eleven months, by February 1943, eighty percent of all who would die in the Holocaust or some four and a half million Jews – including most of the Jews of Poland – had perished.

Verstandig was thirty when he escaped deportation from Mielec. His brother’s family fled to Russia. His parents perished. For the next two years, he and his future wife were hidden by Polish peasants, often surviving only by sheer chance. Several thousand other Jews in German-occupied Poland found similar refuge or became – partisans threatened more by the anti-Semitic Polish underground than by the Germans. Could Jews in the Polish countryside, with its close-knit communities, have had a better chance of surviving in disguise or in hiding? Verstandig shows, without doubt, that had Christian Poles behaved like the Danes or the Bulgarians rather than co-operating so vigorously with the Germans, many more would have escaped.

A few ‘righteous Gentiles’ chose to help Jews at enormous risk to themselves and their families. But more often, former associates turned their backs on, or denounced, Jews they once knew well. Peasants delighted in hunting out Jews and offering them up to the Polish partisans, police or the Germans. Others hid Jews only in return for payment, some later robbing and betraying their victims. The climate of violent anti-Semitism survived the end of the war. Poles continued the work of creating a Judenrein – ‘Jew-free’ – Poland by legally expropriating, persecuting and even killing Holocaust survivors, in the Kielce pogrom in 1946. (Biderman comments on the extraordinary phenomenon of the widespread survival of anti-Semitism – without Jews – in Poland today.)

Inevitably, implicitly, Verstandig’s book revolves around the question of why some – but so few – Christian Poles resisted and so many actively participated in this slaughter. With his formidable talent for harbouring facts, Verstandig is at pains to provide a very precise (and morbidly exciting) account of what wartime pressures made of those he knew – professors, judges, fellow lawyers, fellow Jews. They were pious, cowardly, fearful, honest, indifferent, brave, foolish, treacherous, malicious – fellow travellers, collaborators, resisters. He creates a tapestry of those minute personal choices, acts of complicity or resistance, which either pave the way to Auschwitz – and later to Srebednica – or away from them. Like Biderman, Verstandig predominantly blames the Polish Catholic Church for fostering, enflaming and exploiting anti-Semitic feeling amongst relatively uneducated Polish Christians, preparing the deep cultural foundations on which the Germans then established their industrial system of extermination with ease. Indeed, with its depiction of the powerful role played by the Church in paving the way to genocide and through its rendering of the full complexity of interactions between Christian and Jewish Poles, this book provides a particularly strong antidote to the superficial and distorted ‘fictional’ representations of similar communities in the Ukraine in The Hand That Signed The Paper.

Verstandig is a survivor, inevitably deeply marked by trauma. Unlike Biderman’s mesmerising Yiddish storytelling – weaving backwards and forwards in time piling on anecdotes, writing simultaneously to provoke memory and to escape what is remembered – I rest my case is linear and restrained. Devoid of self-pity, it also provides few glimpses of a reflective inner life. There is little mention of faith or of what Judaism meant to Verstandig after the war. It is a pity, but perhaps revealing, that the period from 1949 to the present is covered in only twenty pages. Arriving in Australia in 1952 – ‘we had heard that sports results were the only news which interested Australians. We thought that this country must be tailor made for refugees like us who wanted to forget the nightmarish past’ – he then established a successful clothing business. Yet, poignantly, the entire book displays his talent as a legal advocate with a strong sense of justice. The title suggests where his real sense of self might still rest, with a career and in a world destroyed fifty years ago.

There is a tragic inevitability about Holocaust memoirs. They describe their extinguished pre-War communities, a descent into almost unimaginable suffering, the author’s ‘escape’. Reading them offers voyeuristic access to processes of systematic degradation, to the anti-worlds of the ghettos and the concentration camps. They hollow out your sense of the solidity of ‘civilised life’. Why read such books? Perhaps because if we can begin to see, in close detail, the steps which led to the death of so many individuals and their communities, we might be provoked to act against similar threats elsewhere. These books indirectly encourage us to reflect, for instance, on how it is that we have ‘accepted’ the conditions faced by most Aboriginal communities of the West’s lethargic response to ‘ethnic cleansing’ in Bosnia.

Comments powered by CComment