- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reviews

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Guns, No Roses

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The good old days (bad old days?) of young adult fiction are gone. A couple of decades back it was impossible to imagine a reputable mainstream publisher producing a book for older children which has been supported by the Literature Board of the Australia Council and whose plot revolves around drug-taking (casual and accepted), violence, murder, abduction and rape. This is what The Enemy You Killed is about. The question is, does it more accurately depict real life than, say, an old-fashioned genteel novel like Swallows and Amazons? Perhaps it depends where you live. I’m not convinced that teenage gunplay with live ammunition is necessarily more ‘real’ than messing about with boats. At least in Australia. There is more than a whiff of the tabloids around the melodrama of The Enemy You Killed. It tells of a fifteenyear-old girl, Jules (Julia), who lives in an unspecified country town which lies close to a state forest dissected by a steep gorge. In this forest, mostly at weekends, many of the local young people have for many years been playing wargames dressed in combat gear and using not only air rifles and home-made explosives, but sometimes real combat weapons. The Tunnel Rats stalk The Rebels and vice versa, and a successful ambush is the ultimate thrill.

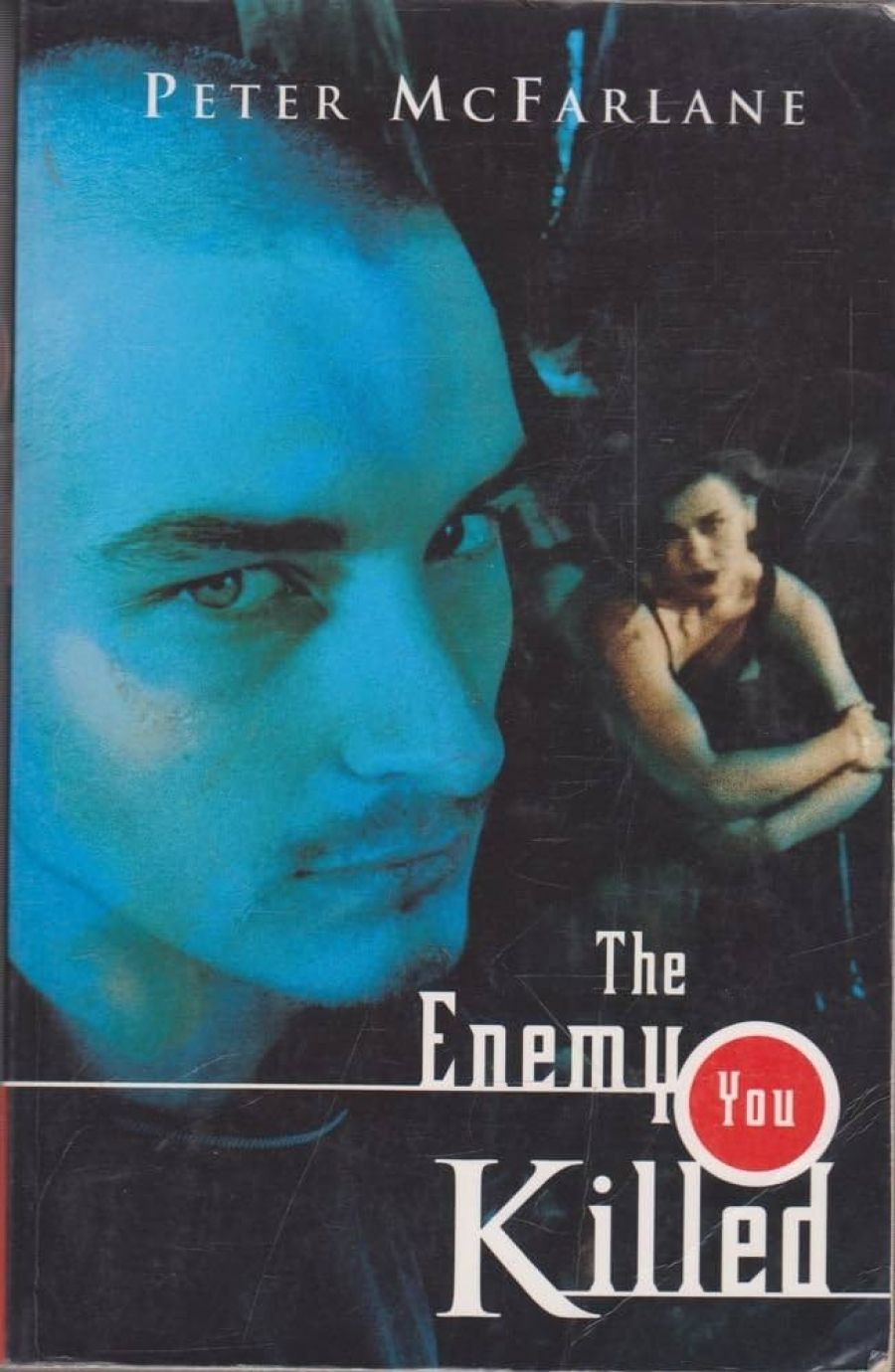

- Book 1 Title: The Enemy You Killed

Jules joins Jammo and other schoolchildren for wargames on a long weekend, and after increasingly lurid events their group is ambushed and Jammo is shot dead through the head by an invisible sniper. The consensus is that it was a tragic accident resulting from these foolish teenage games, but the reader (unlike Jules) knows it was murder. Heartbroken Jules freaks again, despairs, returns to Wade, and is raped, abducted and held underground in a denouement that will remind some readers of John Fowles’s The Collector. But her fundamental feistiness finds a way out, and normal social values finally triumph over the horror welling up from society’s dank underside.

In synopsis it sounds pretty bad, but it is both well written and well characterised. Eight or so teenagers, and several school teachers, are vividly evoked as separate beings with flaws and good sides, even the local hoons who delight in breaking up parties with baseball bats. The book is morally on the side of the angels, but never preaches, doesn’t get too upset about teenage sex or dropping acid, and insofar as it has a voice, it is the voice of the cool adult who understands teenagers, rather like the voice of the author’s apparent alter ego, school counsellor Danny Djurasevitch.

There are times when it reads almost like a template produced for a writer’s workshop to show how to get it right. You want symbolism, not too thumping or obtrusive? Then look at the clever use made throughout by the Wilfred Owen poem from which the novel’s title is taken. You want to know how casually and succinctly to introduce a large cast’? Read about the heavy-metal gig in chapter two. You want to know how to write the kind of graphic prose that tugs you interestedly through the story without drawing attention to itself? Look at McFarlane’s sentences, noun and verbheavy, light on adjectives and adverbs, usually quite short.

However, though one day Mr McFarlane might write a first-rate novel, I don’t think this is it. It is somehow factitious, too obviously made, too neat. Take the rope bridge over the gorge, mentioned repeatedly, as if it is going to be important to the plot. Well it isn’t. It’s there for one reason only. It provides the author with an appropriately resonant last sentence: ‘“I want to cross to the other side”, she said.’ Arguably, someone who has been telegraphing his last sentence for a hundred pages is too clever by half.

Conscious of sounding meanminded in all this, I should emphasise the very real positives in this tale of obsessive behaviour in the adolescent crowd. The portrait of tormented Jules is indeed subtle and complex. It sticks in the mind, and it is moving. The young woman desperate to absorb the strength of others who has not yet learned the strength in herself is rather more than a cliché here, and while the events are a shade too much like a straight-to-video exploitation movie to ring true, the personalities are not. Mr McFarlane really does know, I think, what young people are like. But his real triumph in this book is in the very brief sketch of Danny’s wife, alienated from the bush she loves because of the derangement enacted within it. That somehow hurts as much as anything that happened to Jules. Everything is not really returned to normal for her, for she feels compelled to move from her bushland eyrie to a commonplace suburban box. Her life will always be a little warped by it. Horror fiction for young people is invariably normative and restorative in the upshot, at least at the narrative level, but true horror cannot be exorcised by the reinstatement of the ordinary: there may always be that cold-eyed thing stirring in the cellar of the mind.

Comments powered by CComment