- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A New Justine?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Marilyn’s Almost Terminal New York Adventure offers all the ingredients that have made Justine Ettler’s name to date: sex, drugs, tough women, bad men, and rough prose. Thankfully it does leave behind some, though not all, of the relentless violence of The River Ophelia. Marilyn is not as hell-bent on the same masochistic path as Ettler’s earlier heroine, Justine, and the novel admits a lightness of tone which is initially refreshing.

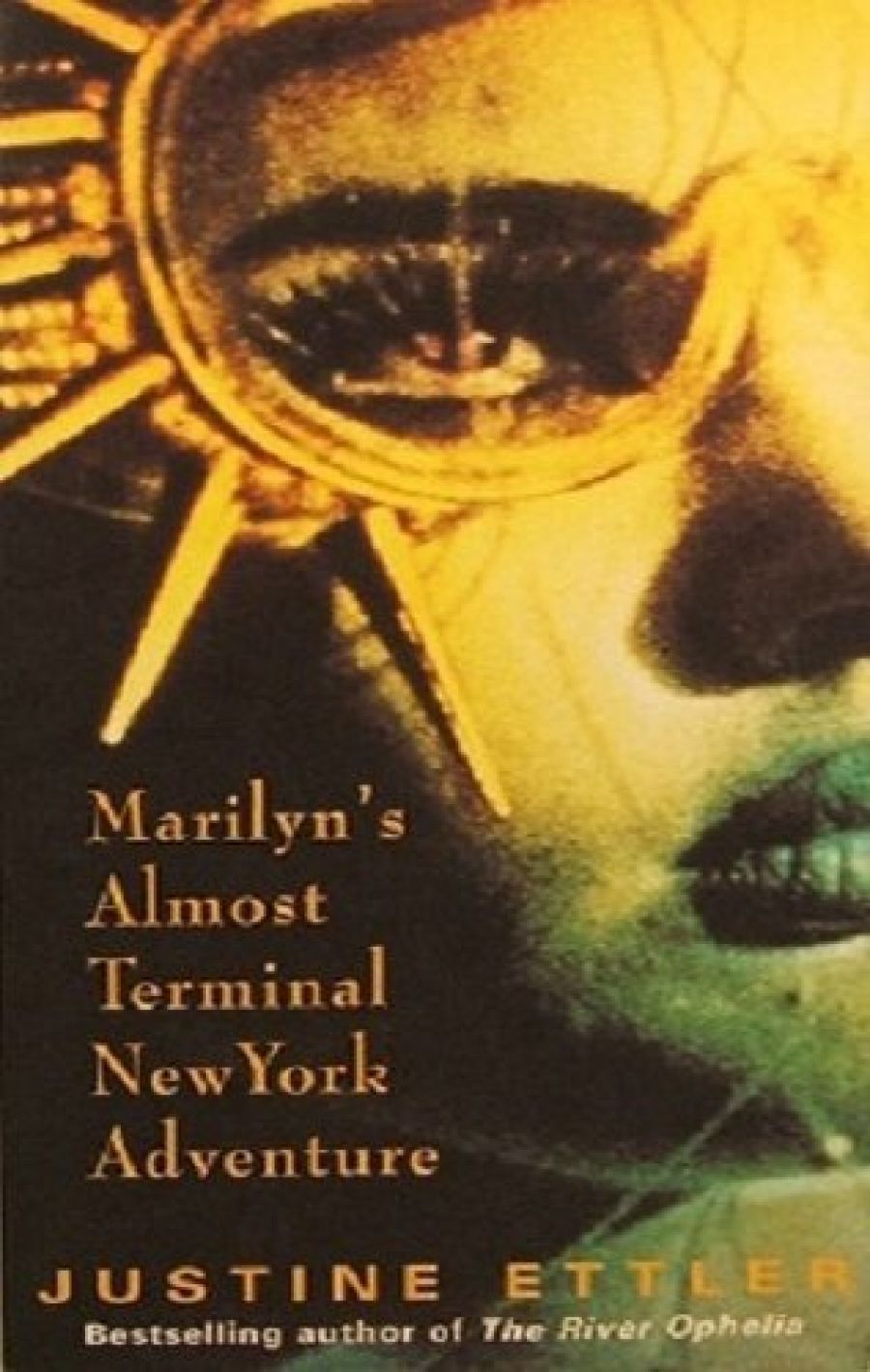

- Book 1 Title: Marilyn's Almost terminal New York Adventure

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $14.95, 254pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Instead it traces with a playful parodic voice Marilyn’s romantic quest half-way around the world to meet ‘Twentiethcentury Fox’ after seeing him on a matinee show. Marilyn is Superwoman, ‘very Marilyn with a touch of Meryl’, introducing herself as ‘musician journalist writer film-maker model research scientist’. She moves in a displaced literary coterie including ’Virginia deeply-enigmatic-ina-very-fames-Bond-girl-way Woolf’, Miller, Bronte, Lawrence, and Durrell. The narrative consists largely of Marilyn’s ‘remembrance of things past’ written as an extended ‘List of Names and Places’.

The novel dispenses at the outset with certain realist conventions. Ettler creates a dizzying whirl of stories as she intertwines Marilyn’s narrative with those of other characters, such as Bette the air hostess, who is suffering a case of Freudian surrender and perceives her life in terms of recovery from incest. Like Lawrence Durrell’s writer from The Alexandria Quartet, Ettler includes a synopsis of the adventure plot in a few lines at the novel’s opening. Durrell’s author/character does this so that he may set his book free ‘to dream’. In Marilyn’s Almost Terminal New York Adventure, however, dreams are more often melodramatic nightmares. In familiar Ettler style, Virginia slits her wrists, and Twentieth-century’ s silicon-breasted date repeatedly stabs a fork into Marilyn’s hand in revenge after she has emptied a plate of food down her back.

Such incidents suggest that, despite the comic tone and the change of setting from Darlinghurst to New York, the violent world of The River Ophelia is never far away. The atmosphere of Marilyn’s adventure, however, is freer and, with its tales of communal living, is slightly reminiscent of Helen Gamer’s Monkey Grip. Evicted from their house, Marilyn and Liz respond by partying with friends and, in this chaotic, carefree life, drugs become a form of communion, rather than simply another expression of the death drive.

Stylistically, Ettler’s work has less in common with the fiction of Helen Garner. The novel’s syntax becomes jerky and tiresome. The lack of punctuation and stream of consciousness narrative, which makes the 150-word sentence a commonplace, is achieved through a monotonous use of the conjunctive ‘and’.

Nominalised strings of description, such as ‘no-1-never-did-have-my-adenoidsout-so-yes-I-do-have-a-sinus-condition Twentieth-century Fox’, begin as humorous but soon become banal. Like the insistent references to literature and theory, such as Barthes’ ‘Death of the Author’ that hasn’t died, there is a certain point when the textual play starts to become irritating rather than witty.

Nonetheless Ettler delights in teasing her readers. Bette is the reader who wants desperately to know if Marilyn’s tale of sexual adventure with bananas is true or fictional, ‘because if it is true then it means I’ve led a very boring sheltered existence’. A similar desire to know fuelled the hype surrounding Ettler’s first novel. The River Ophelia played the game of the author who resists analysis. The Justine Ettler who was and was not Justine. Perhaps Ettler’s point is that, like Durrell’s Justine from The Alexandria Quartet, Marilyn and Justine each may be someone who

simply ... is; we have to put up with her, like original sin ... But to call her a nymphomaniac or to try and Freudianise her, my dear, takes away all her mythical substance-the only thing she really is. Like all amoral people she verges on the Goddess.

Whether either Justine or Marilyn could be called goddesses, though, is open to question.

Certainly, in this world of tough women there are no gods or Supermen. Grove instructs Virginia,’ Don’t envy balls Virginia, break them’. At the end of the novel, it is to the young female reader that Marilyn’s last words of advice are addressed:

Never neglect a girlfriend in your pursuit of a boyfriend because men are never as significant as they look and women are undisputedly more so.

With a little more of the Thelma and Louise touch she adds:

but most important of all never say no to adventures even when they threaten to become terminal because ... even if you end up feeling like the biggest loser in history you’ll still end up feeling like something.

Just in case the reader is caught up in the heroic sentimentality of Marilyn’s credo, Ettler has another narrative voice step in and explain that the idea is ‘mine’. ‘Yes’, the reader is told, this narrator is ‘upset’

about Marilyn’s tiny bit terminal state of mind when she suddenly evaporates from her chair and then passes straight into the television screen in a totally inconceivable didthat-really-happen? kind of way.

Is this disappointing ending a parodic play with the metafictional, postmodern, and all the techniques one is supposed to consider avant-garde? Or is it partly, as it is in danger of seeming, a writer’s desperate last resort when an ending refuses to appear in a flash of imagination, so the narrator wakes up to find it was all a dream? Or perhaps, some might claim, it’s just the reality of writing about virtual realities? If so, maybe sentimental realism was not so bad.

Though Ettler plays with the conventions of romance and realism in Marilyn’s Almost Terminal New York Adventure provide a lighter narrative than The River Ophelia, there is still a strong scent of the original Justine. Whether or not such tough prose will continue to be amidst Australia’s bestselling writing remains to be seen.

Comments powered by CComment