- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

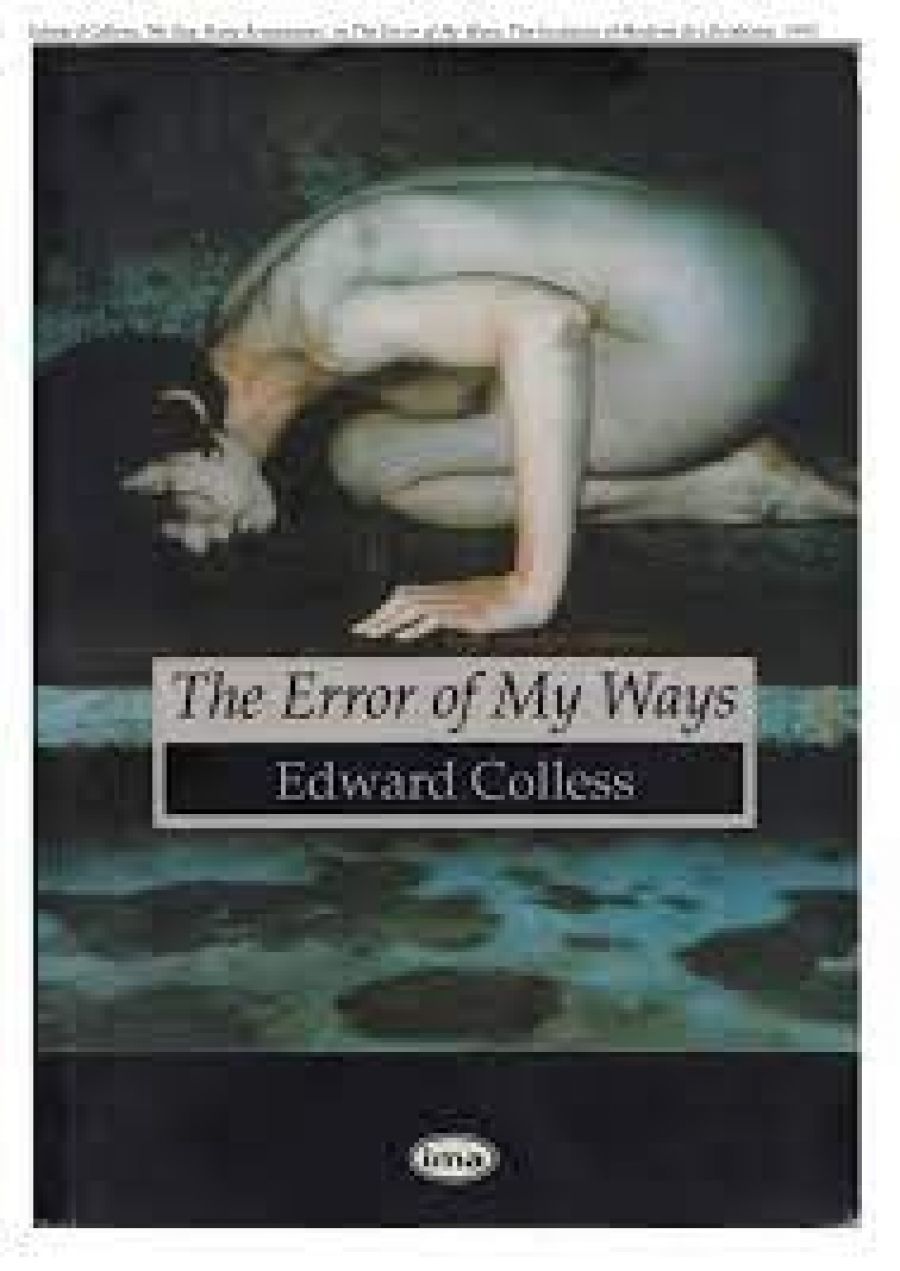

- Article Title: The Error of My Ways

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Edward Colless is the ‘don’ of the art world – in fact, he is Juan, Quixote, and Giovanni all woven together. The Error of My Ways is his ‘mille e tre’ of theoretical affairs – essays and articles that have infected an otherwise sterile art scene with a flame of desire.

- Book 1 Title: The Error of My Ways

- Book 1 Biblio: Institute of Modern Art Brisbane, $19.95 pb, 233 pp

The essays are divided into three sections: discursive essays (Folly’), occasional pieces (‘Lost World’) and artist commentaries (Two Evil Eyes’). Of the three sections, the first passes the test of time with highest marks, while the other two have definite archival value.

The contents of ‘Folly’ dwell on the nocturnal mysteries of consciousness. The title essay follows an intriguing line of thought that links a fascination with photographs of raised miniskirts to the uncanny history of faked UFOs which is concluded by a reflection on Anselm’s proof of God’s existence. The thoughtfulness of this journey from the ridiculous to the sublime is evidenced in the way he deals with the celebration of the flâneur in Benjamin and Baudelaire. It would be tempting to immediately recruit these names in support of his immediate subject, but Colless’ singular value lies in his capacity to keep a hold on authenticity. Sentences such as – ‘Yet it would embarrass these grand melancholic perceptions to have them strain as they squeeze into a shape appropriate to the sentiment in Tim Johnson’s photographs.’ – demonstrate his readiness to exploit the gap between the idea and its shadow.

These shadows are the subject of a more pugilistic response in his polemical pieces. The butt of Colless’ satire is the cult of high theory celebrated in Paddington cafés. His specific target is the ‘hypermannerist film theory’ which eschews a careful scrutiny of film content for interminable paradoxes, woven like cat’s cradles from abstract theories. He demeans the aim of this movement as an attempt to ‘decorate the empty notebooks of students like daily mottos or proverbs on the pages of a desk calendar.’ Colless persists in this attack with an almost sadistic relish as he puzzles ‘how young students found a correspondence between their manic, libidinal excursions into infernal nightclubs and their endurance of the sedative, fluorescent pallor of a seminar room’.

Given his introspective style, this change of register does suggest a struggle between the author and some interior demon of self-doubt. It is the possibility of self-incrimination which raises Colless’ attack above what otherwise might be just another smug gesture against ‘theoretical fashions’. Indeed, it drives the author to substantiate his argument by a systematic falsification of those positions and a careful demonstration of their blindness into artistic form.

Colless’ credibility as a critical witness is presented in the section titled ‘Two Evil Eyes’, which includes essays accompanying work by specific artists, many of them Tasmanian. The publication of essays without reproductions of the works that were their original subject threatens to narrow the audience to those ‘who were there at the time’. Their worth to the uninitiated lies more in the rich philosophical reflections used by Colless to frame the artist’s work.

This division between independent essays and site-specific responses makes The Error of My Ways a slightly imbalanced publication. The curious design decision to mark the margins with a dotted line seems to betray an unease at the more ephemeral material contained between the covers. Given the rare opportunity of a book publication in the visual arts, it seemed at first a wasted opportunity, as though a local crooner of untapped talent, when given the opportunity to perform in the concert hall, had persisted with his familiar clubland repertoire.

With reflection, I realised that this expectation was counter to the entire project of The Error of My Ways. Authors like Ted Colless are the moles of contemporary Australian thought. Avoiding conclusions, their project is to extent thought along rhizomic patterns – to explore detours. The result is a myriad of nooks and crannies in the form of paradoxes, uncanny coincidences and aporias. The danger in this enterprise is that it facilitates a ‘pizza by the metre’ mode of writing which is designed to accommodate the gallery’s printing budget. Its grace is a space within thought to append a sense of location made particularly elusive by our increased wordliness.

In his introduction, Rex Butler characterises Colless’ writing as an enactment of the ‘real’ in language, which he defines as ‘the constitutive inability of language to describe what it sees, to account for itself definitively’. The space evoked by this slippage between intention and expression is identified by Butler as ‘the realm of the body’. Butler is correct to seek something concrete as emerging from this gap, but if anything inscribes itself upon this space in The Error of My Ways it seems to be the genius of place.

The home for Colless’ thoughts – its framing moments – is recurrently Hobart:

These days, living in a region where the aurora australis often illuminates the lonely darker stretches of an evening sky, I might walk home from work beneath pale green flames licking upward in less than a second from the horizon of the stars over the city, or look southward across the mouth of the river at a burning mauve veil that shimmers and silently unfurls along the rim of the black ocean. These dim silent nights of both my boyhood and manhood grow cold with the apparitions of obscure magic.

In searching for a rubric to describe Colless’ tendencies, it is tempting to employ a concept like ‘gritty surrealism which evokes the phantasmagoria lurking in the shadows of life in a small town. The alternative concept of ‘Tasmanian grotesque’, which Colless has himself chosen to adopt from Jim Davidson’s Meanjin essay, seems a little too kitsch for the more testimonial manner of his writing.

Fellini once defined an artist as ‘A provincial who finds himself somewhere between a physical reality and a metaphysical one’. Like Kierkegaard in Copenhagen, Colless seems confined to Hobart – an exile that those of us on the mainland can only dream of.

Comments powered by CComment