- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Jolley Prize

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: One of the strongest markers of identity in my birthplace, Iceland, is the idea of independence. The country takes great pride in how it reacquired full independence from Denmark in 1944; one of the main political parties is called the Independence Party, and the most famous Icelandic novel is Independent People by Halldór Laxness ...

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Kári Gíslason reviews 'Henrik Ibsen: The man and the mask' by Ivo de Figueiredo, translated by Robert Ferguson

- Book 1 Title: Henrik Ibsen: The man and the mask

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $74.99 hb, 704 pp, 9780300208818

Such, in any case, was Ibsen’s self-conception, and one of the many strengths of this biography is that de Figueiredo does not deny its importance to the playwright. Clearly, seeing himself as an island state helped Ibsen, especially as his writing moved from early nationalist and historical plays to works like A Doll’s House (1879) and Ghosts (1881), which confronted audiences with their depictions of family life. But this biography also reveals how Ibsen’s representation of himself might be incomplete, and how it does not give us a full understanding of how he developed as a writer. The picture that emerges in this book is that Ibsen’s life and career were as much about connections and relationships as they were about independence and individuality.

The first of these relationships is expressed in the structure of the biography, which is organised according to the places where Ibsen lived. He was born in the small port town of Skien in Telemark, a fact that might once have been seen as remarkable, for why would such a talent as Ibsen’s emerge from provincial Norway? But de Figueiredo is careful to show that Ibsen did not necessarily have to fight the society around him in order to become an artist. Skien was, after all, a port connected to the wider world by trade, and the mid-nineteenth century of Ibsen’s youth saw a ‘peripheral cultural awakening’ in the whole of Scandinavia, not just in the capitals.

This is not to say that Ibsen did not possess a special talent – rather, that his talent and creative work emerged as part of changes in the society around him. As a boy, he made puppet shows that were admired, and his first friends recognised that he could write and were among his earliest advocates. Later on, and despite his acerbic manner, Ibsen made many friends and found loyal supporters. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson was a fellow writer and competitor, but also his friend and the godfather of Ibsen’s son, Sigurd. Bjørnson was often privately critical of Ibsen, but pressed his case publicly when Ibsen needed it. In Bergen and Freetown Christiania, Ibsen was valued and given theatre positions, jobs he claimed to dislike but which, on balance, were successful and gave him training in the practical aspects of theatre production. He often expressed hostility towards Norway, especially after its failure to support Denmark during the Second Schleswig War of 1864, and came to see himself as an exile living in a condition of ‘banishment’. But he also received regular stipends from the Norwegian parliament and he supported Sigurd’s return to their homeland.

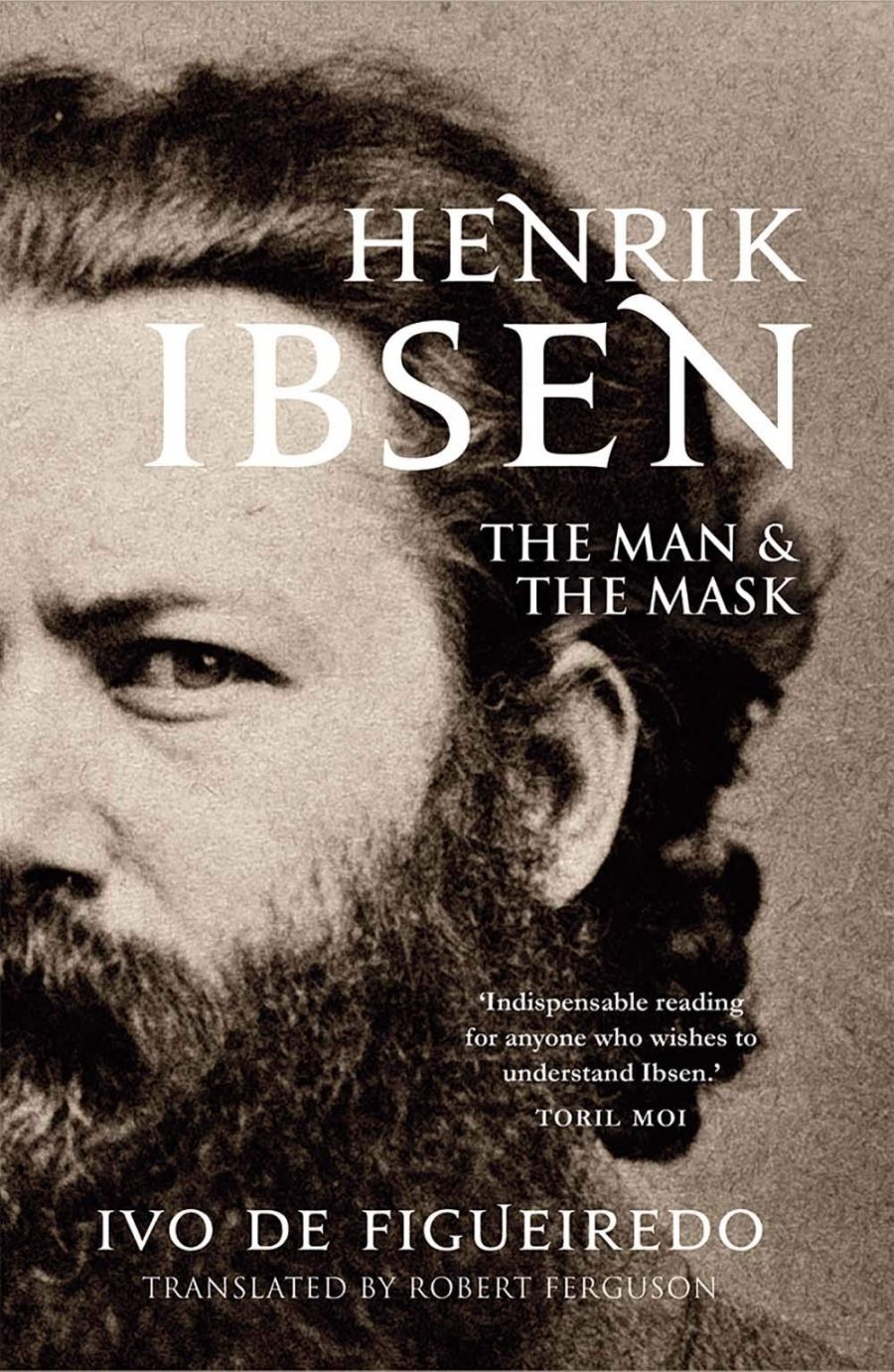

Henrik Ibsen (photograph by Gustav Borgen/Wikimedia Commons)

Henrik Ibsen (photograph by Gustav Borgen/Wikimedia Commons)

By highlighting such dualities, de Figueiredo’s study reveals that over the years readers and critics may have been a little too willing to accept a portrait of Ibsen that accorded with notions of the struggling, isolated artist. In this light, the story of how Ibsen’s father, Knud, fell on hard times and became bankrupt is presented as part of the commercial realities of the time. As well as looking at how Ibsen and the family were affected by their money troubles, we might consider how well Ibsen recovered in the period that followed, and how he still had opportunities for literary success. Similarly, his teenage years as an apothecary’s apprentice in Grimstad, sometimes seen as his ‘lost years’, did not prevent him from developing his writing. Instead, they offered him a period of artistic growth outside the more formal environment he would otherwise have encountered.

There is little doubt that Ibsen could be socially very awkward; he came to be known as ‘the most dogged individualist in literary history’. But this study of his life also reveals his ability to maintain relationships. He and his wife, Suzannah Daae Thoresen, were close, and he relied heavily upon her. Ibsen corresponded with his most influential critics, most famously Georg Brandes. He had a slightly distant but sustained relationship with his publisher Frederik V. Hegel, a leading publisher in Scandinavia. In other words, many people were willing to ride the bumps of his personality and his stated autonomy as an artist.

Most biographies of authors are also anatomies of authorship. In this work, we see a form of practice in which the author’s desire to stand outside the world was part of how he engaged with it. When he began to be received at royal and aristocratic courts, Ibsen compared himself with the travelling Icelandic skalds of the Viking Age; his place, he said, was ‘that of a skaldic poet at the foot of his prince’. If so, he was like the skalds in other respects, as well. They had a duty to tell things as they saw them: to do otherwise would be an insult to the king. By the standards of the day, they were quite free, for they could leave the king’s court. But this usually meant going to another court, and if not, then back to Iceland, where people were independent and also very connected and endlessly concerned with one another. We should be thankful that Ibsen’s version of the skald’s life involved a deep commitment to knowing and portraying others.

Comments powered by CComment