- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The inciting incident in Josephine Rowe’s short story ‘Glisk’ (winner of the 2016 Jolley Prize) unpacks in an instant. A dog emerges from the scrub and a ute veers into oncoming traffic. A sedan carrying a mother and two kids swerves into the safety barrier, corroded by the salt air, and disappears over a sandstone bluff ...

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Bronwyn Lea reviews 'Here Until August: Stories' by Josephine Rowe and 'This Taste for Silence: Stories' by Amanda O’Callaghan

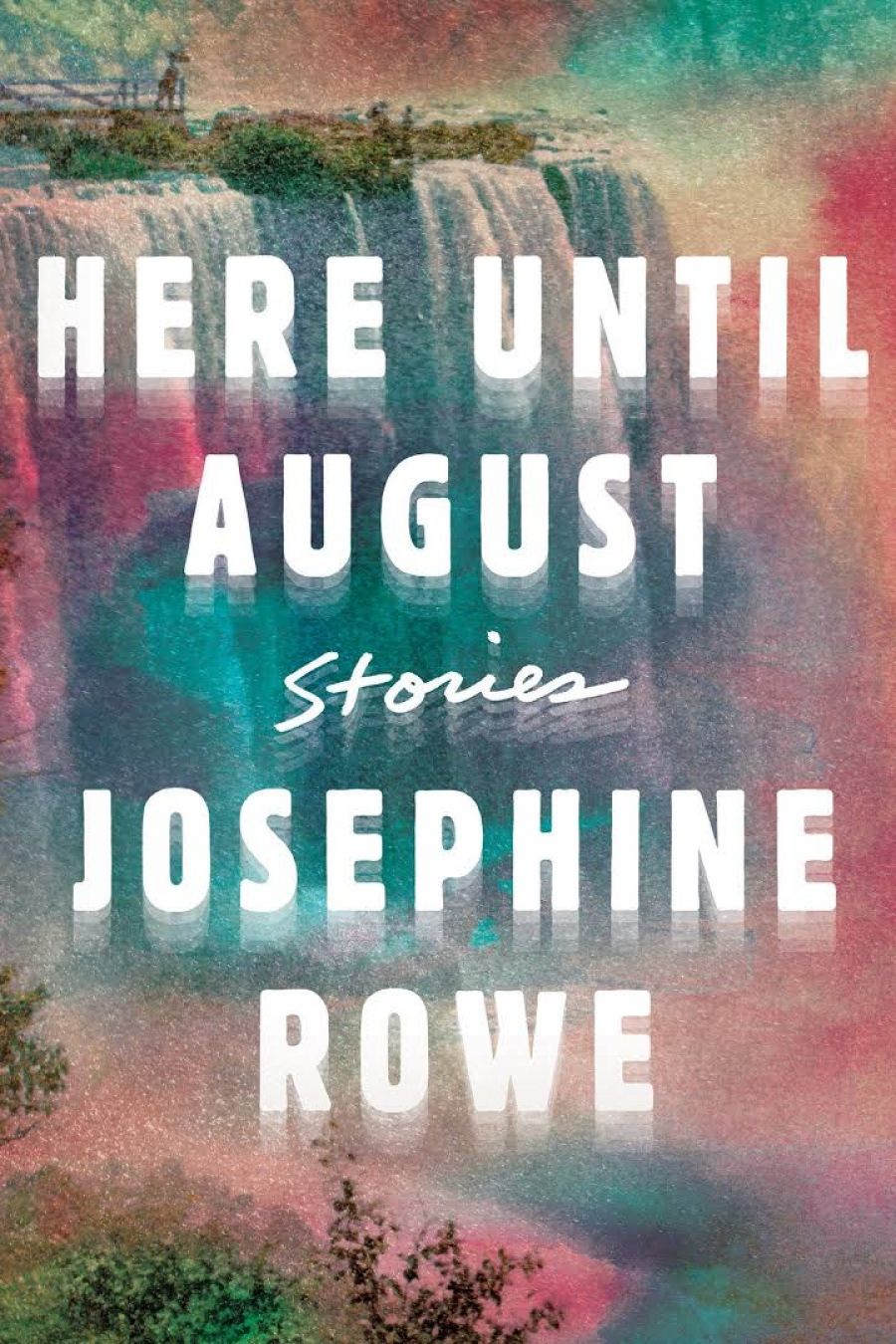

- Book 1 Title: Here Until August: Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.99 pb, 208 pp, 9781863959933

- Book 2 Title: This Taste for Silence: Stories

- Book 2 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.99 pb, 200 pp, 9780702260377

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Josephine Rowe (photograph by Derek Shapton)Here Until August ends in January, when it began, but having relocated to the northern hemisphere this time it is winter. In ‘What Passes for Fun’, a couple ‘somewhere close to the end of things’ drives past a frozen pond held aloft by the thin hollow stalks of a stand of cattails. Everything beneath the ice has drained away and the lake appears to levitate above a field. Later, at the in-law’s dinner table, the woman sets free a dangerous metaphor and watches it teeter across the table towards her husband. Still hopeful, he is waiting for something he can trust his weight on. But everything between them that was not solid has just drained away.

Josephine Rowe (photograph by Derek Shapton)Here Until August ends in January, when it began, but having relocated to the northern hemisphere this time it is winter. In ‘What Passes for Fun’, a couple ‘somewhere close to the end of things’ drives past a frozen pond held aloft by the thin hollow stalks of a stand of cattails. Everything beneath the ice has drained away and the lake appears to levitate above a field. Later, at the in-law’s dinner table, the woman sets free a dangerous metaphor and watches it teeter across the table towards her husband. Still hopeful, he is waiting for something he can trust his weight on. But everything between them that was not solid has just drained away.

Rowe’s first book, Tarcutta Wake, is composed of lyrical vignettes fuelled by poignancy and nostalgia. A Loving, Faithful Animal, a novel longlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award in 2017, lengthened Rowe’s narrative stride. Here Until August sees her return to the short story in full command of the form. ‘Glisk’ and the other nine stories that make up the collection are idiosyncratic, multifaceted, and exquisitely structured. Significance unfurls by stealth: absences accrete, insight pools in shadows, motivation refracts and misdirects, such that the characters that populate Rowe’s imagination arrive unprepared at their inevitable devastation.

Amanda O’Callaghan’s début collection, This Taste for Silence, is an assortment of twenty-one stories of varying lengths, from substantial narratives – such as ‘A Widow’s Snow’ or ‘The Painting’ that bookend the collection – to flash-fiction pieces of a few hundred words. Whereas Rowe, a guardian of idiosyncrasy, grants her characters nomadic lives and climactic interiorities, O’Callaghan’s satirical eye is drawn to characters – usually older women living predictable lives – who prefer generalities over particulars, timid souls who ask for little and deliver less. Hemmed in by convention and ridden with fear, their lives collide, at O’Callaghan’s dark bidding, with a human menace that moves all around them and within.

‘A Widow’s Snow,’ a black comedy of sorts, proves the maxim that late-life dating is not for sissies. Married for forty-six years, Maureen is newly widowed and hopeful that love might bloom twice in her lifetime. She settles on Roger, an antique dealer from South Africa. He is ‘the kind of man who would appreciate an old-fashioned pudding’ and she is the kind of woman who would cook it for him. Lacking introspection, Maureen projects her sense of self onto her home and its furnishings: she regards her clotted-cream walls, the watery-green plates stacked on an open shelf and wonders how someone, ‘seeing this kitchen, this house’, might describe its owner. Predictably, the dinner is a disaster: Roger is a bore and quite possibly a psychopath. The night ends with the pair both snowbound, Maureen locked alone in her bedroom, watching the snow-lit square of window and waiting for morning.

Silence comes in many forms – deceptions, departures, deletions – but, for O’Callaghan, silence typically takes the shape of death. In ‘The Golden Hour’, a woman spends the ‘sixty precious minutes’ after her husband’s heart attack walking around her house. The little clock her grandmother gave her chimes each fifteen-minute interval with a single fairy-bell note. Her husband is on the bathroom floor, eyes open, underpants tangled round his feet. After the third chime she picks up the phone and calls an ambulance. ‘Come quickly,’ she urges.

The half dozen or so flash-fiction pieces that punctuate A Taste for Silence hover in the liminal space somewhere between poem and short story. Chiefly portraits, they reveal O’Callaghan’s more tender side, trading humour and narrative for resonance and deep image. In ‘Tying the Boats’, a migrant bride cuts her long hair a week after her wedding and stores the hank, bound in red ribbon, in an old oak drawer. Years later, she retrieves the fading relic and weighs it in her hands: it is ‘thick, substantial, heavy as the ropes they’d used when she was a girl, tying the boats when storms were coming’. Likewise, ‘The Way It Sounds’ makes a study of how significant events continue to haunt long after they have ended. Uncle Hector is a returned soldier with a hole in his neck from where he was shot. The children like to plug their fingers into the little trench at the back of his head. One day someone asks him where the bullet went. Uncle Hector rubs his hands together as if he were cold: ‘Straight into the head of my mate.’ Later, the kids listen to Hector digging in the backyard for hours and for no good reason. His shovel makes ‘the sound of metal, hitting hard.’

Comments powered by CComment