- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Unlike an autobiography, which tends to be time-bound and inclusive, the memoir can wander at will in the writer’s past, searching out and shaping an idea of self. Although Geoffrey Blainey’s memoir, Before I Forget, is restricted to the first forty years of his life, its skilfully chosen episodes suggest much more ...

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Before I Forget

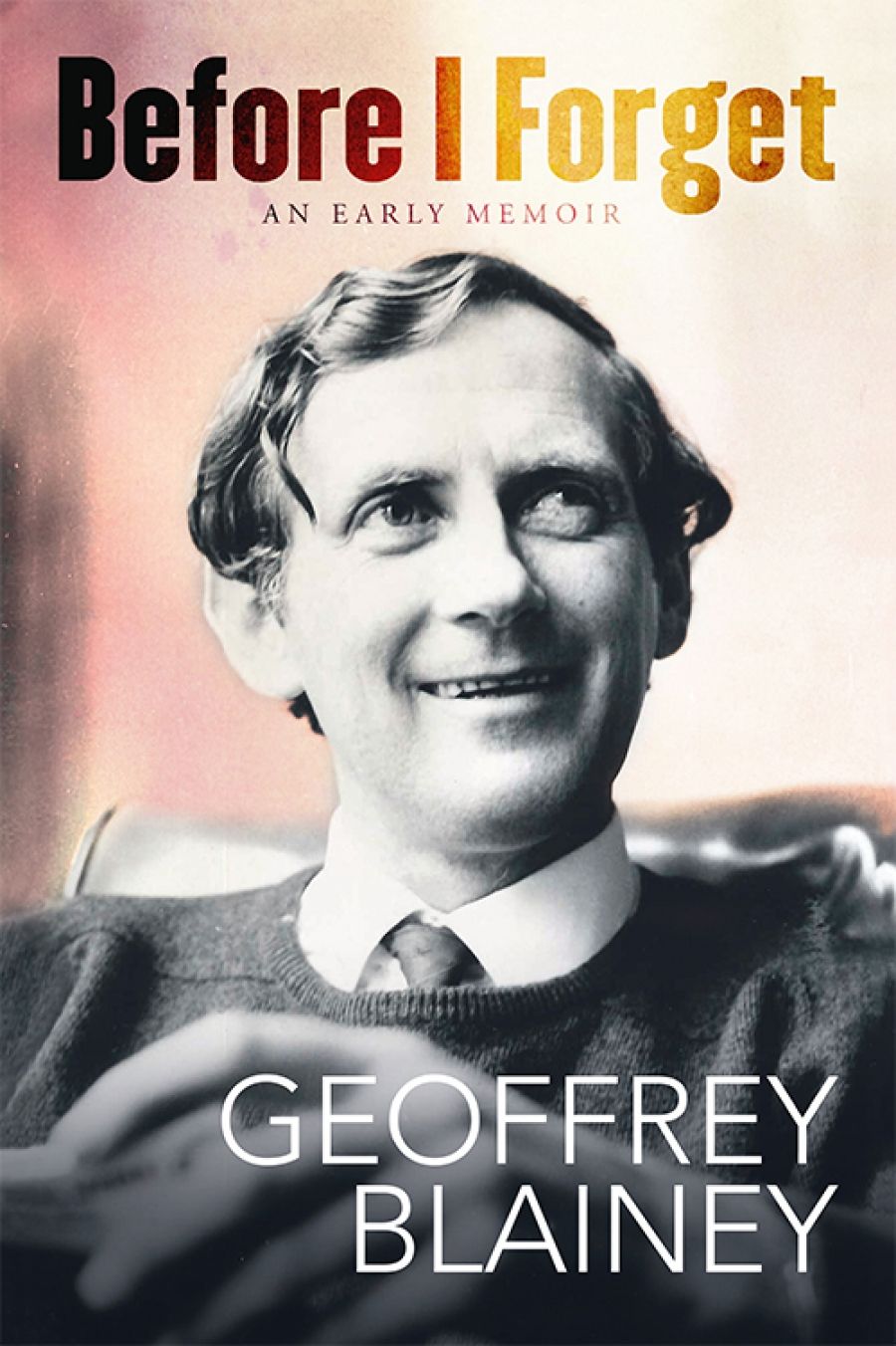

- Book 1 Title: Before I Forget: An early memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $45 hb, 340 pp, 9781760890339

Another clergyman’s son, historian Manning Clark, claimed (with some self-dramatisation) to have been tormented and patronised at Melbourne Grammar School. Blainey has no complaints about being a ‘scholarship boy’ at Wesley. He counts himself lucky to have been taught English by writer and critic A.A. Phillips, who was forthright about ‘flabby’ or ornate prose. Blainey was not quite seventeen when he entered the University of Melbourne, with a senior government scholarship and a free place at Queen’s College.

Blainey writes warmly about his time as a history student, the kindness of his tutor Manning Clark, and the charm of Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s incomparable lecturing style. Editing the student weekly Farrago gave him a whiff of the exciting world of print. His co-editor, law student Tony Harold, a Catholic and ALP member, was deeply and publicly committed to abolishing the White Australia policy. Blainey valued social cohesion over diversity. Although he was a wholehearted follower of Prime Minister Robert Menzies, he admired the opposition leader, Arthur Calwell, who had rigidly administered the White Australia policy during his term as Labor’s immigration minister. In 1950 the two Farrago editors took it in turns to bring out a paper that differed in style and tone from week to week. ‘We didn’t argue or quarrel,’ Blainey recalls. They just got on with it, on parallel lines.

Geoffrey Blainey (photograph via Black Inc.)Blainey completed his arts degree with first-class honours, as expected. But when it was time to take his place in the academic procession, he opted out. Later, he refused the formality of accepting his Master of Arts degree. It is hard to understand his motives, or to reconcile them with the calm and amiable young man who had moved so easily through his university course. Did he suddenly rebel against doffing his hat to the vice-chancellor? Was it because everybody walked in procession together, wearing the same robes? Could this be an early showing of the contrarian historian Blainey was to become? His own explanation is that the graduation fee felt like a tax on knowledge. He had no known personal grievances; the university system had treated him well. The refusal to take out his degree appears as the only wayward gesture of his student days. Years later, when Blainey was appointed to the Australian Studies chair at Harvard, the anomaly of a professor with no degree was resolved by David Derham, the vice-chancellor, who had the two degrees conferred in absentia.

Geoffrey Blainey (photograph via Black Inc.)Blainey completed his arts degree with first-class honours, as expected. But when it was time to take his place in the academic procession, he opted out. Later, he refused the formality of accepting his Master of Arts degree. It is hard to understand his motives, or to reconcile them with the calm and amiable young man who had moved so easily through his university course. Did he suddenly rebel against doffing his hat to the vice-chancellor? Was it because everybody walked in procession together, wearing the same robes? Could this be an early showing of the contrarian historian Blainey was to become? His own explanation is that the graduation fee felt like a tax on knowledge. He had no known personal grievances; the university system had treated him well. The refusal to take out his degree appears as the only wayward gesture of his student days. Years later, when Blainey was appointed to the Australian Studies chair at Harvard, the anomaly of a professor with no degree was resolved by David Derham, the vice-chancellor, who had the two degrees conferred in absentia.

If Blainey had embarked on an academic career in 1951, it would have meant a few years as a tutor, followed by an overseas scholarship to study at Oxford or Cambridge. That was never what he wanted. More ambitious and more of a risk-taker than most, he planned to write history, not to teach it. He was helped on this adventurous path by Max Crawford, head of the history department, who recommended him to the board of the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company, then in search of an historian. The Peaks of Lyell, published by Melbourne University Press in 1954, was the first in a series of commissioned histories, written with flair and judgement, from which Blainey made a precarious living for some years before taking an academic post. Bestsellers followed. Ideas tumbled out in generous profusion. The Rush that Never Ended (1963) and The Tyranny of Distance (1966) were reprinted many times. Well before his fortieth birthday, Blainey had found a wide general readership.

Blainey’s habitual nostalgia appeared in Black Kettle and Full Moon: Daily life in a vanished Australia (2003).He writes with the same affection in Before I Forget about his mother’s household work. Coming home from school, he would find her baking cakes, making jam, bottling fruit, darning socks. She had no refrigerator, no electric or gas stove, no vacuum cleaner. The values embodied in these memories sustained the historian in later years, but did not rule out a lively curiosity about the changes the future might bring.

Before I Forget conveys the romantic excitement the young Blainey felt in discovering primary sources. Old letters, even columns of figures, were brought to life in the Mount Lyell project. Blainey learned how to make ‘a mosaic of tiny facts culled or scrounged from everywhere’. The Mount Lyell chapter shows the awakening of the young writer, alone in the Tasmanian wilderness. The ghostly remnants of the old copper mine near Zeehan brought him close to the past. For the way they faced danger and solitude, miners became his heroes. They still are. In the present context, this may seem unhelpful. But, take it or leave it, that’s Geoffrey Blainey.

Comments powered by CComment