- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian journalist and author David Leser’s 2018 Good Weekend article, ‘Women, Men and the Whole Damn Thing’, sparked a wildfire of commentary, confession, and praise. Written in the early white heat of the #MeToo movement, the Harvey Weinstein exposé, and Oprah Winfrey’s 2018 Golden Globes speech in which she spoke out on behalf of the Time’s Up campaign ...

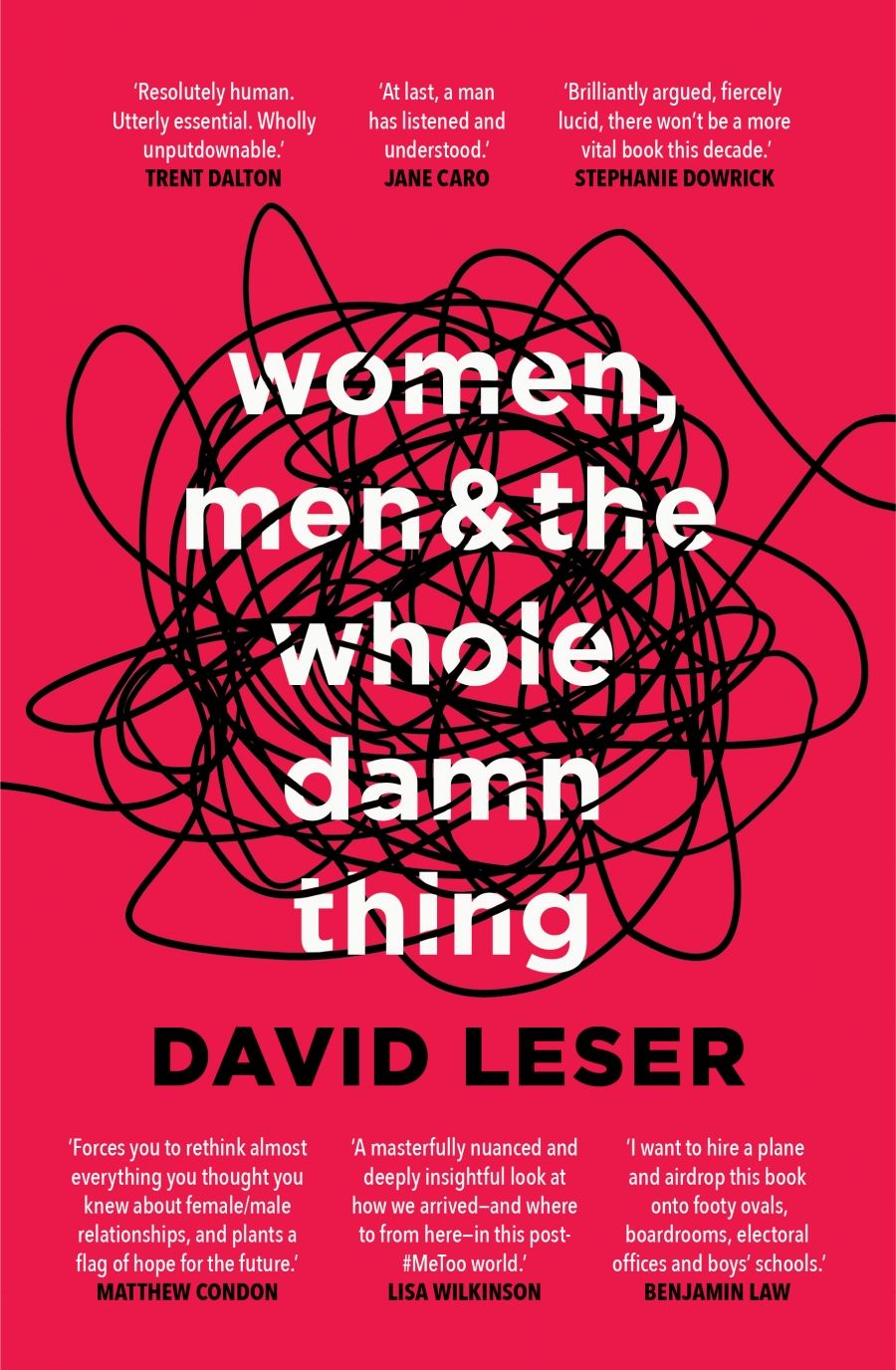

- Book 1 Title: Women, Men and the Whole Damn Thing

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 336 pp, 9781925266108

A daunting task. So fast-moving are events that a number of high-profile legal cases – including those of Australian actors Geoffrey Rush and Craig McLachlan – are presented as being up to date ‘at the time of writing’. And sadly, there’s no shortage of up-to-the-minute material for Leser to choose from. Statistics, testimonies, and anecdotes combine in this hair-raising, frequently stomach-churning compendium of violence against women, and men’s role in perpetuating that violence. Flitting between the personal and global, Leser argues compellingly that misogyny in its multifaceted modern form is inherited from the world’s main religions, that the dubious privileges of masculinist culture are there for the atheist and pious alike, and that those of us who notice them least are those they serve the best.

A recurring opinion – articulated most devastatingly by Eve Ensler, campaigner and author of The Vagina Monologues – is that men have long been policed, by others and themselves, to ‘cage and kill the feminine within their own beings and consequently the world’ – a deeply ingrained trait that makes crying unthinkable and ultimately, in Leser’s words, ‘obliterates women and girls’, as well as ‘weaker men, more feminine men, gay men, different men, transgender men and, of course, children in all their divine innocence’.

With Zainab Salbi – author, broadcaster, and founder of Women for Women International – he discusses the allegations published in 2018 on Babe.net against stand-up comedian and actor Aziz Ansari by a young woman, dubbed ‘Grace’, whose romantic date with the star, described in some detail, ended with her being ‘taken advantage of’. The backlash against Ansari, a self-proclaimed feminist, was swift, as was the counter-reaction against Grace, who was pilloried on air by the Canadian–American broadcaster Ashleigh Banfield for having potentially destroyed Ansari’s career on the back of ‘a bad date’. Because of the ambiguities it touches on, Salbi believes this story is, in many ways, more important than the transgressions of the Harvey Weinsteins of this world. When it comes to what most women actually go through, she tells Leser, ‘80% of the story is the Aziz Ansari case’.

Helen Garner, a friend of Leser, had a ‘squirmy feeling’ when reading the Ansari story, and says she’s primed to detect a ‘whiny’ note of entitlement in the political position taken by certain – invariably younger – women: ‘It’s like someone with road rage: anyone bumps into them and they go berko …’

Leser’s twenty-four-year-old daughter, Hannah, is incensed by Garner’s comments; his twenty-nine-year-old daughter, Jordan, views the Ansari story as a ‘disgusting one-night stand’ but not sexual assault. Which is to say, there is generational and geographical dissonance as to which male behaviours merit private redress and which ones – if any – warrant a potentially ruinous trial by social media.

That lack of consensus extends to consent and what it should look like in practice. There is now an app – uConsent – that generates a ‘consent barcode’ digitally stored when willing sexual parties agree. And then there’s what is for me, personally – a straight white man with two young boys who still cry freely and clutch teddies – a more promising initiative. Leslee Udwin, following her documentary India’s Daughter about the gang rape, torture, and murder of medical student Jyoti Singh in Delhi in 2012, founded Think Equal, a widely piloted school program to teach children aged three to six skills such as empathy and self-regulation, ‘so that they don’t grow up to rape, bully, become addicted to substances or commit suicide’. Get them young, in other words, to start countering the brutal exceptions and universal pressures of masculinity.

This is an important book, heralding and contributing to what, with luck, will become a workable roadmap beyond patriarchy. I would challenge anyone to read it without pangs of recognition and/or self-recognition. It’s a testament to the strength of Leser’s thesis that the inevitable conclusion seems at once counter-intuitive, simplistic, and profound: for everyone’s good, men – all men – need to find ways to start loving and respecting themselves.

Comments powered by CComment