- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the 1970s, before Malcolm Fraser (ahead of his time) tightened security and made most of the place a no-go zone, Australia House – a regular embassy – also functioned as an informal social amenity for visiting Australians. There was a howling disjunction between ...

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Capital Designs

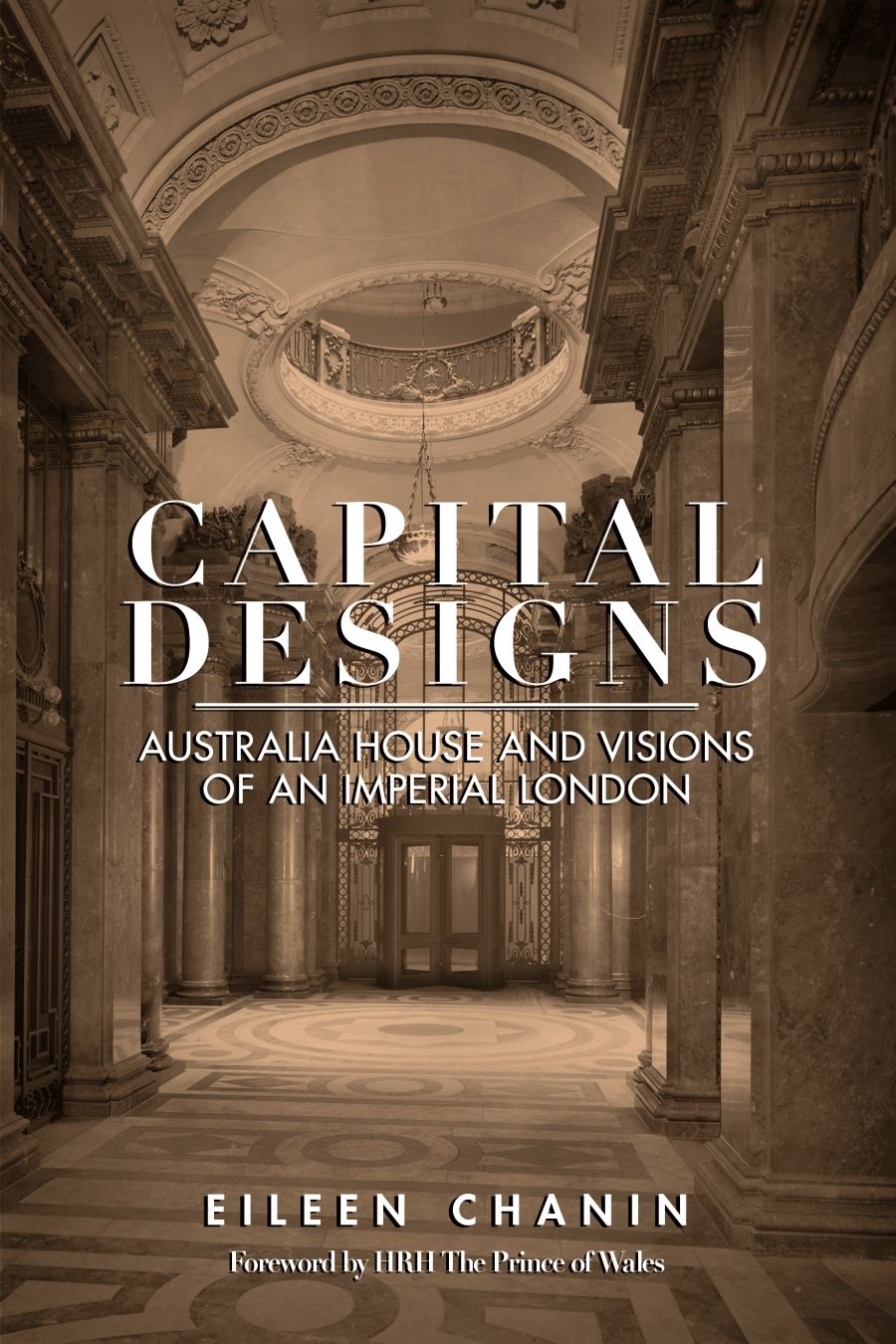

- Book 1 Title: Capital Designs

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia House and visions of an imperial London

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Scholarly Publishing, $49.95 pb, 436 pp, 9781925801316

Chanin sites the building of Australia House within the context of the reimagining of London as an imperial capital: the development of The Mall as a processional street, and in particular the creation of Kingsway, where all the buildings were to be faced in stone. Development there was tardy: the construction of Australia House nearby gave it a much-needed boost and also acted as a spur to other British Dominions to build comparable establishments. Moreover – beyond the bounds of this book – the imperial vision, expressed in stone, extended to the inauguration of New Delhi, the Union Buildings in Pretoria, and even, in a minor key, to Canberra. The style chosen here would be the French Beaux-Arts, with its classical colonnades and aspirations to timelessness (suggesting imperial permanence). The result was a massive monumentalism. The convict colony had arrived.

The Australia House site was a strategic one, halfway between the financiers of the City and the politicians at Westminster. The newspapers of Fleet Street were just down the road, while Australia House fronted on to London’s most frequented street, the Strand. That was important for attracting immigrants; Australia was lagging badly behind Canada. People would also be drawn to the various exhibitions planned for the ground floor hall.

For a long time nothing happened. While various schemes swirled about after slum clearance, wildflowers grew on the site. The respective agents-general carried on the business of each state as if the Commonwealth did not exist. Meanwhile, the London City Council resisted selling the freehold, although the Victorian government was able to secure part of the site to build Victoria House. The architect did draw up plans for an Australian building covering the whole corner site, but there was no progress. Nonetheless, the idea of the proposed building enjoyed wide support in Australia.

Victory March on 3 May 1919 around Australia House on Strand in central London (photograph via ANU)

Victory March on 3 May 1919 around Australia House on Strand in central London (photograph via ANU)

The deal eventually concluded, ideas of a competition or of having an Australian architect were soon discarded: the Scot Alexander Marshall Mackenzie was chosen (in partnership with his father). This led to a greater insistence on Australian materials being used in the building, wherever possible. While Australia House would have the new steel frames and other innovations, in appearance it would be traditional. Marble, stone, and timber would be required – and all of these would be sent across the seas from Australia.

Building was slow. There were stoppages and, once the war began, long interruptions in the supply of materials: ten tons of Victorian marble had to be shipped to London every fortnight. Unforeseen difficulties included a standoff between the sculptor of the pieces that were to flank the entrance and Mackenzie, who insisted that they should harmonise with the building. Australia House was slow to advance beyond the three jagged storeys that were in place when the war began in 1914.

There were broader problems. Victoria House had been integrated with the new building; New South Wales wanted matching quarters on the east side. None of the other agents-general moved in, as had been hoped. Meanwhile, it had become plain that Australia House would cost nearly ten times as much as the new Commonwealth offices in Melbourne; people began talking of the ‘white elephant’ on the Strand. The high commissioner soon found it expedient to move into the building when it was far from finished. It was not even complete when the king inaugurated it, nine years after Victoria House was open for business. The muted wartime opening nonetheless brought accolades – not least from Queen Mary, who thought the building ‘Very fine inside, marble & wood from Australia, very good taste’.

The scholarship evident in this book is daunting; the text is sometimes discursive. But Capital Designs is moved along by some fine passages. There are deft portraits of advocates for Australia House such as King O’Malley, while George Reid, usually regarded as a slob, is here presented as urbane, quick on his feet, and good at getting things done. Chanin is skilful in analysing architecture, explicating sculpture, and atmospheric in describing the great occasions.

Understandably, Chanin tries hard to argue for the building, but concedes it is grandiose. That was the point: it was deposited by the high tide of Edwardian imperialism. It is not pathetic like Perth’s London Court, a mock-Tudor tribute to Olde England. Nor is it in the style of Melbourne’s GPO, which, now it has lost its function, stands out more clearly as an artefact of Empire. Indeed, the building could almost be said to have the last laugh. Australia House is now the longest continually occupied foreign legation in London.

Comments powered by CComment