- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Shakespeare

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ben Jonson famously derided Shakespeare’s grasp of ‘small Latin and less Greek’, and vocal sceptics in our own time refuse to believe that a grammar-school education was sufficient to enable the man from Stratford to write the plays attributed to ‘Shakespeare’ ...

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): How the Classic's Made Shakespeare

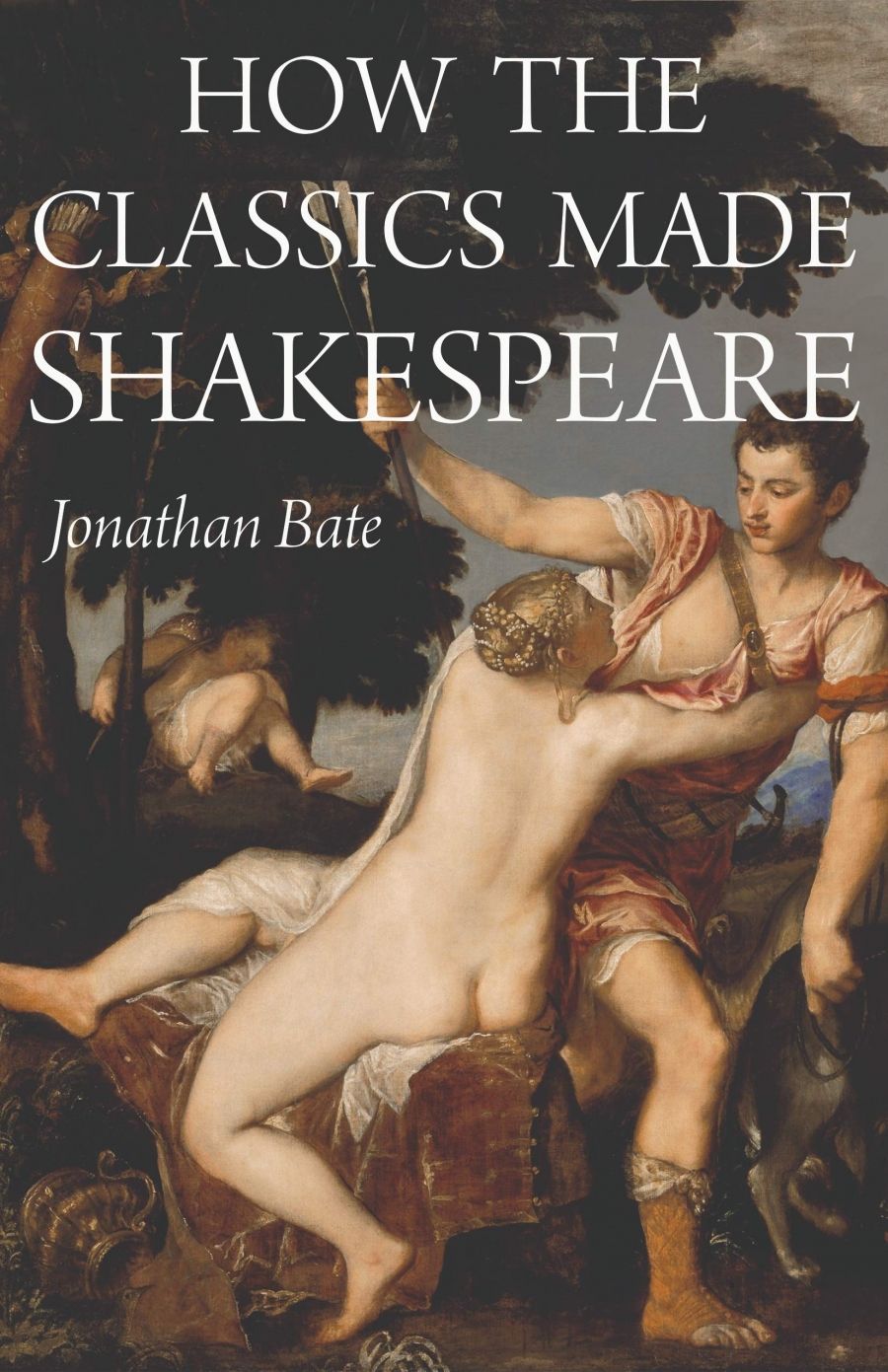

- Book 1 Title: How the Classics Made Shakespeare

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint), $49.99 hb, 361 pp, 9780691161600

Bate situates Shakespeare’s work as ‘part of a national project to invent a new cultural heritage on the model of ancient Rome’ (including through resistance to modern Catholic Rome). This model of ‘succession through resistance’, he notes, is evident through the nomenclature and architecture of Shakespeare’s London, was commented upon by travellers of the time, and featured in the education of the grammar schools – in short, it so completely engulfed the young William Shakespeare that it is no surprise his works owe a substantial but remarkably diverse debt to the classics. In one chapter, Bate uses the example of a Latin epigraph, one referencing Jason and the Argonauts on a monument in Shakespeare’s parish church in Bishopsgate, as the entry point for discussing how Shakespeare’s England maintained a meaningful cultural connection to Ancient Rome despite Henry VIII’s breaking with the church. Elsewhere, he examines how Cicero’s concept of ‘civil war’ (made famous by Julius Caesar) coloured Shakespeare’s conception of the Wars of the Roses, and how the translatio imperii trope that imagined London (Troy Novant) as the reincarnation of Troy and Rome affected a Londoner’s perception of their place in the world.

The creation of the English nation-state in the sixteenth century required ‘a distinctively national body of English tradition’ that was nevertheless ‘built on the classical tradition’. While the role of grammar schools and educational advances in the creation of this national culture were important, it is by overwriting or exceeding the ancients that Shakespeare helped establish a national, vernacular literature for England. How the Classics Made Shakespeare is thus also a study of ‘Shakespeare’s quick-witted and fast-paced reanimation of the powers of the classical imagination’; how Shakespeare brought the ancient world ‘into the presence’ of his audiences and readers.

Portrait of Shakespeare from the First Folio (1623), copper engraving by Martin Droeshout (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Shakespeare from the First Folio (1623), copper engraving by Martin Droeshout (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Within the book there is still scope to attend to specific classical texts that influenced the young Shakespeare. Bate explores Shakespeare’s schooling and immersion in the classics from an early age; how his imagination was fired by the ‘deliberative technique’ he acquired through rhetoric classes, and how the classical ‘uses of history, of illustrative parallel, of tale and fable’ had a formative effect on the young writer’s creative powers. He notes that it was classical works, including Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, that led Shakespeare to ponder the big questions in politics: ‘monarchy versus republicanism versus empire; the choices we make and their tragic consequences; the conflict between public duty and private desire’. Cicero, Horace, Ovid, Seneca, Tacitus, and Virgil in particular receive this kind of attention in Bate’s study, but, as he describes it, his argument has a broader, dual purpose: it encompasses ‘Shakespeare and the classical tradition’ and ‘Shakespeare becoming the classical tradition’ for subsequent generations.

With that declaration of the study’s relevance to the present comes an attendant sense of urgency for Bate’s book, written at a time when the classical tradition ‘is in danger of burial beneath the avalanche of the information revolution, and where its spirit of dialogue between different languages and cultures is ebbing rapidly away’. A study such as this is needed now precisely because there is a risk of ‘the long view of the past’ becoming ‘flattened by the simultaneity of data derived from the digital world’. Modes of thinking are changing, familiarity with the classics cannot be taken for granted, and Bate exploits the curious vantagepoint available whereby an analysis of a culture saturated with the classics can be offered from the perspective of a culture that is potentially drifting away from them.

Comments powered by CComment