- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

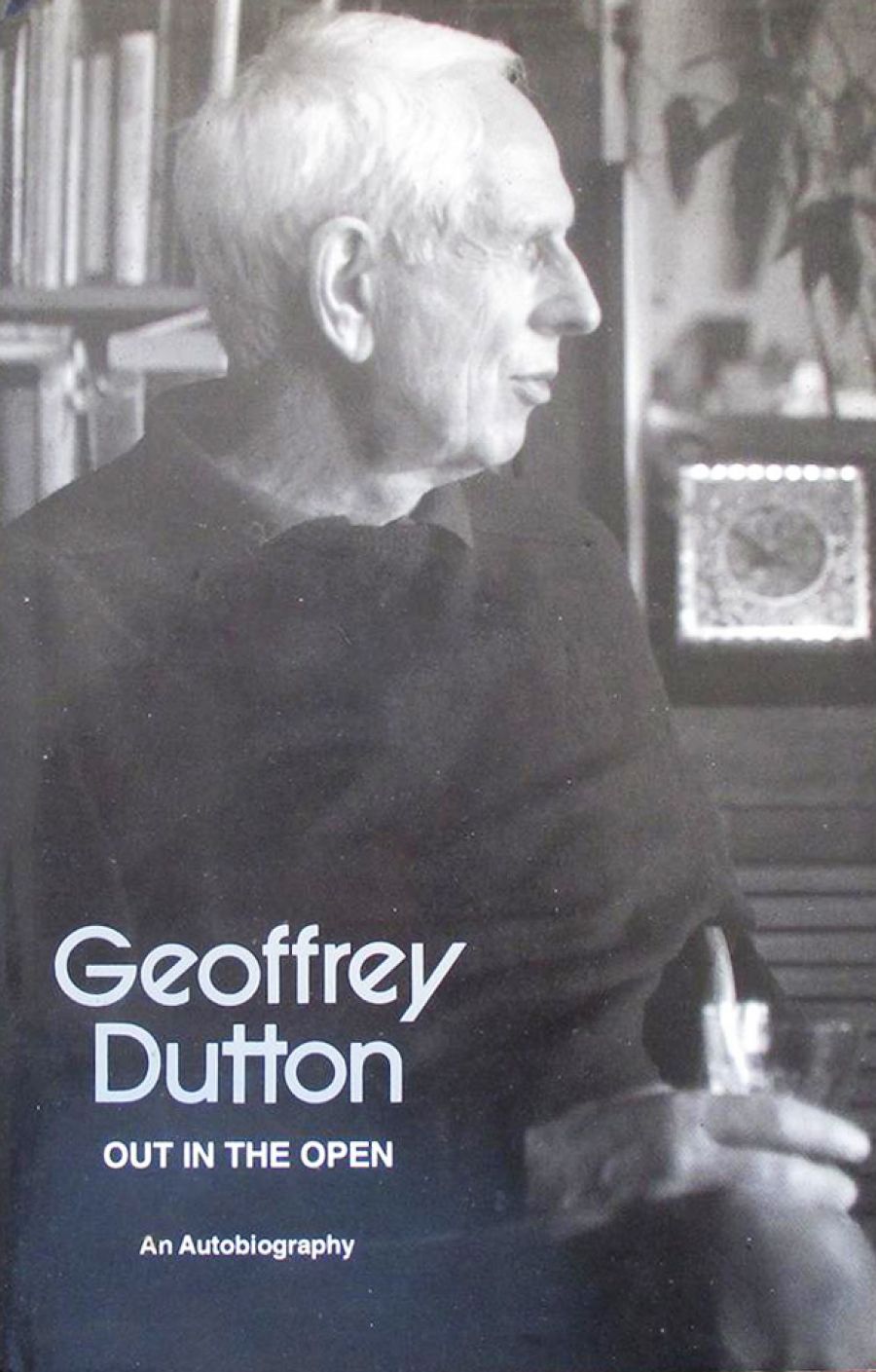

Literary biographies are reputedly more widely read than their subjects’ own works: more people have probably read David Marr’s biography of Patrick White than have tackled The Twyborn Affair or The Aunt’s Story. The same may perhaps can be said for autobiography, and it’s my bet that Geoffrey Dutton’s Out in the Open will attract more attention than, say, his novel, Andy (Flying Low), his collections of poetry, or even his impressive biography of Edward John Eyre.

- Book 1 Title: Out in the Open

- Book 1 Subtitle: An autobiography

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, S39.95 hb

There is much in Out in the Open that is of interest, especially for those who are curious about Australian literature and the history of publishing in this country. Literary gossip abounds. Nostalgia is subverted and marital infidelities are justified. The book will probably cause controversy – Dutton has not been a publisher for nothing, he understands marketability very well. Some academics may take exception to the assertion that ‘literary theory and its deadly jargon sprays over critical writing nowadays like acid rain’, while others will undoubtedly concur.

People write autobiography for different reasons. To put the record straight by telling it their way. To examine their lives, suffering readers the chance to share a mind at work, or to understand the nature of suffering. Geoffrey Dutton chooses another way, presenting his life through a series of events, including notable encounters (often with the rich and famous) and difficult confrontations. The text glitters with the names of well-known writers and artists (almost exclusively men) who were also his friends – Patrick White, Sidney Nolan, Max Harris, Robert Hughes, Barry Humphries, Russell Drysdale, Yevtushenko, and Alistair Kershaw, to name a few. He also tells us international travel, good food, fine wine, attractive women and fast cars; of holidays at Rocky Point, Kangaroo Island, with family and friends. His literary achievements are significant, as a publisher as much as a writer.

Why then did I feel disappointed – as though I’d eaten well, but was still unsatisfied? Perhaps it was because Dutton is not given to introspection; there is little examination of an inner life. The quote from Henry James, which appears on page 254, may offer a clue to this reluctance to probe: ‘I daily pray ... to be suffered to aim at superficial pleasure.’ Angst is not something Dutton indulges in.

The book moves chronologically through seven stages (ages?) and while he may well have crept unwillingly to school, the ageing Dutton is far from sans teeth (or sans anything else that matters).

Born in 1922 to what can only be seen as a privileged Adelaide family where ‘some things were never talked about’ (something he does his best to reverse, as his title suggests), Dutton explains that the family wealth was more or less dissipated by the time he was a schoolboy. His parents continued to live in style, his mother travelling widely and being presented at Court while the children were given what might be perceived as a traditional English upbringing which included boarding school. This, for Dutton, meant the prestigious Geelong Grammar, about which he had mixed feelings. He does his best to dispel the myth of privilege, but not convincingly, I felt – even a second-hand Rolls Royce doesn’t come cheaply.

It was hard work to maintain the lifestyle to which he had become accustomed and which is out of the reach of most Australians. To do so meant seizing every opportunity: writing and editing commissions, lecturing, contracts, invitations for residencies (often through useful connections) in Australia and overseas, and as literary advisor. As a result, he seems to have been here, there and everywhere; as poet, historian, publisher, editor, member of various boards, as well as busy with the intricacies of his private life. Patrick White warned him he was spreading himself too thin, but, in Dutton’s own words, ‘I have always been unable not to have a go at whatever seemed worth doing; perhaps it’s an indication of shallowness of mind.’

‘Wartime 1941-45’ recaptures something of the euphoria of youth as well as the danger and challenge associated with war. No Wilfred Owen here. Instead, these young flyers lived for the moment, engaging in some dangerous pranks, one of which resulted in a death and earned Dutton and others a period of detention. I reminded myself that today’s youth get similar kicks from high speed car chases.

The overall tone of each section matches the period of the life. There is also a prevailing consistency throughout the book, including a healthy vulgarity (if at times disconcertingly graphic) which conveys something of the essential man beneath the changing periphery.

For writers in particular, the sections ‘New Directions 1951–64’ and ‘Sun Books and Russia’ provide a fascinating insight into a crucial period of development in Australian literature and of publishing in particular. Some may argue about the degree of influence Dutton claims for himself, yet he (with Max Harris,) must be given the credit for getting Australian Letters and the original Australian Book Review going, and (with Brian Stoner) for starting Sun Books. Others may find Dutton’s version of event at odds with the way they remember things. But then, as A.O.J. Cockshot, in The Art of Autobiography, says, ‘the autobiography has more power over the evidence than the responsible biographer’.

Yet I feel it is when recounting his experience as a biographer that Dutton is must compelling. One of the bonuses of writing biography is the need to visit the places where your subject has lived or spent time. Dutton’s search for the ‘real’ life of Edward John Eyre included being flown by his sister Chibs in her four-seater Cessna 172 over the Nullarbor Plain because ‘I had neither the time nor the stamina to walk like Eyre from Streaky Bay to Albany’. Fragments of lyrical description that mark such occasions offer some of the best writing in the book. Dutton’s research into Eyre’s life also took him to Leeds and London and finally to Jamaica where ‘many documents were rotting away’ and a page of the newspaper he was examining disintegrated in his hands.

One of the problems with autobiography is that the latter part of a life is still too close and there has not been the necessary distance from the events themselves to allow a proper perspective. Richard Coe (When the Grass was Taller) says that writing about childhood ‘enables a writer to do for part of his life that which he can never achieve for the whole of it: to see himself living through a complete experience in time ... ‘ Certainly the early chapters of Out in the Open have a quality of detachment and irony as well as a certain charm and completion. The last section of the book, while no doubt passionately sincere and a reflection of a changed life style, made me feel (to adapt Geoffrey Dutton’s words) that I was swimming in honey.

Comments powered by CComment