- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is Maurice French’s sixth work on the Darling Downs. An Associate Professor of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Southern Queensland, he is ideally placed to study this fertile plateau in south-east Queensland, reputedly the richest agricultural land in Australia.

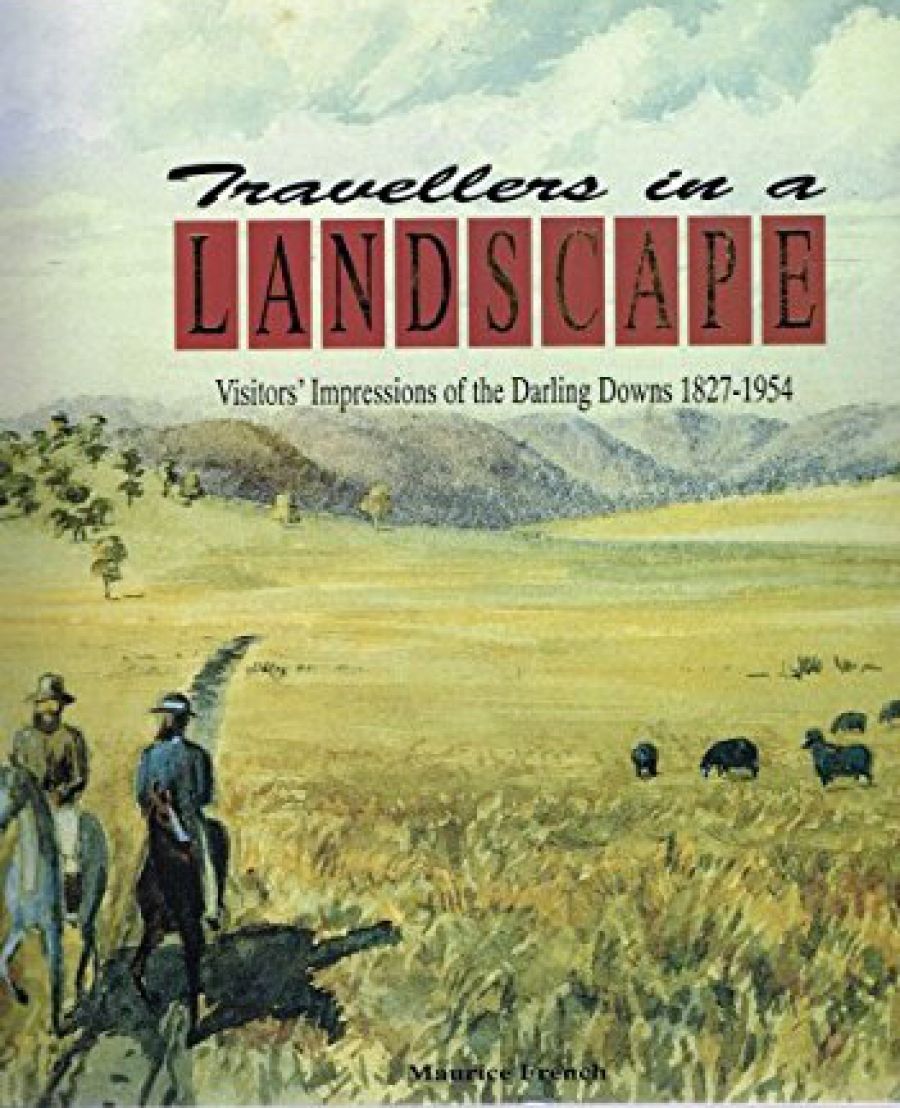

- Book 1 Title: Travellers in a Landscape

- Book 1 Subtitle: Visitors’ impressions of the Darling Downs 1827–1954

- Book 1 Biblio: USQ Press, $ 44.95 hb

Whatever his motive he presents a most valuable collection of excerpts from diaries, letters, and essays. They span the years 1827–1954, from white discovery of the Downs to its evolution from grazing to farming, to industry and the growth of an urban population in such centres as Toowoomba and Warwick. The early part is more interesting than that dealing with the later years.

There has been a plethora of histories of the Downs, ranging from H. S. Russell’s romanticised Genesis of Queensland to Duncan Waterson’s Squatters, Selectors and Storekeepers, which questions previously held favourable opinions on the character of our pioneers. French’s impressive trilogy – Conflict on the Condamine, A Pastoral Romance, and Pubs, Ploughs and ‘Peculiar People’ – continues the rewriting of history, establishing the now politically correct stance that our pioneers were in reality invaders, brutally dispossessing the Aborigines, ravaging and destroying the land, exploiting the workers, using corrupt political practices for personal gain. Most of our heroes, we are told, had feet of clay.

One of the exciting aspects of these travellers’ tales is the opportunity they give readers to make up their own minds about this piece of our history. Historians view the past through the distorting glass of the present. Burdened with hindsight and their prejudices, they are unable to see events of earlier years within the context of their times. These voyagers speak to us from the past as if it were today. Their stories ring true.

Most of the early writers, a number with university degrees, were products of a rigid English class structure, a Jane Austen-type life, with a tight environment, both physical and social. How they relished their adventures in this new land, even if it was full of discomfort and danger.

Thomas Archer, having crossed the Condamine in 1841, tells of ‘emerging on the glorious plains and open undulating ridges of the Darling Downs’. Daniel Bunce says in 1846, ‘our journey was over a country unequalled in any other part of Australia, either as regards beauty of scenery, variety of surface or the rich character of its grazing capabilities’.

‘There is a proud feeling of freedom,’ says Finney Eldershaw in 1842, ‘a strange delight … a wild pleasure which amply compensates for any loss of those easy luxuries of life which this species of adventure necessarily excludes.’

French categorises these early days as ‘The White Invasion’. Do these young men, bubbling with enthusiasm, staggered by the strangeness and vastness of the land, bear the hallmarks of invaders? Brutal, cruel, ruthless? Is French’s implied judgment fair?

In the chapter ‘Black Resistance 1843’, after his dangerous chance involvement in the bitter Battle of One Tree Hill, John Campbell concludes: And now upon the subject of the blackfellows I have no more to tell except that with all my hair-breadth escapes and risks among them I now in my old age have reason to thank God that I never pulled a trigger upon a blackfellow.

Robert Ramsey in his ‘Reflections on Frontier Conflict 1869’ discusses investigating as magistrate the murder by blacks of two Chinese shepherds, going on to say that, in respect of these murders, ‘the proper course for foreign intruders to pursue … is perhaps the most difficult and most serious question that a pioneer settler in this or any other country where he dispossesses the original inhabitants by force and occupies their territory has to consider.’ Others involved show similar sensitivity. Does this square with the now widely held belief that all our early settlers looked upon Aborigines as vermin to be summarily exterminated?

Undoubtedly, French will continue to amass and make available more such valuable material.

Comments powered by CComment