- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

These twenty-one stories have a pedigree; according to the customary list of acknowledgments, they have had a previous life littered across no fewer than twenty-six books, magazines, and journals, some of whose names are unfamiliar even to my local newsagent. I’m not sure these days if places of publication should properly be called ‘sites’, ‘topoi’, or ‘venues’. Such is the prevalence of dope in this book, however, that perhaps they could be called ‘joints’. But This Is For You is certainly greater than the sum of its parts.

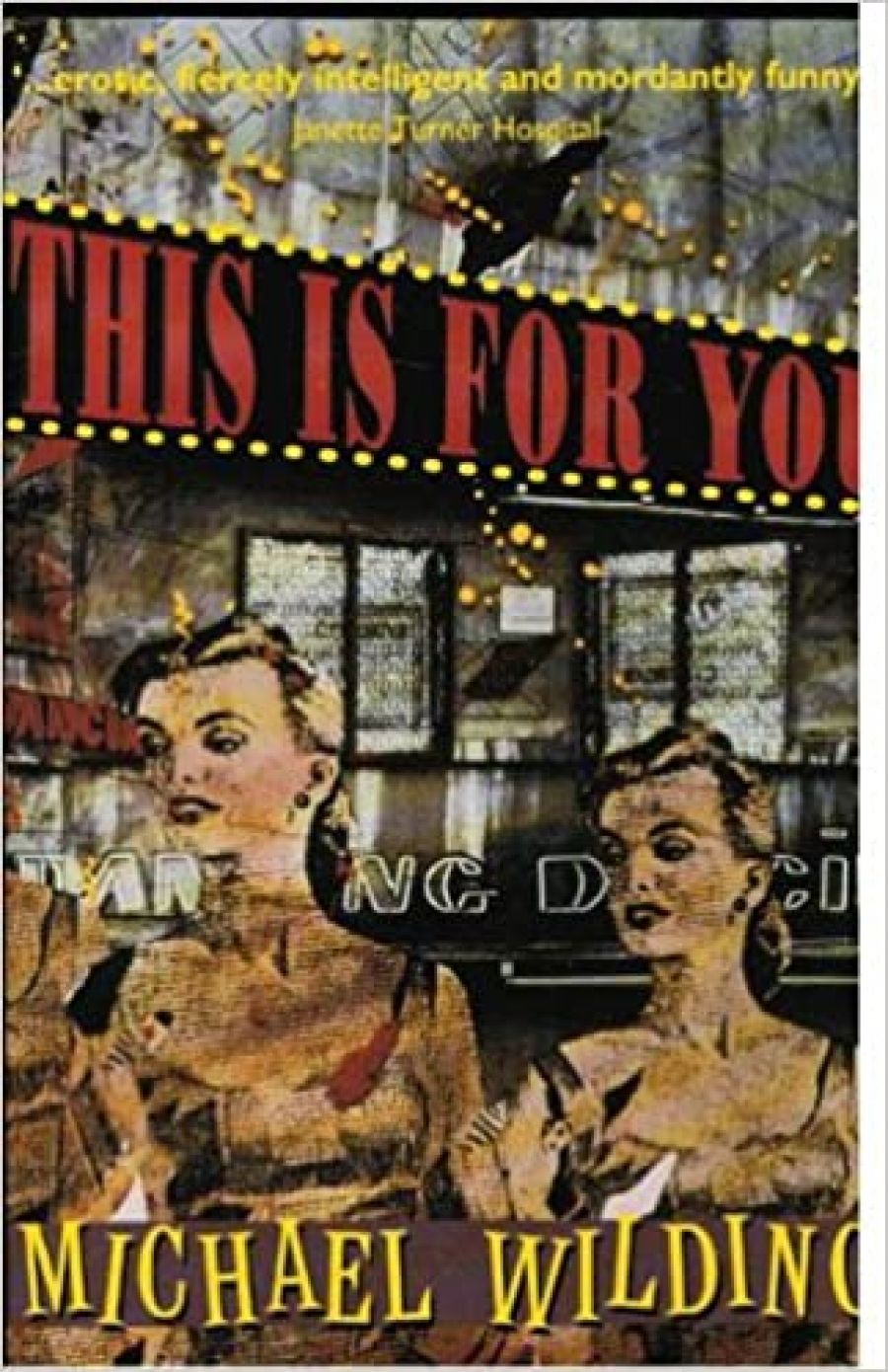

- Book 1 Title: This Is For You

- Book 1 Biblio: A&R, $16.95 pb

Characters who surface in one story seem to crop up again later on. I say ‘seem’ because there’s no guarantee that the Jon who appears in ‘NY 1969’ is the same Jon who appears in ‘The Beauties of Sydney’ after an evident lapse of time. But I hope so. The first Jon is a posturing revolutionary who smokes dope, gets arrested, and takes his visitors on a tour of the Big Apple’s sights. The second Jon, unmellowed by the passing of years, is nearly drowned by his hosts in Sydney, and provides another opportunity for Wilding’s wit: ‘these were the lifebelts you threw at drowning people and hit them on the head and knocked them unconscious so they could never reach out or hold on. I threw it cautiously and missed Jon by yards that he could not swim.’

Much of the humour in these stories is uncomfortable. It derides the aimlessness of the fey characters who people many of them. Take Marcus and Lydia. In a superb story called ‘Kayf’, they escape from London to North Africa and spend much of their time looking for the best deal on dope. Heading south on a train they meet a man whose skin is hardened where he kneels to pray and, having come to accept that ‘all good and true things now seemed faintly comic’, they are caught short. Wilding often ends on a note of such painful emptiness, in this case accentuated by the image of a submarine and guerillas on a desert beach. We find Marcus and Lydia again sharing a joint with bored academics, tripping in California, kept awake in a rooming house by a musician next door, getting drunk on the hospitality of a Russian family, and assuring them that life is ‘all conflict and difficulty and resentment’. We meet Marcus and Lydia over and over without much sense that they count for anything more than the spur of the moment. Wilding doesn’t waste much affection on these types. We are spared any kind of intimacy with them. He whittles away their pretensions before they lose themselves in a puff of smoke.

There are times, however, when passion flares in the writing. ‘Armistice’ bristles with the resentment a protester feels towards the way an aunt who was involved in a war effort imposes her values.

The final story, ‘I like him to write’, almost burns on the page. An academic has been working on the biography of a writer who spent twenty years in oblivion because of her political affiliations. The biographer approaches a younger writer who was both inspired and encouraged by her subject. The young writer believes that the biographer is doing no better than the investigations of the CIA fifty years earlier. It’s not too hard to pin real life names onto the personalities in this story, but that is the least of its fascinations. It works, I think, because of the levels of human vulnerability exposed. The subject is vulnerable to the biographer, the young writer craves the affirmation of the senior writer. She once said, ‘I like him to write’. He needed to hear it from someone.

Comments powered by CComment