- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dorothy Porter has been called an audacious poet. She has been called a sexy read. Doug Anderson described her as ‘One of our most exuberant and perceptive purveyors of passion.’ With the publication of her latest book, The Monkey’s Mask, Porter’s reputation stands firm.

- Book 1 Title: The Monkey’s Mask

- Book 1 Biblio: Hyland House S19.95pb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/0JQYgV

Porter changed publishers with this book, commenting with characteristic mettle: ‘I believed I had a unique book, a book that would require a unique publisher – a publisher with the vision to see a book of poetry going mainstream.’

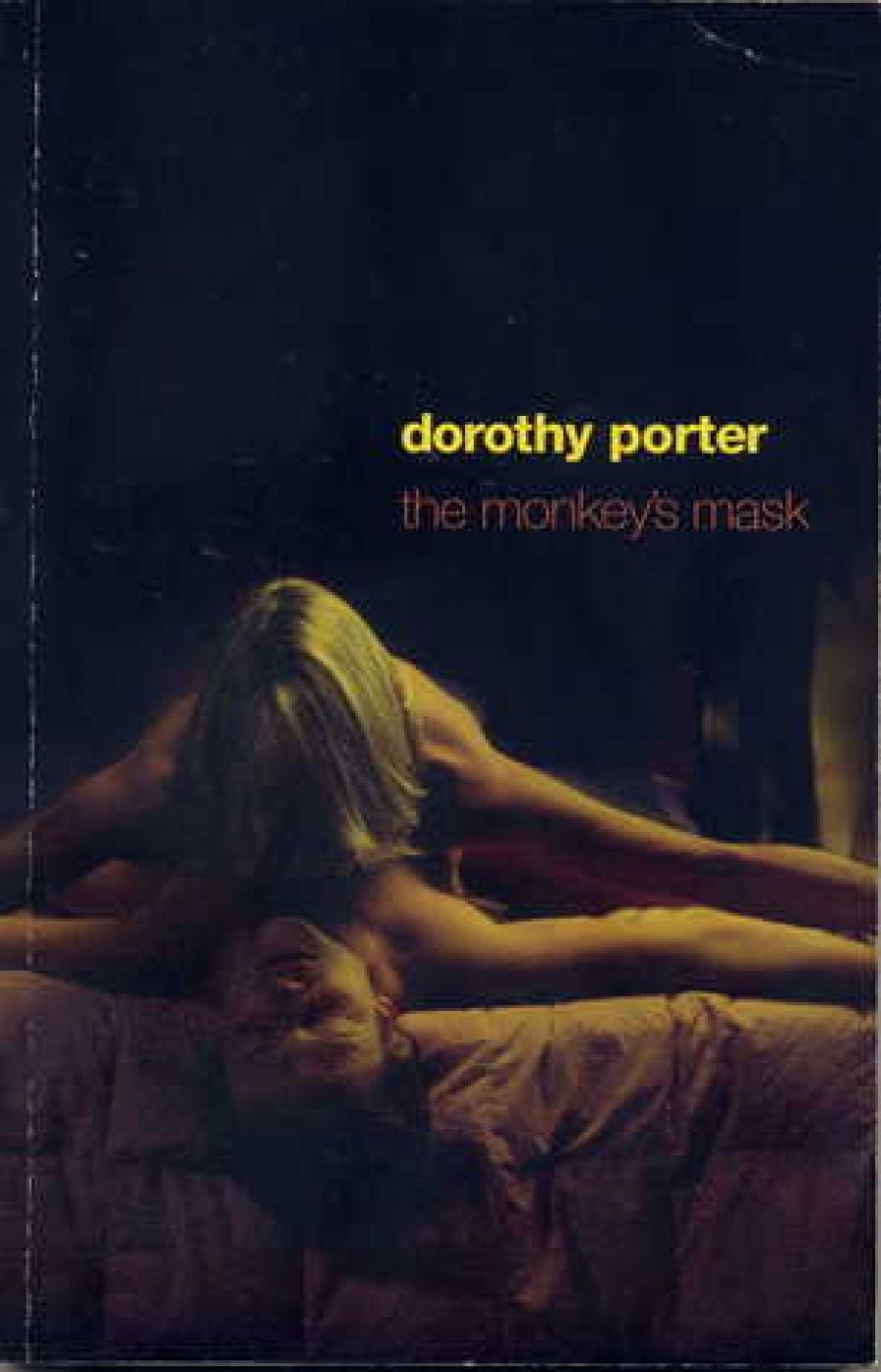

Hyland House have indeed produced a unique book. It is also a very beautiful-looking book. Vivienne Goodman’s cover design is sumptuous – that powerful, vulnerable neck will haunt you as you read; its resonance metaphorical, lyrical, physical, sexual – and sometimes all of these combined.

The Monkey’s Mask has all the ingredients of a good crime thriller interwoven with the stuff of lesbian romance – murder, mystery, suspense, tension, sexual frisson, and the classic femme fatale. And it’s all written in verse. ‘It’s where high art meets low life’, as it says on the blurb. It is also wonderfully playful and subversive as Porter has a satirical poke at the Sydney poetry scene.

The lesbian P.I. Jill Fitzpatrick, a wise-cracking, street-wise ex-cop living in the Blue Mountains. Porter gives a deft sketch of her main character:

I’m not tough,

droll or stoical.

I droop

after wine, sex

or intense conversation

…

I’m female

I get scared

Jill is employed to search for Mickey, a young university student and ‘special’ daughter of wealthy North Shore parents who has inexplicably disappeared leaving behind a pile of love poems. Not just the passionate gushings of a teenage girl but violent, sadomasochistic, pornographic pulp.

In her search for the missing girl Jill is inculcated into the heart of Sydney’s poetry scene – it is here that she will find the clues to Mickey’s disappearance. She is forced to attend poetry readings, which she find boring – ‘They’re only supposed to read / for fifteen minutes, / you’ll learn / Einstein’s Theory of Relativity / first hand, my dear / fifteen minutes can stretch / like an old rubber band.’ And in the name of duty rubs shoulders with two of Sydney’s most highly acclaimed male poets – the born-again Christian Bill McDonald and the suave modernist Tony Knight. All this gives Porter the opportunity to cock-a-snook at the pretentiousness of the male poetry establishment:

Bill calls light ‘dusky’

in every bloody poem

and he’s got a thing

about his grandfather’s hat

…

Come on, Bill,

that’s it, mate,

last fucking poem

I’ll be dead and burnt to ashes

before Bill’s dusky light sets

on his Grandad’s hat

Jill doesn’t read poetry, preferring thrillers herself, and she detests the whole poetry scene. And this is where Porter is at her satirical best because everything Jill says and feels and thinks and does is, of course, in verse. There is even a poem which has Jill pondering how a poem starts and one in which she contemplates writing one of her own – a sensation rapidly quashed. It is all good fun. (I was not surprised to find that the book is dedicated to Gwen Harwood, that consummate poetry prankster).

There are murders and betrayals and red herrings and a number of nefarious characters and the plot races a lung at break-neck speed as the words race down the page. Porter’s language is lean, colloquial, raw, yet rich in imagery and that sensuousness for which she is renowned.

The central thread is the lesbian romance between Jill and Mickey’s university lecturer, the seductive, duplicitous Diana. It’s an incongruous and fraught relationship and elicits much of the humour in the book: ‘In love I’ve got no style / my heart is decked out / in bright pink tracksuit pants / it weaves its huge bummed way / through the tables to Diana’. But it is also the site of Porter’s most sensual writing:

…

she lets her breasts free

they fall in my hands

her nipples grow

between my lips

she strokes my hair

‘Jill’

my name in her mouth

my eyes close

in the musk and silk

of her belly

her thighs

under my nose

the sweetness of her

as she shudders

on my mouth

Female sexuality is graphic, palpable, but still sensitively suggestive in its evocation of smell, taste and touch. Rosie Scott has said that as a novelist she has found the English language ‘surprisingly barren when it comes to terms for the body, sexual emotions and processes.’ There just aren’t the right words. This doesn’t appear to be a problem for poets. Certainly not for Dorothy Porter. Perhaps it is because of poetry’s use of image, simile and metaphor, as Jan Owen suggests, and also because it appeals to the senses and allows, as readers, to enter the poem and take part in the sensation.

There is much to commend this book. One little quibble. I felt the ending was less than satisfying – I obviously can’t say much without revealing too much – but I felt the need for stronger retribution and justice.

The Monkey’s Mask is a daring venture. It has of course two margins from which to emerge. As a lesbian narrative it should swim along comfortably with the likes of the current mainstream lesbian film Go Fish which has a broad appeal to audiences of all sexualities. But how will a book of verse fare out there alongside fiction? There is a scene (a little poem entitled ‘My throat’) in which Diana licks the length of Jill’s neck and runs her fingers down her wind-pipe:

‘your throat’

she says

‘is state of the art’

Is The Monkey’s Mask state of the art poetry – this book which transgresses boundaries between poetry and fiction, which makes poetry accessible, readable, exciting? Let’s hope that it wins a few gold medals out there in the mainstream.

Comments powered by CComment