- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Feminism

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Volatile Bodies is an important book: its challenge is nothing less than the development of a non-essentialist, feminist philosophy of the body.

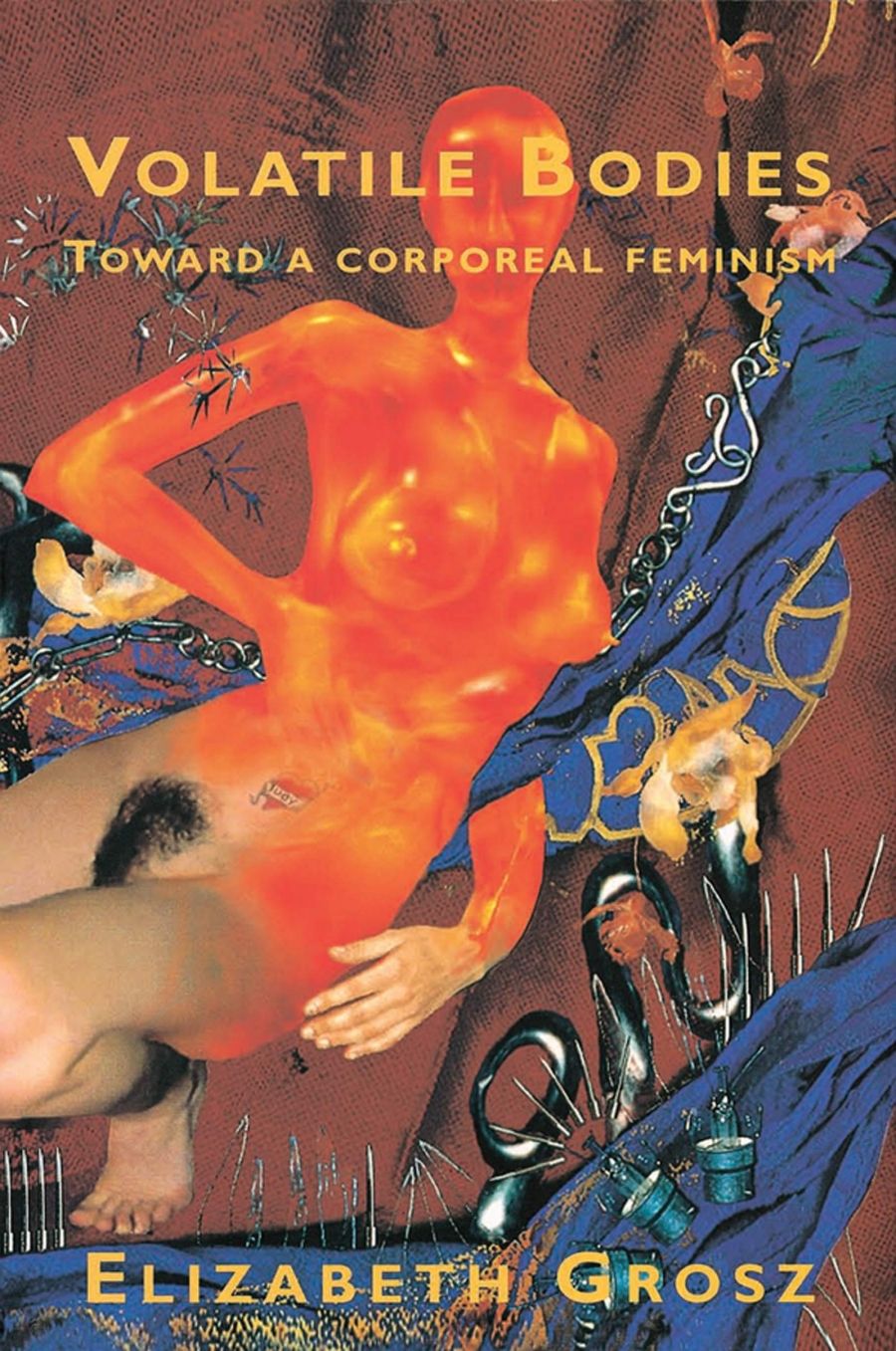

- Book 1 Title: Volatile Bodies

- Book 1 Subtitle: Towards a corporeal feminism

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.95

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://booktopia.kh4ffx.net/DV0LYn

Grosz argues that a mind–body dualism is implicit in how we have understood bodies and corporeality on the one hand, and systems of thought such as knowledge, reason, subjectivity, and interiority, on the other. Her book is about how we might subvert the traditional superiority of the mind in order to open up new possibilities of thought. By toppling the mind-body dualism, we can rethink bodies in terms other than those proposed by existing frameworks of psychology, psychoanalysis, and phenomenology, since those frameworks are themselves conceived in terms which privilege the mind over the body.

We can also rethink knowledge, reason, subjectivity, and interiority. ‘Bodies,’ states Grosz, ‘have all the explanatory powers of minds’, and so it makes sense to reconsider systems of thought in terms of the body instead of just the mind. The proposal is an exciting one, but my major criticism is that Grosz doesn’t always make clear or strong enough linkages between her thesis and the areas of thought she examines. Fortunately, the reservation doesn’t detract from the power of the project; rather, it means that the work that should flow from the beginning she has made will have to explore and consolidate those linkages early on.

The context of the book is arranged according to the model of the Mobius strip, used by Lacan in discussing the subject. The Mobius strip twists a two-dimensional single continuum to form a three-dimensional figure eight. Grosz uses the model to avoid a straight inversion of the mind-body dualism and to avoid implying any simple causality. For her this model

also provides a way of problematizing and rethinking the relations between the inside and the outside of the subject, its psychical interior and its corporeal exterior, by showing not their fundamental identity or reducibility but the torsion of the one into the other, the passage, vector, or uncontrollable drift of the inside into the outside and the outside into the inside.

After Grosz’s initial contextualising section in Part I, Part II, ‘The Inside Out’, examines selected works of Freud, Lacan, and Merleau Ponty to look at how ‘the subject’s corporeal exterior is psychically represented and lived by the subject’. Part III, ‘The Outside In’, uses the reverse mode, from body to mind, focusing on the works of Nietzsche, Foucault, and Deleuze and Guatteri. Part IV moves away from male theorists and their view of ‘the’ body to look at the ways of thinking about sexual difference, primarily through the work of Mary Douglas and Julia Kristeva.

Grosz anticipates feminist criticism – she suggests almost ostracisation – not so much of her arguments, but of her material. ‘The product of passion and intense fascination, (this book) has also been fuelled by the energy of profound theoretical insecurity and the full awareness that I have skated along the brink of a theoretical precipice overhanging extreme political isolation.’

In response to the anticipated objection to her extensive use of male theorists, Grosz takes the obvious and defensible response that it is better to reclaim than abandon the land. She similarly counters possible criticisms of her very subject matter, the body: the project concentrates on the body ‘in order to contest (essentialist, ahistorical or universalist) terms, to wrest a concept of the body away from these perils’. The other danger, linking women’s ‘subjectivities and social positions to the specificities of their bodies’ is similarly dealt with. The dangers are as clear as the justifications are sound, but what is less clear is the reason for the slightly heavy weather Grosz makes of them. Perhaps she could have been even more bold and used the opportunity to throw down the mantle to her readers to take her experiment in developing a corporeal feminism to the next stage.

The power of individual chapters, in terms of articulating a new way to think about bodies and about epistemological and ontological systems, is uneven. Throughout, Grosz maintains the standard of lucid explication of complex, dense theories for which she is so highly regarded. The first chapter, ‘Refiguring Bodies’, uses lively and succinct critiques of dualism, monism, and various feminisms to set up the parameters for a feminist philosophy of the body. However, the linkages between detailed readings and the overall frame need to be integrated more closely in some other chapters. It is not always clear, for example, where the discussions about psychoanalytic, neurological, and phenomenological constitutions of the body lead.

The criticism is not true of the chapter which focuses on explorations of becoming and transformation in Deleuze and Guatteri. Here, Grosz is explicit about her selective use of male theorists to develop and experiment with theories that might prove useful for her project. In being equally explicit about the advantages and drawbacks of a Deleuzian framework, she succeeds is positing a clear strategy and starting points for what to take away in developing a feminist philosophy of the body. It will be interesting to see how the challenge is taken up.

Comments powered by CComment