- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

These are the opening lines of Wishbone. Already I know that this is a book I want to continue reading, and not just for the promise of sex, romance, and intrigue. I am also attracted by the ‘difficulty’ of knowing just what tone is being taken here, and just who is speaking to me in these words. As well as being thrown immediately into the story, the reader is confronted with this tone – analytic, cool, amused? There is the holding-back of both information and conclusions. There is the emphasis on bodies, their awkwardness, the space they take up, their economics … and later the words and wishes they produce. Knight will say to his lover, Emmanuelle, ‘I thought we could have an affair and just be bodies.’

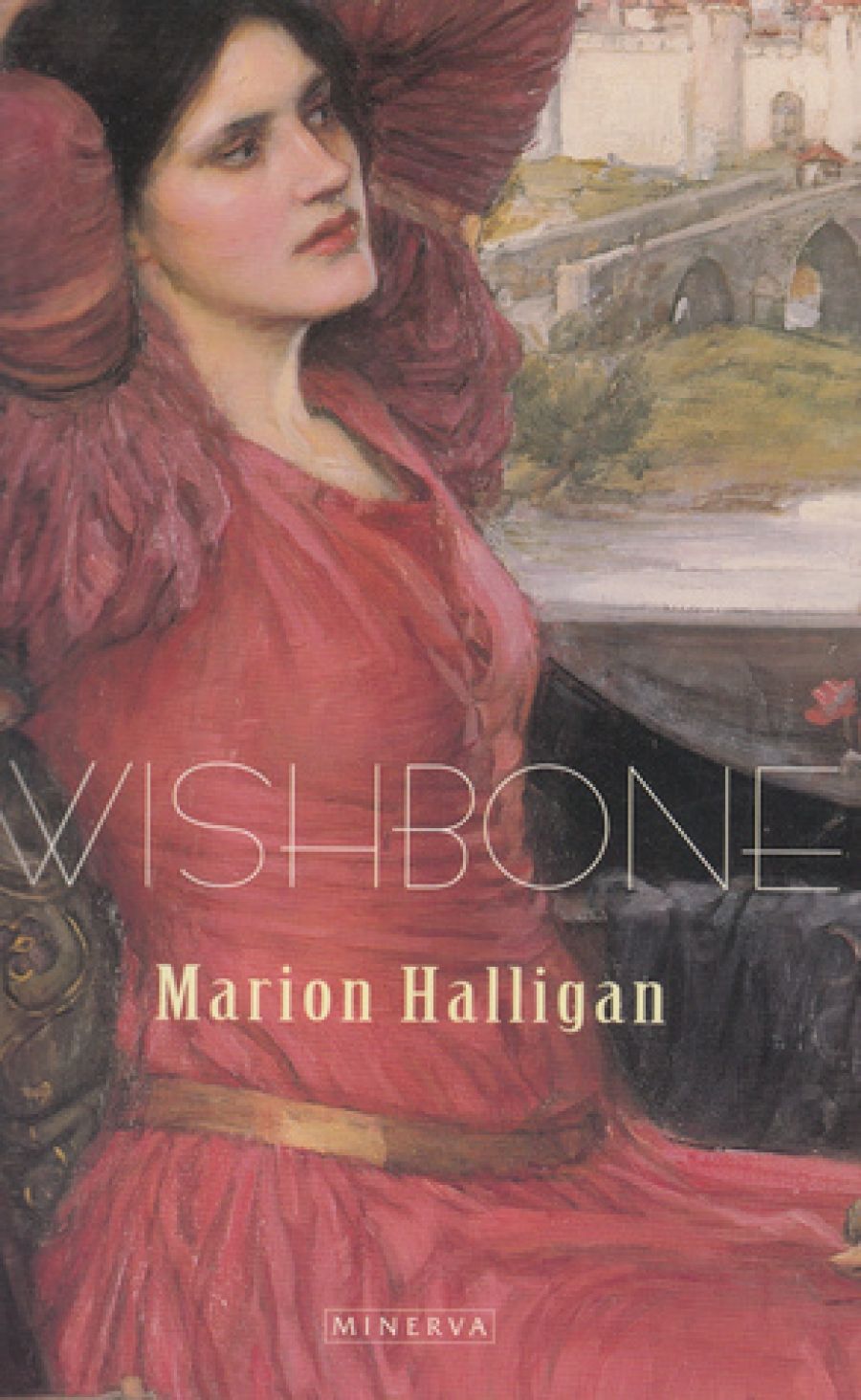

- Book 1 Title: Wishbone

In Wishbone there are always more than several things happening. From the moment of its title the book is ‘split in its focus between the world of material, bony objects and that other world of fantasies and wishes which exists mainly (only?) in stories. As a book of objects it is set among people who in a scaled-down version of Melrose Place, with the heated outdoor swimming pool as the centrepiece, a body-building gym as a sideshow, and sexual longings, misunderstandings and unexpected couplings galore. We learn of the role of essential oils in massage and frottage, we wait for Emmanuelle to decide whether she will deliberately smash a Meissen vase. We watch the way she desires and possesses an Aboriginal painting of the Wandjina spirit. There is the exquisite hundred-year-old kitchen with its copper sink to protect the glow of delicate china. And food:

There was a boned fowl stuffed with pistachio nuts and ham and chicken mince, grilled peppers loaded with garlic, quail split and marinating in thyme and juniper berries, a bowl of tiny potatoes to eat hot with aioli and celery and radishes, slices of raw cured tuna with sweet onion and dill and horseradish, frangipani tarts with sliced pears in precise glazed patterns, smelly Milawa cheeses and walnut bread …

The words become more than the meal. Though the women and the men come with their material bodies which need dressing, undressing, feeding or starving, they come also with a sense of themselves as characters in stories: ‘Wearing these clothes in this room is a performance, the sense of which must never be lost.’ After all, with names such as Knight, Lance, Emmanuelle, they don’t merely exist, they symbolise. Those wishing-tales of the fisherman’s wife and the three wasted wishes of the black pudding are never far away, along with Grimm’s transformation story of Rose Red and Snow White. The fun here is that, as in the fairy tales, wishes do come true, in ways that could not have been imagined. Instead of bears turning into princes, accountants become lovers, prudes become smooth-muscled lovers, computer millionaires are exposed as mere front men for the brilliance of their secretaries, a murder is achieved with gusto, luck, and a kind of innocence for the killer.

The outcomes of the wishes are in the end kinder to the women than to the men. In this the novel is perhaps sentimentally true to its contemporary politics, or openly treating itself to a fantasy of just desserts, or perhaps letting us know that this is how it would be for men if women could, at last, wish their way out of the present. It is, like many fairy tales, a wicked book. The men are condemned to their difficult fates: marriage, dutiful fatherhood, deceit, celibacy, befuddlement, death. The women are released into the possibility of dangerous choices, or unexpected freedom and wealth, into a sense of identity and purpose, even to a position of power in the business world.

In its adult, sexual, political play with traditional children’s stories, the novel has affinities with the writing of Margaret Atwood and Angela Carter. ln the way the novel focuses on details of women’s lives and conversations, the way it takes place in kitchens, gardens, dining rooms, antique shops, and bedrooms, it has affinities with the books of Helen Garner and Andrea Goldsmith, and shares with the work of those writers a richness, liveliness, immediacy, and sense of truthfulness. It joins with Virginia Woolf in pursuing a project of transformation which is altering forever what we find, what we look for, and what we value in books. Sixty-five years ago, Woolf wrote:

Speaking crudely, football and sport are ‘important’: the worship of fashion, the buying of clothes ‘trivial’ … This is an important book the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing room. A scene in a battlefield is more important than a scene in a shop …

Wishbone belongs to a strong tradition of writing about women’s lives, while it is also writing about the ways women’s lives are written.

Like all the best books it is a book that loves books. It can’t resist quoting from Milton, or from the Bible, or showing us how Dickens can give us details of the ways people once lived. Emmanuelle makes a room of her own and stocks it with books. Not only objects are treated in loving detail, but words are delivered to the reader like small, luminous ornaments taken from a bookshelf and handled briefly: ‘The sky was nacreous as a pearl shell promising something out of irritation.’

From Wishbone by Marion Halligan (WHA):

She learned that believing you can’t bear something doesn’t mean anything. She stood on the platform of the underground railway and heard the boom of the train in the tunnel, felt the concussion of air it pushed out. Three steps forward at the right moment … Every afternoon this release offered itself. Every afternoon she rehearsed it, the three steps forward at the right moment, not too soon, not too late, the timing not overly precise, a little leeway either way. In her head she did this, but her feet never moved. Nor did she say, tomorrow I’ll really do it, she simply stood, each afternoon in her head taking the three steps, her feet not moving, and once when a man running down the stairs stumbled and fell against her she felt the anger of fear: he could have pushed her under a train. After a while she stopped thinking I cannot bear it; she realised she had borne it. The impossible loss, and yet there she was, not stepping, never stepping, under the saving train. Or off a bridge, or swallowing pills, except they had never been an intention, the train was always her solution.

She still thought of Brian with pain but not all that often. The winter had come. Too cold for cliff faces. He’d gone to a job in Perth, a senior lectureship. His wife had gone with him. She compared other men who took her out with Brian and they never measured up, but then she met Lance Latimer. He didn’t measure up either at first but after a while she stopped making comparisons. Lance’s real name was Lancelot, which he kept a secret, along with two other given names and the first part of a hyphenated surname, but he trusted all of them to Emmanuelle and shortly afterwards they got engaged, and then married, in a grey stone church that his family always called ours, just like a church in an English village said her parents.

Comments powered by CComment